Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 834 guests online

Georg Eduard Von Rindfleisch

(1836 – 1908)

German pathologist and histologist of Bavarian nobility ancestry. Rindfleisch studied medicine in Würzburg, Berlin, and Heidelberg, earning his MD in 1859 with the thesis “De Vasorum Genesi” (on the generation of vessels) under the tutelage of Rudolf Virchow (1821 - 1902). He then continued as a assistant to Virchow in a newly founded institute in Berlin. He then moved to Breslau in 1861 as an assistant to Rudolf Heidenhain (1834–1897), becoming a professor of pathological anatomy. In 1865 he became full professor in Bonn and in 1874 in Würzburg, where a new pathological institute was built according to his design (completed in 1878), where he worked until his retirement in 1906.

He was the first to describe the inflammatory background of multiple sclerosis in 1863, when he noted that demyelinated lesions have in their center small vessels that are surrounded by a leukocyte inflammatory infiltrate.

After extensive investigations, he suspected an infectious origin of tuberculosis - even before Robert Koch's detection of the tuberculosis bacillus in 1892. Rindfleisch 's special achievement is the description of the morphologically conspicuous macrophages in typhoid inflammation. His distinction between myocardial infarction and myocarditis in 1890 is also of lasting importance.

Associated eponyms

"Rindfleisch's folds": Usually a single semilunar fold of the serous surface of the pericardium around the origin of the aorta. Also known as the plica semilunaris aortæ.

"Rindfleisch's cells": Historical (and obsolete) name for eosinophilic leukocytes.

Personal note: G. Rindfleisch’s book “Traité D' Histologie Pathologique” 2nd edition (1873) is now part of my library. This book was translated from German to French by Dr. Frédéric Gross (1844-1927) , Associate Professor of the Medicine Faculty in Nancy, France. The book is dedicated to Dr. Theodore Billroth (1829-1894), an important surgeon whose pioneering work on subtotal gastrectomies paved the way for today’s robotic bariatric surgery. Dr. Miranda.

Sources:

1. "Stedmans Medical Eponyms" Forbis, P.; Bartolucci, SL; 1998 Williams and Wilkins

2. "Rindfleisch, Georg Eduard von (bayerischer Adel?)" Deutsche Biographie

3. "The pathology of multiple sclerosis and its evolution" Lassmann H. (1999) Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 354 (1390): 1635–40.

4. “Traité D' Histologie Pathologique” G.E.

Rindfleisch 2nd Ed (1873) Ballieres et Fils. Paris, Translated by F Gross

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

We would like to welcome Professor Cristián Uribe as a contributor to Medical Terminology Daily.

Prof. Uribe is a Physical Therapist, has a Masters in Human Anatomy and is a Professor in the Human Anatomy Department of the Medical School at the University Finis Terrae in Santiago, Chile.

Prof. Uribe is also the Director of the Postgraduate Course on “Anatomical Bases of Normal Imaging”, as well as the Executive Secretary of the Postgraduate Office at the same University.

He published the book “Eponyms in Anatomical Nomenclature” (2011, Ed. U. Finis Terrae). For his LinkedIn page click here.

- Details

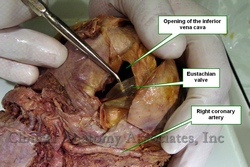

The [valve of the inferior vena cava] is probably better known by its eponym, the [Eustachian valve]. This is an incomplete valve found at the most distal end of the inferior vena cava, at the point where it opens into the right atrium of the heart. The valve is muscular at its base and composed mostly by membranous endocardium, and is normally the only valve present in the inferior vena cava.

It appears as a membranous semilunar fold extending posteriorly from the limbus fossa ovalis, anterior to the inferior caval orifice where it disappears. Its free border is usually membranous, concave, and directed anterosuperiorly. Its base is a transverse muscular ridge continuous with the anterior margin of the caval orifice.

It has no function in the adult, but in the fetus it helps to divert the flow of blood coming from the inferior vena cava towards the foramen ovale [fossa ovalis], as part of fetal circulation.

It has great anatomical variation in size, shape and thickness. On its medial aspect it joins with the Thebesian valve at the orifice of the coronary sinus.

First described by Bartolomeo Eustachius (c1500 - 1574) in 1653, the existence of the valve of the inferior vena cava was disputed by many until Winslow in 1717 confirmed its presence and suggested its function in fetal circulation.

Sources:

1. "The Valve of the Inferior Vena Cava" Hickie, JB Br Heart J. 1956 Jul; 18(3): 320–326

2. "Bartolommeo Eustachio; a great medical genius whose masterpiece remained hidden for 150 years" Wells, WA Arch Otolaring (1925) 48: 58

- Details

The medical word [dysphagia] arises from the suffix [dys-] which means "abnormal", the root term [phag-] which arises from the Greek [φάγος] (phagos), meaning "to swallow", a "glutton" or "eating much", and the suffix [-ia] meaning "condition". The word dysphagia then means "a condition of abnormal swallowing".

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Bartolomeo Eustachius

Bartolomeo Eustachius (c1500 - 1574) Italian physician and anatomist, also known as Bartholomew Eustachius, Esutachi, and e was born in the small town of San Severino Marche, in the province of Macerata, central Italy. His father was a respected physician, and may have attended as a student the University of Sapienza, where he later taught as a professor of practical medicine. Eustachius’ life is mostly unknown and some of his works remained hidden for over 150 years. His birth date is only an estimate and data varies from c1500 AD to c1510 AD.

It is known that Eustachius lived and worked in Rome from 1549 to 1574. He was both an anatomist and a physician to the Vatican. As an anatomist, Eustachius is credited for having been the first to prepare anatomical images for printing using copper plates.

As a hospital physician, Eustachius was adamant on the need of autopsies on patients who died at the hospital, crediting him with being one of the first pathological anatomists.

Eustachius’ is credited with several anatomical discoveries, which he published in short monographs, on topics like the kidneys, the suprarenal glands (which he was the first to describe), the movements of the head, the azygos vein, etc. One of these was entirely dedicated to dentistry, “Libellus de Dentibus”, which have led to some to call Eustachius “The Father of Dental Anatomy”.

Eustachius dedicated himself to prepare a number of anatomical copper plates, apparently getting ready to publish a book to rival Vesalius’ “Fabrica”. It is known that Eustachius disliked Vesalius because of Vesalius’ contempt for the teachings of Galen. Eustachius died before completing his work and the copper plates were forgotten for over a century. After being rediscovered, these plates were published with commentaries by anatomists, until a final publication in Latin by Bernard Siegfried Albinus (1697 – 1770) entitled “Explicatio Tabularum Anatomicarum Bartholomaei Eustachii Anatomici Summi” (An explanation of the Anatomical Picture of Bartholomew Eustachius, Supreme Anatomist”.

Besides the suprarenal gland, Eustachius is credited for having discovered the stapes, the tensor tympani muscle, the valve of the inferior vena cava, the cervical sympathetic chain and the thoracic duct.

Interesting note: Eustachius’ assistant Petrus Matthaeus Pinus, who helped develop the copper plates, voiced his master’s dislike of Vesalius in a poem that was published by Albinus over a hundred years after the death of all of them, it is also an epitaph for a great anatomist:

“Just as the Master from Pergamon (Galen)

Teaching his method of healing, once refuted

The false writings of the ignorant Thessalus,

So also my BARTOLO (Eustachius)

Teaching his method of denoting every detail, position,

Shape, structure, order, number and condition

Has repulsed the shameless arrogance and claims

Of the impudent Vesalius

To him (Eustachius) all future generations

Adhere In reverential admiration

The age to come will envy us on account of you Father,

And historians will wish they had lived sooner

They will extol our era, through you fortunate,

Lucky beyond measure"

Sources:

1. "The root of dental anatomy: a case for naming Eustachius the "Father of Dental Anatomy"" Bennett, G (2009) J Hist Dent (1089-6287), 57 (2) 85 -88

2. “The papal anatomist: Eustachius in renaissance Rome” Simpson, D, ANZ J Surg (2011) 81: (12)905 -910

3. “Bartholomeo Eustachio – The Third Man: Eustachius Published by Albinus” Fahrer, M. (2003) ANS J Surg; 73: 523- 528

4. "Bartolommeo Eustachio; a great medical genius whose masterpiece remained hidden for 150 years" Wells, WA Arch Otolaring (1925) 48: 58

Original image courtesy of: Wikimedia Commons.

- Details

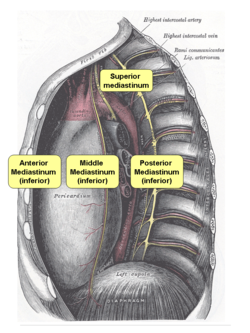

UPDATED: The mediastinum is the median region of the thorax, usually described as the "space"1 between the lungs. This region is divided into a superior and inferior mediastinum by a plane that pases through the sternal angle or Angle of Louis.

The inferior mediastinum is itself divided into three separate regions by the pericardial sac. The region anterior to the pericardial sac is the "anterior mediastinum", the region posterior to the pericardial sac is the "posterior mediastinum", and the region containing and including the pericardial sac is the "middle mediastinum". Thus described the mediastinum comprises four regions as follows:

• Superior mediastinum: It contains the aortic arch, the brachiocephalic trunk, the thoracic segments of the left common carotid and the left subclavian arteries, the brachiocephalic veins, a portion of the superior vena cava, the vagus nerve, phrenic nerve, and left recurrent laryngeal nerve, trachea, esophagus, thoracic duct and the remains of the thymus gland

• Anterior mediastinum: A narrow space, more developed on the left side, anterior to the pericardial sac and contains some lymph nodes and connective tissue

• Middle mediastinum: The largest mediastinal region, it contains the pericardial sac, the heart, the bifurcation of the trachea, the inferior vena cava, and the cardiac end of the great vessels.

• Posterior mediastinum: Contains the descending aorta, the azygos and hemiazygos veins, the esophagus, and thoracic duct.

Personally, I do not use the description of the mediastinum as a "the space beween the lungs", as it conjures the image of literal "open spaces" around or between the organs. The fact is that the mediastinum is tightly packed with no spaces between the organs. This is why I prefer the definition of the mediastinum as an "area" or "region" between the lungs. Dr. Miranda.

- Details

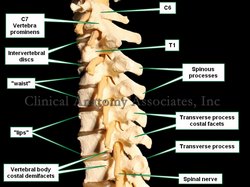

There are two types of [costal facets]: costal demifacets, and transverse costal facets.

The first type are small, half-moon shaped facets found in the posterior aspect of the vertebral body of thoracicvertebrae. They are called demifacets, from the French word [demi], which itself derives from the Latin [dimidius] meaning "split in two" or "halved". A demifacet is "half a small face". There is usually one larger superior demifacet and a smaller inferior demifacet, both close to the area where the vertebral body meets the pedicle. Anothe term for each demifacet is a fovea costalis. The articulation of two adjacent demifacets and one rib form a costovertebral joint.

The second type are articular facets found in the transverse processes of the thoracic vertebrae. These allow most of the rib to articulate with the same number vertebra (T1 - Rib 1, T2 - Rib 2, etc). The articulation of a transverse costal facet and one rib form a costotransverse joint.

There are specific variations to these facets and joints as follows:

• T11 and T12 do not have transverse costal facets

• T1 has a complete superior costal facet for rib #1 and an inferior demifacet for rib #2

• T11 and T12 have a complete costal facet on their vertebral body, no demifacets

Image property of: CAA.Inc. Photographer: David M. Klein