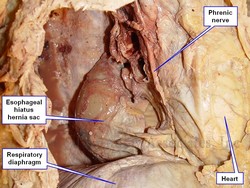

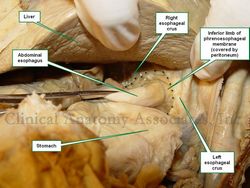

Esophageal hiatus hernia in situ.

The arrow points to stomach and greater

omentum herniating into the thorax

UPDATED: An esophageal hiatus hernia (also known as a hiatal hernia) is caused by a dilation of the esophageal hiatus and its component structures, the phrenoesophageal membranes (ligaments).

Since the intraabdominal pressure is higher than the intrathoracic pressure, abdominal contents -usually stomach and greater omentum- can herniate through the dilated esophageal hiatus into the mediastinum, the central region of the thoracic cavity. This presents as a hernia sac whose walls are formed by endothoracic fascia, phrenoesophageal membranes and parietal peritoneum.

There are two main types of esophageal hiatus hernias. Type I is known as a "sliding hiatal hernia" and is characterized by a complete ascension of the esophagogastric junction and abdominal esophagus into the thoracic hernia sac. This is usually accompanied by a typical "hourglass image" in a radiographic assessment, and also presents with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Type I esophageal hiatus hernias are more common.

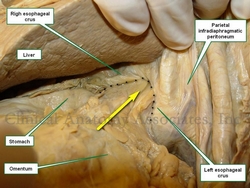

Esophageal hiatus hernia, reduced.

The dotted line shows the edge of

the enlarged esophageal hiatus

Type II esophageal hiatus hernia is known as a "paraesophageal hernia" and represent about 5 - 15% of esophageal hiatus hernias. In this case, the esophagogastric junction maintains its anatomical position inferior to the respiratory diaphragm, but the fundus and body of the stomach, along with some greater omentum herniate alongside the esophagus into the mediastinal region of the thoracic cavity. Although there can be GERD, this type of hernia usually presents with little symptomatology, and when it does, symptoms are related to ischemia or partial to complete obstruction. There are variations of type II hernia, which are classified as Type III and IV. Type IV, although rare, will include other viscera in the hernia sac, including colon, spleen, or even small intestine.

The accompanying images above depict a Type I esophageal hiatus hernia. The superior image shows the hernia in situ where the stomach and greater omentum are still in the hernia sac. The inferior image shows the contents reduced and the abdominal esophagus being pulled into the abdominal cavity. The dotted line shows the dilated esophageal hiatus that needs to be repaired to prevent recurrence of the pathology.

Click on this link for additional information on esophageal hiatus hernia surgery.

The image below answers a question by Victoria Guy Ratcliffe, who asked via Facebook "What would it be if it feels like you've got a blockage right at the level of the heart? That's too high for a hiatal hernia, isn't it?" The image answers the question. It shows a dissection of the left side of the thorax. The anterior thoracic wall and the left lung have been removed. The heart is immediately superior and anterior to the esophageal hiatus, and the hernia sac of a Type I esophageal hiatus hernia is seen immediately posterior and in contact with the heart. Whether this means that you will "feel" the hernia, it is up for debate, as all these structures have visceral innervation. Most probably, a well-developed Type II esophageal hiatus hernia might interfere with swallowing at this level, causing the sensation she mentions. Thanks for the question, Tori.

For additional information:

"Approaches to the Diagnosis and Grading of Hiatal Hernia" Kahrilas et al Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008 ; 22(4): 601–616.