Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 344 guests online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

First used by Galen of Pergamon (129AD - 200AD) the word [etiology] is of Greek origin. [αiτία] or [aitia], meaning "cause" or "reason", and [λογία] or [-ology], meaning "study of". Etiology is the "study of cause". In medicine this word is used to denote the study of the causes for a pathology, disease, or condition.

Because of its Greek origin, Skinner (1970) states that the proper way of spelling this term should be aetiology, but the initial "a" has been discarded through use.

There are many pathologies of unknown origin. In this case the word to use would be [idiopathic] or [idiopathy] meaning "of unknown cause"

- Details

The suffix [-(o)cele] arises from the Greek [κήλη] meaning "dilation" or "pouching". In medical terminology this suffix is used to mean "hernia", "bulging", or a "dilation". In older times a synonym was used for hernia: "rupture".

Dr. Aaron Ruhalter would state the proper description for an "ocele" is that of a prolapse, that is, a herniation without a hernia sac.

Examples the use of [ocele] are:

- Orchiocele: The prefix [orchi-] means "testicle" or "scrotum". Refers to a scrotal or testicular bulging, a scrotal hernia

- Hydrocele: The root term [-hydr-] means "water". A watery dilation. Usually used to refer to the accumulation of fluids in the scrotum

- Hydatidocele: Refers to a dilated cyst containing hydatids, the larval form of the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus or Echinococcus multilocularis

- Enterocele: The root term [-enter-] means "intestine" or "small intestine". The bulging of the small intestine into the vagina because of weakness of the vaginal wall

- Cystocele: The root term [-cyst-] means "bladder" or "sac". The bulging of the urinary bladder into the vaginal canal because of weakness of the vaginal wall

- Cystourethrocele: A combination of root terms; [-cyst-] means "bladder" or "sac" and [-urethr-] means "urethra". The bulging of the urinary bladder and urethra into the vaginal canal

- Myelomeningocele: A combination of root terms; [-myel-] means "spinal cord" (also "bone marrow") and [-mening-] means "menynx". The herniation of the spinal cords and its meningeal coverings into the back, creating a bulge

- Varicocele: The root term [-varic-] means "varix" or "sac". A bulging of the skin caused by varices

- Details

The suffix [-(o)penia] arises from the Greek [πενία] or [penia], meaning "poverty" or "to lack". In medical terminology this suffix is used to mean "a deficiency", or "lack of". Examples of its use are:

- Leukopenia or leukocytopenia: A combination of root terms; [leuk], means "white", and [-cyt-] means "cell". A white cell deficiency

- Pancytopenia: The prefix [pan] means "wide" or "many". The term refers to the deficiency of a wide variety of cells, in this case, blood cells

- Neutropenia or neutrocytopenia: Refers to the deficiency of neutrophil cells or polymorphonuclear leukocytes, The most common type of white blood cells

- Osteopenia: The root term [-oste] means "bone". A bone deficiency, not low enough to be classified as osteoporosis

- Erythropenia: The root term [-erythr-] means "red". A deficiency of red blood cells

- Details

The right coronary artery (RCA) is one of the two branches that arises from the ascending aorta and provide blood supply to the heart. The RCA begins at the coronary ostium, situated usually within the right sinus of Valsalva found in the aortic valve, one of the semilunar valves of the heart.

The RCA gives off in its initial course two arteries: the conus artery, which gives blood to the conus arteriosus, the outflow tract of the right ventricle, and the artery to the sinoatrial (SA) node, a component of the conduction system of the heart.

The RCA descends in the atrioventricular sulcus, giving off a series of small right ventricular branches and a couple of small right atrial branches, it then bends around the acute margin (margo acutus) and passes to the posterior surface of the heart. Just before the RCA bends posteriorly, it will give off the acute marginal artery, usually a thin, longer branch that extends towards the cardiac apex.

In its posterior trajectory the RCA gives off a couple of small posterior right ventricular arteries and then ends at the crux cordis, where the RCA gives off the posterior interventricular artery, commonly known as the posterior descending artery (PDA). The RCA will also give off the posterolateral artery, which, situated in the atrioventricular sulcus, extends the vascular territory of the RCA into the region of the left ventricle. This origin of the PDA from the RCA is subject to anatomical variation, which gives origin to the concept of coronary dominance.

Arising from the terminal portion of the RCA (sometimes from the posterolateral artery) is the artery to the atrioventricular (AV) node, another component of the conduction system of the heart. It is easily understood that stricture or stenosis of the RCA (depending on location) can then lead to damage of the conduction system of the heart.

Human heart and coronary artery anatomy and pathology are some of the many lecture topics developed and presented by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc.

Image property of: CAA.Inc.Artist: Victoria G. Ratcliffe

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

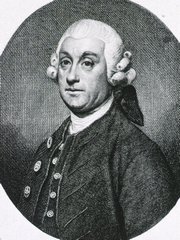

Sir Percival Pott

Sir Percival Pott (1714 – 1788)

English surgeon and anatomist, Percival Pott was born in London on January 6, 1714. His name has the alternate spelling Percivall. In 1729 Pott started his apprenticeship with a surgeon, William Nourse. At age 22 he received the diploma from the Company of Barber Surgeons, and by age 34 he became a full independent surgeon at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. In 1753 Percival Pott was elected, with William Hunter, as Master of Anatomy at Surgeon’s Hall

His name is eponymically remembered in “Pott’s fracture”, a condition that apparently he himself suffered and that kept him in bed writing several of his most important works. This historical account is refuted by many and could be legend. The fact is that Percival Pott did write about what today is known as “Pott’s fracture”.

Percival Pott was elected to the Fellowship of the Royal Society in 1764 and became Governor of the Company of Barber Surgeons in 1765.

Pott was one of the first to recognize a condition caused by industrial working conditions when he diagnosed “Chimney Sweeper’s Cancer” a scrotal cancer caused by the exposure to soot and poor working and personal hygienic conditions.

Some of Pott’s eponyms:

- Pott’s fracture: Fracture of the fibula superior to the lateral with rupture of the medial ligament and outward displacement of the foot

- Pott’s disease: Spinal tuberculosis with hyperkyphosis

- Pott’s puffy tumor: Edema of the scalp due to underlying osteomyelitis and suppuration

Sources:

1. "Sir Percival Pott" Ann R Coll Surg Engl (Suppl) 2011; 93:66–67

2. “Percivall Pott (1714–1788) and chimney sweepers’ cancer of the scrotum” Brown JR, Thornton JL. Br J Ind Med 1957; 14: 68–70

3. "Percival Pott; Pott's fracture, Pott's disease of the spine, Pott's paraplegia". Harold, E. J Periop Pract, 22 (11), 366

4. “The Origin of Medical Terms” Skinner, HA 1970

5. “Dictionary of Medical Eponyms” Firkin, BG; Whitworth JA 1987

6. “Invective in surgery: William Hunter versus Monro Primus, Monro Secundus, and Percival Pott” Ravitch. MM, Bull N Y Acad Med. 1974; 50(7): 797–816

7. “Percivall Pott” Dobson, J. Ann Roy Coll Surg Eng 1972: 50; 50-65

Original image courtesy of "Images from the History of Medicine" at www.nih.gov

- Details

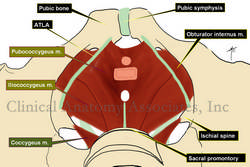

The [iliococcygeus muscle] is one of the muscles that forms the pelvic diaphragm. It is the more superficial and one of the two muscular components of the levator ani muscle, the other one being the pubococcygeus muscle.

The iliococcygeus muscle attaches anterolaterally to a thickening of the deep fascia of the obturator internus muscle called the Arcus Tendineous Levator Ani (ATLA).

It attaches posteriorly to the sacrococcygeal region and posteromedially it attaches to a medial ligamentous structure that stretches between the anal canal and the coccyx, the anococcygeal ligament or anococcygeal raphe.

Some fibers of both the iliococcygeus and the pubococcygeus muscles continue inferiorly between the external and internal anal sphincters. This is known as the "conjoined longitudinal muscle of the anal canal" and it is one of the few areas in the human body where there is a mixing of both smooth (involuntary) muscle and striated (voluntary) muscle.

Image property of: Photographer: David M. Klein