Text from the presentation at the 2014 Vesalius Continuum Meeting in Zakyhnthos, Greece by Pavlos Plessas.

Continued from: Powerful indications that Vesalius died from scurvy (3)

Metellus mentioned another witness during Boucherus’ narration of their terrifying journey and Vesalius’ end. With him was his friend Johannes Echtius, an esteemed physician. Echtius was one of only a handful of doctors who had studied this new deadly disease, scurvy, and the very first person to write a treatise on it . In that treatise he had given the illness a name: scorbutus.

It is hard not to feel that this meeting between Echtius and Boucherus was not by chance, but, since nothing is known about it, any hypothesis made, however reasonable, will remain no more than a supposition.

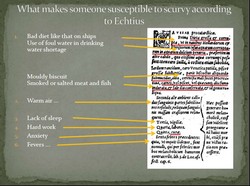

Fortunately, Echtius’ presence in that meeting gives us the opportunity to discern, through his friend’s letters, whether the 16th century expert believed that scurvy was Vesalius’ cause of death. Echtius had identified six conditions that made someone susceptible to scurvy, which he believed was contagious. The first was gross and corrupt diet, like the one on board ships, and the use of corrupt water in conditions of clean water shortage. The remaining five could all lead to scurvy independently, even if the diet had been good, because they generated an excess of melancholic humour, which in his opinion was the cause of the disease. As number five he had listed worrying.

It is easy to see what Metellus was pointing at when he accused Vesalius of having failed to provide adequately for himself. Pilgrims used to take with them their own supplies to complement the ship’s often unpalatable food. Echtius and Metellus believed that the ship’s food put Vesalius in danger of scurvy and he failed to take enough of his own. The subsequent shortages made things worse and, additionally, forced Vesalius to resort to drinking stale and foul water. His extreme worrying, after the disease appeared in others, made it almost inevitable that he too would contract scurvy. His sudden collapse and death did not come as a surprise either since this frequent scorbutic outcome is mentioned in Echtius’ treatise .

By expressing his conviction about the reasons that led to Vesalius’ death Metellus shows that he must have held a firm opinion on which precisely disease had killed him. Yet, incredibly, he fails in both his letters to name it expressly. Again, only scurvy can convincingly explain this failure. Echtius had written his treatise on scurvy in 1541 in the form of a letter , which for a long time had remained unknown even to some of the few doctors that had shown a keen interest in the disease. The treatise was not published until 1564, the year Vesalius died, in a book by Balduinus Ronsseus , and even then it was wrongly attributed to Johannes Wierus, who had sent it to Ronsseus. This error was only possible because Ronsseus, although he had been interested in scurvy for at least a decade , had not until then become aware of it. Consequently he had probably never come across the name scorbutus either. When the doctors of that time did not confuse scurvy with St Anthony’s fire, icterus niger, syphilis or leprosy, those who had a vague idea what they were dealing with, called it magni lienes, or stomacace and sceletyrbe. It would have been pointless for Metellus to inform his correspondents, a publisher and a theologian, that Vesalius had died from an illness Echtius called scorbutus when the word was meaningless even to well informed physicians.

Echtius may have been the world authority on scurvy but there were aspects of Boucherus’ story he must have found puzzling. The disease had broken out in the Mediterranean, an area that was believed to be free of scurvy. The diet of the crew had been bad, they worked hard and often spent the night sleepless – numbers 1, 3 and 4 respectively in his list of preliminary causes of scurvy – yet they did not get infected. Scorbutic Nostalgia remained unobserved for another two centuries, so Vesalius’ weird behaviour must have also caused him to wonder. Echtius then, along with Metellus, could not have invented this story, simply because they were unable to see that everything in it actually made sense. Neither could Boucherus have made up the story, because he knew much less about scurvy, if he knew anything at all. The probability that the events had been invented and put together randomly is absolutely negligible, given their perfect correlation with conditions that favoured an outbreak of scurvy, the timing of the outbreak, and the described symptoms; more so if all these are combined with the story having been afterwards presented to the planet’s most experienced scurvy expert.

Therefore, it is suggested that Metellus’ letters give a true account of Vesalius’ last days, and, simultaneously, that Vesalius, suffering from scurvy and seriously affected by scorbutic Nostalgia, managed to reach the southern part of the mythical kingdom of Odysseus – the land foremost associated with nostalgia since the dawn of history – and deposited there his own lifeless body.

Initial page of this article here.

Personal note: My sincere thanks to Pavlos Plessas for contributing this article to "Medical Terminology Daily". His theory and the evidence he presents is compelling, and although not proven, a powerful case is made for the cause of Vesalius' death at the gates of the port of Zakynthos, Greece. The fate and lost location of the illustrious anatomist's body is also researched in another article in this blog. I am proud to have been one of the many international attendees to the 2014 meeting in the island of Zakynthos. Dr. Miranda.

UPDATE: The case made by Pavlos Plessas is compelling, robust, and makes sense. Still, there are others that do not agree to his position, creating a discussion on the subject. In 2017, three years after his presentation in Zakynthos, Theo Dirix and Dr. Rudi Coninx published the article "Did Andreas Vesalius really die from scurvy?" which you can read here.

Sources and author's comments:

27. De Scorbuto, vel Scorbutica passione Epitome in 1541.

28. “… aliquoties vero desinit subito, ac mortali deliquio animi”.

29. The letter was addressed to a Dr Blienburchius of Utrecht. See Petrus Forestus, Observationum et Curationum Medicinalium, Tomus Secundus, Libri decem posteriores, Rouen 1553, p. 419.

30. De magnis Hippocratis Lienibus Libellus, Antwerp 1564, pp. 26a – 31b.

31. See De magnis lienibus Hippocratis, Plinique stomacace seu sceletryrbe epistola of 1555 in page 152 of Ronsseus’ De hominis primordiis hystericisque affectibus centones, published in 1559. I am indebted to Theodoor Goddeeris for pointing this out.