This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

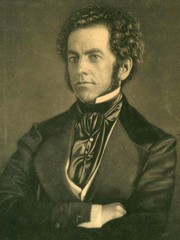

Thomas Dent Mutter was born on March 9, 1811, in Richmond, VA. His mother died in 1813, and his father died of tuberculosis in 1817. Thomas was orphaned when he was barely 8 years old. His father left him a somewhat meager inheritance and in his early life had to do with less that others with his objectives in life. He was well educated under the tutelage of Robert Carter, his guardian, and in 1824 he started his studies at the Hampden Sidney College of Virginia. He continued with a medical apprenticeship with a Dr. Simms in VA. He was well respected and even at his early age he would do home visits for his medical benefactor with great results. He started medical studies at the University of Pennsylvania, where he earned his MD in 1831. The new young doctor, Thomas Dent Mutter, MD was only 20 years of age.

At the time, Europe was the place to go to if you wanted advanced medical studies. Dr. Mutter had no money, so he applied as a ship surgeon to be able to cross the Atlantic. Once in Europe, he spent time in Paris, where he studied under the tutelage of Dr. Guillaume Dupuytren. He later studied for a short time in England where he met Dr. Robert Liston. Following Dupuytren's teachings, Mutter was fascinated by plastic surgery.

A chance encounter with what was to become his first well-known acquisition of a medical curiosity, Mutter started thinking on how to help those people that were known at that time as “monsters”, patients who the general public did not see, because they did not appear in public. The curiosity in question was a wax reproduction of the face of a French woman who had a “horn” arising from her forehead. This piece is on exhibit at the Mütter Museum.

Back in the United States in 1832, Thomas Dent Mutter changed his last name to give it a more “European” sound and added an “umlaut”, so now he was Thomas D. Mütter, MD. It may also be that he wanted to pay homage to his Scottish-German heritage, who knows? He opened his medical office in Philadelphia and although it took time, eventually he had a thriving practice. One of his specialties was the work on “deformities” so common at the time because of facial scars born out of the use of open fires in houses, and deformities caused by burns and loss of tissue due to chemicals used in local industry. Dr. Mütter is the pioneer of what we call today “Reconstructive Surgery”.

In 1835 he was asked to join the Medical Institute of Philadelphia as an assistant professor of Surgery. He was an instant success. Dr. Mütter was adored by his students because, he would question the students and guide them to discovery instead of just lecturing and leaving. In his Discourse eulogy of Dr. Mütter by Joseph Pancoast he writes:” The power of attracting students near him by his mingled gentleness, energy, and enthusiasm; of fixing their attention by the lucid and methodical arrangements of his Subject, by his clear demonstrations, and sprightly oral elucidations, came so readily to him, and was so early displayed) as to seem almost intuitive.” In 1841 Dr Mütter was appointed Professor of Surgery at the Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia.

Dr. Mütter had always had poor health, even in childhood, and his dedication to his passion, long hours, took its toll on his body.

In 1956 he set sail for Europe and resigned his teaching duties. He was named Emeritus Professor of Surgery. Unfortunately, the trip did not help, and he returned to the US in early 1958. Fearful of another winter in cold Philadelphia, he moved to Charleston, SC, where he died on March 19, 1859.

Dr. Mütter’s story does not end here. He was an avid collector and throughout his short life he had pulled together an impressive collection of medical oddities, samples, and curiosities. Knowing that his life was at an end, he negotiated with the Philadelphia College of Physicians to have them host his collection in perpetuity as well as the creation of a trust fund that would ensure that the public and medical students would have access to this incredible collection. Through the years this collection has increased and is known today as the Mütter Museum of the Philadelphia College of Physicians. I strongly urge our readers to visit this incredible museum. For more information, click here.

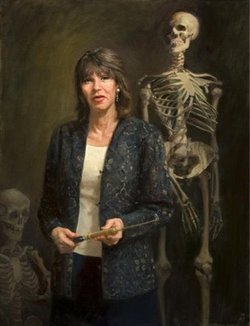

Personal notes: In the late 90’s, I attended a meeting of the American Association of Clinical Anatomists. During the meeting I met Gretchen Worden, who at the time was the Curator of the Mütter museum. Gretchen was inspirational, fun, and a great conversationalist! I had the opportunity to visit Gretchen at the Mütter museum and had the luck to be treated to a “behind the scenes” tour. What an experience! I was saddened to hear that Gretchen Worden passed on August 2, 2004. Still, in my recent visit to the Mütter Museum, I was glad to see a new section at the museum that remembers Gretchen. Her biography can be read here.

I would like to thank Dr. Leslie Wolf for lending me the book by O’Keefe that lead to me writing this article. Dr. Miranda

Sources:

1. “Dr. Mütter’s Marvels: A True Tale of Intrigue and Innovation at the Dawn of Modern Medicine” O’Keefe, C. 2015 Penguin Random House, LLC

2. “A Discourse Commemorative of the Late Professor T.D. Mütter” Pancoast, J. 1859 J Wilson Publisher

3. “Thomas Dent Mütter: the humble narrative of a surgeon, teacher, and curious collector” Baker, J, et al. The American Surgeon, Atlanta 77:iss5 662-14

4. “Thomas Dent Mutter, MD: early reparative surgeon” Harris, ES; Morgan, RF. Ann Plast Surg 1994 33(3):333-8 5.

5 "Things I Learned from Thomas Dent Mütter” O’Keefe C.

All images with permission from The Mutter Museum.

IN MEMORIAM