Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 1509 guests online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

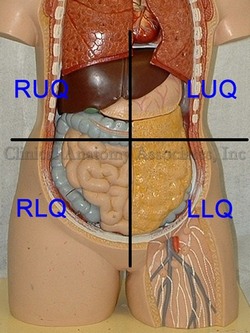

A simple surface anatomy division of the abdomen is into four quadrants. A more detailed division of the abdomen is into nine abdominal regions.

The abdominal quadrants are formed by two planes. The first is the midsagittal or median plane. The second one is a transverse or horizontal plane that passes through the umbilicus. This creates four quadrants with specific content as follows:

Right Upper Quadrant (RUQ): This quadrant contains most of the liver, with the gallbladder, portal vein, the distal portion of the stomach, duodenum, head of the pancreas, part of the ascending colon, part of the transverse colon, the right flexure of the colon, and the right kidney and right adrenal gland

Left Upper Quadrant (LUQ): This quadrant contains the tip of the left lobe of the liver, most of the stomach, spleen, body and tail of the pancreas, part of the transverse colon and the left colic flexure, and the left kidney and left adrenal gland

Right Lower Quadrant (RLQ): This quadrant contains the cecum and ascending colon, vermiform appendix, right ovary, the ileocecal junction, right ureter, part of the small intestine, and the right half of the greater omentum

Left Lower Quadrant (LLQ): This quadrant contains the descending colon, sigmoid colon, left ovary, part of the small intestine, and the left half of the greater omentum

- Details

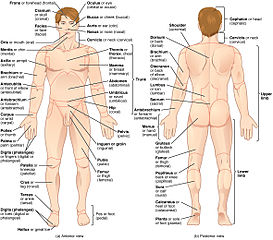

Continuing on the topic of surface anatomy, the surface of the body has been divided into anatomical regions which are used to describe locations on the body.

The number of regions varies according to different authors and even the boundaries of these regions are sometimes not clearly delineated and will vary from author to author. Still, these regions are the basis of surface anatomy.

The human body as a whole can be divided into eight basic regions:

• Head

• Neck

• Torso (itself divided into abdomen and thorax)

• Superior extremities (not to be confused with “the leg”)

• Inferior extremities (not to be confused with “the arm)

The division of thorax and abdomen is not clearly evident, as the respiratory diaphragm, which is considered the boundary between them is curved. The abdomen is divided into nine abdominal regions and four abdominal quadrants.

Original image courtesy of Connexions (http://cnx.org) [CC-BY-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Philippo Verheyen

Philippo Verheyen (1648 – 1710). Flemish physician and anatomist, Philipo (Philip) Verheyen was born in the city of Verrebroek in Belgium, worked as a farmer in his early years and was probably expected to be a farmer for the rest of his life. The local Catholic parish pastor Johannes Jaspars, recognizing his intelligence, started teaching him Latin and letters with the intention of having Philip become a priest.

In 1672, he was sent to the Trinity College in Leuven where he started his studies in arts and later in theology. He continued his studies in Theology at the Collegium Sancti Spiritus (College of the Holy Spirit). During the latter part of his studies Verhayen was already wearing a priest’s collar. In 1675 Verheyen suffered an injury that lead to gangrene and eventual amputation of his left leg. This injury prevented him from taking his final vows as a priest.

Verheyen enrolled at the University of Leuven College Of Medicine where after 3 years he became a physician. Unhappy with his mostly theoretical medical knowledge Verhayen moved to Leyden to continue his studies with Frederick Ryus and others.

In 1683 Verheyen returns to Leuven where he presents his doctoral thesis which is accepted. In August 1669 elected Rector Magnificus at the University of Leyden, one of the highest honors ever bestowed on him. This is why Verheyen's statue is among the personalities honored at the town hall in Leuven, Belgium.

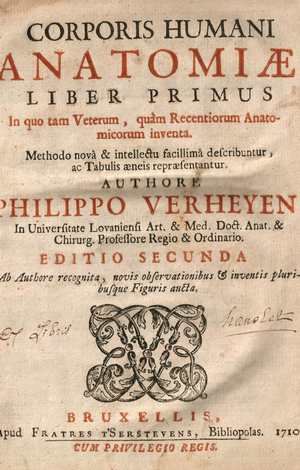

Verheyen was a prolific writer including several books and manuscripts. His main work “Corporis Humani Anatomiae”, a two book work, had twelve editions, some in other languages besides Latin. This book became one of the most used anatomy books until the middle of the 18th century. Interestingly, Verheyen relates his life and studies at the beginning of his book in a chapter call Compendium Vitae (CV). Only the first edition was published while Verheyen was alive.

The following excerpt of his book "Corporis Humani Anatomiae Liber Primus" reads : " ... QuintusAuricularis, quia cum minimum sit, auribus expurgandis est aptissimus" translates as"..the fifth (finger, called) Auricularis, because how small it is, is most suitable to clean the ears". Incredibly, anatomists at that time called the fifth digit "digitus auricularis".

Verheyen is credited with the creation of the eponym the “Achilles tendon” which denominates the common tendon for the gastrocnemius and soleus muscle, although at the time he called it the “Chorda Achillis”. He also described the kidneys in detail, especially the arterial “stars” found on the surface of the kidney, which are today known as the “Stars of Verheyen”.

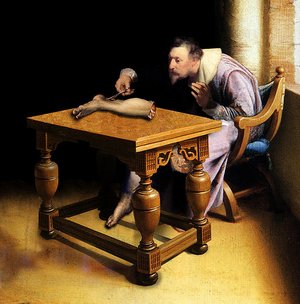

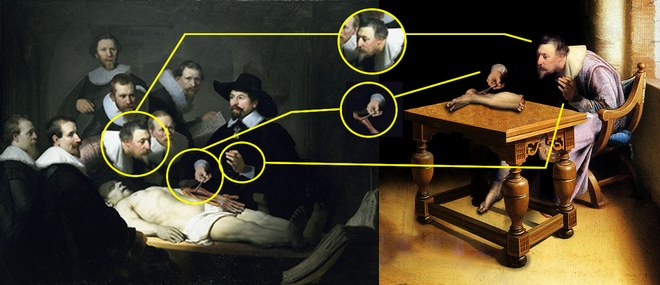

In 2005 an article appeared on the World Wide Web with a painting showing Verhayen dissecting his own amputated leg. This initially “anonymous” oil pintingis actually a Photoshop-edited image which incorporates parts of the painting “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp” by Rembrandt. This work was made by ShrestaRit Premnath. This is a conceptual artwork depicting the concept of amputation, but not an actual oil painting, as shown by the image analysis depicted at the bottom of this article.

The story of Verheyen keeping and dissecting his own leg is most probably a myth for several reasons. Verhayen was poor and did not have enough money to go to Leyden to have his leg amputated there as the myth suggests. Preservation techniques were not too good at the time and when Verheyen had his leg amputated he had yet to enter medical school and be introduced to the art of human anatomy. Granted, he had dissected animals before in the farm, but it is doubtful that this myth is true.

Click on the image for a larger version.

The image above shows a comparison between Rembrandt's painting “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp” and an "anonymous" oil painting that appeared on the Internet circa 2005.

This oil painting include elements from Rembrandt's work. First, the head of "Verheyen" has been copied and flipped horizontally, This causes "Verheyen's" neck position to be awkward for the job of dissection. Second, the right hand holding the dissector and Achilles' tendon is Dr. Tulp's hand that has been slightly rotated, including the instrument anf the cuff. Third, the left hand is also that of Dr. Tulp, but not the cuff. If you look closely you will notice that both cuffs are different!

I have not been able to find the original painting on which these elements were added. My guess is that the left leg depicted on the table is also added. Interestingly, the table shows perspective problems.

In 2023 I had the honor of being invited by the University of Antwerp in Belgium to speak at the 2023 Vesalius Triennial Meeting in the city of Antwerp, Belgium. While there I visited Verrebroek, the city where Verheyen was born.

Personal note: I am proud to have in my library catalog a copy of the second edition of Philippo Verheyen's “Corporis Humani Anatomiae, Liber Primus”, published in 1710 in Brussels by the printer house of Fraters Serstevens. The book is signed by an Ex-Libris by "Hanolet". I have not been able to find more information on this prior owner of this book. An image of the title page is depicted in this article. Dr. Miranda

Sources

1. “Philip Verheyen (1648-1710) and his Corporis Humani Anatomiae” Suy R. Acta chir belg, 2007, 107, 343-354

2. “Achilles tendon: the 305th anniversary of the French priority on the introduction of the famous anatomical eponym” Musil, V. et al Surg Radiol Anat (2011) 33:421–427

3. "Philip Verheyen" Research and movie by digitalstories.be by Hedwige Daenens

Original image courtesy of the National Library of Medicine

- Details

This is the second most popular article on this blog!

Look at the hits counter on this article...

Image property of: CAA.Inc.. Artist: M. Zuptich.

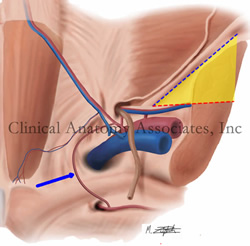

The so-called "triangle of pain" is a misnomer coined by laparoscopic hernia surgeons who observed the anatomy of the inguinofemoral region from the posterior aspect and refers to an inverted "V" shaped area which should be avoided because of the potential to damage nerves when placing staples, tacks, or sutures to anchor a mesh during a laparoscopic herniorrhaphy.

An example of a similar situation with terminology is the so-called "triangle of doom". It is also not a triangle, as it only has two boundaries. similarly, it does indicate an area where it is dangerous to place staples or sutures during laparoscopic hernia surgery.

The "triangle of pain" is an inverted "V" shaped area with its apex at the internal (deep) inguinal ring. It is bound anteriorly by the iliopubic tract / inguinal ligament and by the testicular (spermatic) vessels posteromedially. This "triangle" has no defined posterolateral boundary. although you can see it in drawings by some authors.

The reason why this area should be avoided and not place staples or sutures to anchor a hernia mesh is that there are several nerves which usually cannot be seen as they run just deep to the endoabdominopelvic fascia.These nerves can suffer damage or entrapment when performing a laparoscopic herniorrhaphy and cause pain (hence the name of the area) as well as motor and sensory disorders.

The nerves are:

• Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve: arising from the ventral rami of L2 and L3, this nerve provides sensory innervation to the anterior skin of the thigh

• Femoral nerve: arising from the ventral rami of L2, L3, and L4, this nerves provides motor and sensory innervation to the anterior compartment of the thigh as well as sensory branches to the hip joint

• Genitofemoral nerve: arising from the ventral rami of L1 and L2, this nerve divides anterior to the psoas major muscle into two branches. The genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve enters the inguinal canal and provides sensory and motor innervation to the scrotum and cremaster muscle, as well as the labia majora and mons pubis. The femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve enters the "triangle of pain" region and passes inferior to the inguinal ligament to provide sensory cutaneous innervation to the superior aspect of the thigh.

The image shows a posterior view of the inguinal region. The "triangle of pain" is depicted in yellow. The iliopubic tract / inguinal ligament is shown by a blue dotted line while the testicular vessels boundary is shown by a red dotted line. The blue arrow points to the aberrant obturator artery (Corona Mortis).

Thanks to Steve Pearson for suggesting this term. Medical illustration by Mark J. Zuptich.

Clinical anatomy of the inguinofemoral hernias, as well as abdominal and perineal hernias are some of the lecture topics developed and delivered to the medical devices industry by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. For more information Contact Us.

- Details

The noun word [porta] is Latin and means "gate" or "door". The adjectival form [portal] means “pertaining to a door”. These terms are used in anatomy and pathology to denote the entrance to an organ.

• porta hepatis: The entrance or "door" to the liver

• portal vein: The vein that enters through the porta hepatis

• portal system: A system of veins that collects the venous return from the digestive system and derives it through the portal vein into the liver

• portal hypertension: A pathological condition of higher blood pressure in the portal vein system.

- Details

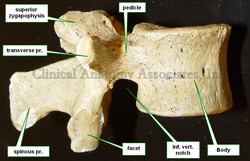

The lumbar region of the spine is composed by five lumbar vertebrae. Although sharing characteristics common to all vertebrae, a lumbar vertebra can be differentiated by the following:

• The vertebral body is large, tall, and when viewed from superior, the vertebral body has a longer transverse diameter and a shorter anteroposterior diameter. Most anatomists describe the vertebral body as being “kidney-shaped”. The massiveness of the vertebral body is due to the larger weight that each consecutive vertebra has to bear in the lumbar region. Because of this, lumbar vertebrae have larger anular epiphyses, and the vertebral body is hourglass-shaped with a “waist”. As with other vertebrae, the body of a lumbar vertebra has vertebral endplates, nutritional foramina, and in its posterior aspect they present with basivertebral foramina.

• The pedicles in the lumbar vertebrae are larger, course in a mostly anteroposterior direction, and have a oval cross-section where the superoinferior diameter is longer and the transverse diameter is shorter. This is important for transpedicular procedures for vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore

• The transverse processes are also larger than other vertebrae. Of interest are the facts that the transverse process of the third lumbar vertebra is the longest of all lumbar vertebrae and that the transverse process of the fifth lumbar vertebra courses superolaterally at an angle of almost 45 degrees because of the presence of the strong iliolumbar ligament. The lumbar transverse processes have a small tubercle called the mammillary process.

• The lumbar spinous processes are large and have a square shape.

Again, because of the larger weight bearing capacity of the lumbar vertebrae, they have strong ligaments and their zygapophyseal joints and articular facets tend to be oriented with their surfaces in a transverse plane. This has two consequences: The rotational mobility of the whole lumbovertebral region is limited and they tend not to have anteroposterior displacement.

Image property of CAA.Inc. Photographer: D.M. Klein.