By Maurits Biesbrouck, MD. Continued from "Andreas Vesalius’s fatal voyage to Jerusalem (4)".

For the first page of this article, click here.

The story by Solenander

An interesting story, told by Reiner Solenander (1524-1601), deserves our attention here (12). His report is important, but it was hard to find, because it is included in a work of Thomas Theodor Crusius, namely his Vergnügung müssiger Stunden, from 1722. Dr. Theodoor Goddeeris found a copy of this in the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel (Germany). In it, the story can be found of Vesalius’s end according to Solenander, written in Augsburg, and dated May 1566. This means: one year and seven months after Vesalius’ death. I only translate the most important elements:

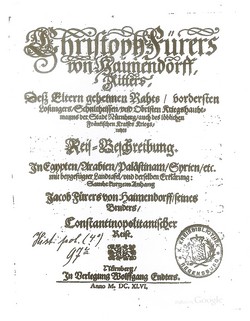

Title page of the Reis-Beschreibung by

Christoph Fürer von Haimendorf (1646)

“…, they returned to the ship. Initially, owing to stormy weather, they were driven off course, and when they had been driven into the open sea, the air became so peaceful, that the ship drifted around for several weeks, in virtually the same place. It was high summer and baking hot. Then most of the passengers fell ill, and many died. When he saw them being thrown into the sea, for several days in succession, Vesalius became dispirited, and began to suffer from sickness himself, but did not say anything about it. …, the provisions began to run out. There was a general shortage and a severe lack of drinking water. A daily ration was given to each, and not a drop more than was deemed necessary. Having ended up in this desperate situation, Vesalius, who was taciturn by nature, melancholy, and not provided for such an eventuality, received no care, as the necessary provisions had by now run out, and he started to become more seriously ill. … After they had been drifting around for a long time, the wind finally began to pick up, and they were able to sail on, with a favourable wind. In the meantime, Vesalius lay sick in the hold…. When land was sighted, everyone became frenzied, but he became even more seriously ill. Only then did the travellers arrive at Zakynthos, they called to him, and when they entered the port and struck sail, Vesalius expired, amid the creaking of the ropes and the noise of camels. But he obtained what he had most desired, namely that he should be carried ashore, and buried on land, at a chapel or shrine, near the port of Zakynthos"(13).

Vesalius’s burial place

This is how Vesalius died most probably: from illness and deprivation. But the question of his eventual burial place also arises. Numerous researchers have tried hard to gain clear information on this subject. The first person to see the grave with his own eyes was Christoph Fürer von Haimendorf (1541-1610), who in his Itinerarium (1621) states that he stopped off on Zakynthos and saw Vesalius’ grave. It is the German version of Fürer’s account of his journey, that contains the most details about Vesalius’ burial place. Not the Latin one, that appeared 25 years earlier (14).

Fürer himself, set out on a journey in July 1565, also from Venice, and headed first for Alexandria in Egypt. They sailed past Corfu, and on the 6th of August they disembarked on Zakynthos, a good seven months after Vesalius' death. He writes: “On this island there is a closter named S. Maria della Gratia, where Vesalius has been buried.” Fürer gives also a description of Vesalius’s epitaph here, because he continues: “In a grave with an epitaph carrying his coat of arms with three whippets on a shield in red, a yellow eagle, with two crowned heads, and the inscription: Tomb of Andreas Vesalius from Brussels, who died in the year 1564 on the 10th of October, on his way back from Jerusalem, at the age of 58...” This should of course be “the 15th of October” instead of the 10th, and “at the age of 50” instead of “58”. The date must be a typographical error, because his Latin text has indeed “the 15th of October”, and his abbreviation “ID” for the ides can easily be misread as a ‘ten’. Also, the description of the coat of arms is incorrect: as everyone knows, there were no whippets on it but weasels.

Solenander gives the epitaph also. According to him it reads: “Tomb of Andreas Vesalius from Brussels, who died October the 15th, 1564, on his way back from Jerusalem, at the age of 58...” Here again, the age is wrong, as Vesalius was born on the 31st of December 1514: thus he was ten weeks short of 50. As both Fürer and Solenander had the wrong age for Vesalius, this points to the fact that the epitaph might have been wrong, and not their reports.

Jean Zuallart, another Jerusalem traveller, writes that Zakynthos is an island which is highly susceptible to earthquakes, and he also mentions the grave in the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie. He saw the tomb in 1586, and tells that Vesalius was buried, on the same spot as Marcus Tullius Cicero, the famous roman writer. According to Zuallart in 1586, that is twenty-two years after Vesalius’ death, he reported that the copper memorial plaque had disappeared, having been stolen by the Turks when they plundered the island in 1571.

Pavlos Plessas was the first one to point, some years ago, to a third eye-witness of Vesalius’s grave (15). He found proof of this in an Italian translation of the worldatlas by Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598) Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. That translation was made by Filippo Pigafetta, member of an italian family of nobility from Vicenza, who added several personal experiences to the text, such as his own visit to Zakynthos. To Ortelius’s text on the Ionian Islands, accompanying Map 217, he adds in the section devoted to Zakynthos: (continued)...

Article continued here: Andreas Vesalius’s fatal voyage to Jerusalem (6).

Sources and author's comments:

12. Maurits BIESBROUCK, Theodoor GODDEERIS, Omer STEENO. ‘Reiner Solenander (1524-1601): an important 16th Century Medical Practioner and his Original Report of Vesalius’ Death in 1564 - Reiner Solenander (1524.-1601.): značajan medicinski praktičar iz 16. stoljeća i njegov izvorni izvještaj o Vezalovoj smrti 1564. godine’ in Acta medico-historica Adriatica, 2015, 13 (no. 2): 265-286, ill.

13. Reiner SOLENANDER. ‘Kurze Nachricht von des Andreae Vesalii Todt und Begräbnisz - Historia de Obitu Andreae Vesalii ex Literis Reineri Solenandri ex Comitiis August. 1566. Mense Majo’ in Thomas Theodor CRUSIUS, Vergnügung müssiger Stunden, oder allerhand nützliche zur heutigen galanten Gelehrsamkeit dienende Anmerckungen, M. Rohrlachs Wittib und Erben, 1722, pp. 483-490. The ‘work’ Vergnügung müssiger Stunden was in fact a journal that was published by Theodor Crusius in Leipzig for 20 years from 1713 to 1732; Solenander’s contribution about Vesalius’ death appeared in volume 18, 1722.

14. Christoph FÜRER VON HAIMENDORF, Reis-Beschreibung in Egypten, Arabien, Palästinam, Syrien, etc.: M. beygef. Landtafel u. ders. Erkl. Sambt Kurtzem Anh. Jacob Fürers von Haimendorff, s. Brüders, Constantinopolitanischer Reise, Nürnberg: Endter, 1646, 384 pp.

15. Pavlos [PLESSAS], ‘The tomb of Vesalius and Filippo Pigafetta’s testimony’ in Pampalaia Zakunthinès, April 3th, 2013, 4 pp., ill.; see <http://pampalaia.blogspot.com>.