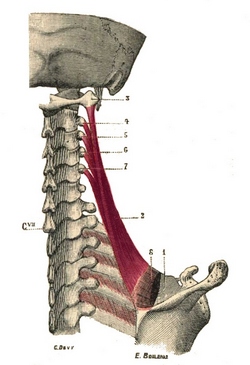

The levator scapulæ muscle (levator anguli scapulæ) is a triangular multipennate muscle which extends between the cervical spine and the scapula. This muscle is deep to the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscle.

It is formed by discrete muscular slips that originate from the first four transverse processes (C1-C4). It can have an extra slip from C5 (as shown in the side image).

These muscular slips pass posteroinferiorly, joining, and inserting in the superior scapular angle and the scapular medial border between the superior scapular angle and the medial origin of the scapular spine. It may attach to the scapular spine.

There are other anatomical variations including muscular slips that may extend to the occipital bone or mastoid process, to the trapezius, scalene, or serratus anterior magnus muscles, or to the first or second rib.

It receives nerve supply from the fourth and fifth cervical nerves and by a branch from the dorsal scapular nerve. The dorsal scapular nerve arises from the C5 root of the brachial plexus.

It receives its blood supply from the dorsal scapular artery.

The function of this muscle depends on which bony element is fixed, the scapula or the cervical spine. When the spine is fixed, the levator scapulae elevates the scapula and pulls the superior portion of the medial scapular border superomedially. When only one scapula is fixed, the head and neck flexes and rotates ipsilaterally while it extends the neck contralaterally.

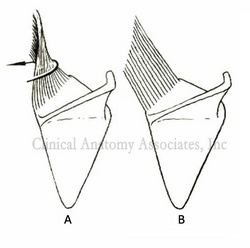

The order and shape of the muscular slips is interesting, as the slip from the transverse process of the Atlas (C1) twists posteriorly and descends to insert as the most posterior and inferior fibers in the medial border of the scapula. The other slips follow a similar pattern, which is what allows this muscle to rotate the neck. This indicates that the fibers of the levator scapulae muscle are spiral and the fibers follow the contour of the neck. This makes (to my knowledge) the levator scapulae the only spiral muscle of the body. This is shown as "A" in the second side image; "B" represents the misconception on the direction of the fibers in this muscle.

Since it is a common sign of stress and bad posture to raise the shoulders, this muscle can spasm, causing neck pain and in some cases be a trigger for headaches.

The Levator scapulæ is one of the 17 muscles that attach to the scapula.

Note: The first side image shown in this article is from “Gray’s Anatomy” (1918) which is in the public domain. The second side image is from Arnold’s “Reconstructive Anatomy” (1968).

Note: Animated image below by Wikimedia Commons - Anatomography [CC BY-SA 2.1 jp (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.1/jp/deed.en)]

![Anatomography [CC BY-SA 2.1 jp (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.1/jp/deed.en)]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a1/Levator_scapulae_muscle_animation_small2.gif)

Sources:

1. “Gray’s Anatomy” Henry Gray, 1918 2. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8th Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

2. "Tratado de Anatomía Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8th Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

3. "Gray's Anatomy" 38th British Ed. Churchill Livingstone 1995

4. “An Illustrated Atlas of the Skeletal Muscles” Bowden, B. 4th Ed. Morton Publishing. 2015

5. “Reconstructive Anatomy, A Method for the Study of Human Structure” Arnold, M. W.B. Saunders. 1968“Gray’s Anatomy” Henry Gray, 1918