Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 823 guests online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

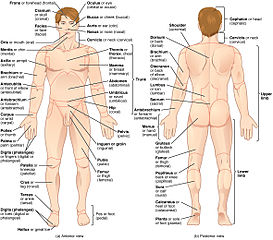

The [leg] is the anatomical region found between the knee joint superiorly and the ankle inferiorly. It contains two bones, the tibia and the fibula (os peroneus).

Since the Latin word [crus] means “pillar” or “leg”, the term [crural] is sometimes used to denote the leg region.

The wrong usage of the term [leg] to refer or denote all of the lower extremity is one of my pet peeves. There are many health care professionals who use this term wrongly and are therefore forced to use the terms “upper leg” to refer to the thigh, and “lower leg” to refer to the leg proper.

The posterior compartment of the leg contains the soleus and gastrocnemius muscles which cause a superficial elevation known as “the calf”. The Latin term [suram] means “calf”, so the term [sural] can be used to denote the posterior aspect of the leg.

The anterior aspect of the leg is marked by the bony anterior tibial crest or shin, a word that is sometimes wrongly used to mean “leg”.

Original image courtesy of Connexions (http://cnx.org) [CC-BY-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

- Details

Although this article is called “How to Read Medical Terms”, a better title would have been “How to Translate Medical Words” because that is what we do, we translate terms which have multiple linguistic origins to vernacular English.

Medical words are not read as we normally read English, from left to right. Rather, they are read in an order related to their components, prefixes, root terms, suffixes, and combining vowels.

Let’s take as an example the word [preperitoneal], where the prefix is [pre-], the root term is [-periton-] and the suffix is [-eal]. Read in normal left to right English the word would translate as “anterior (aspect of) peritoneum pertaining to”, which does not sound correct.

The proper way is to read the suffix first, the prefix second, and the root term last. Thus, this translation would read as “pertaining to (the) anterior (aspect of) the peritoneum”. There are exceptions of course, but the rule presented here applies to most medical words.

In the absence of the prefix, the word is translated suffix first and root term second.

When a word contains combined root terms they are read in the way they are written, from left to right, as they will have already been placed in a proximal to distal relationship, otherwise the word would be wrongly constructed.

There are more nuances to Medical Terminology, but they go beyond the objectives of "Medical Terminology Daily". For a complete course on Medical Terminology for your company, contact CAA, Inc.

Image property of: CAA.Inc.- Details

Most medical words have only one root term and do not require combination as in the word [colectomy]. The situation arises when there is more than one organ or structure that is influenced by the suffix and the prefix (when present), such as [coloproctectomy]. Following are the basic rules for root terms combination:

- - Place an [-o-] between the root terms being combined. The combining vowel [o] means "and". The word [gastroenterology] means "study of the stomach and the small intestine"

- - Organize the root terms using their proximal to distal relationship. For a better explanation, click here

- - If the first root term ends in a vowel, the combining vowel [-o-] is not needed. An example are the root terms [-chole-], meaning "bile or gall". and [cyst], meaning "bladder or sac". The word [chole-cyst-ectomy] does not have an [-o-] between the root terms

- - If the proximal to distal relationship does not apply, then the words should be ordered in a way that is euphonic

- - The only time a hyphen should be used is the rare case when using an [o] is not possible. Based on this rule, the word [salpingooophorectomy] is correct, the word [salpingo-oophorectomy] is not. An example of this is the word [cross-section].

An example of rule #5 is the word co-author. Since adding an [o] as a combining vowel would give us the word cooauthor (which is not correct), a hyphen must be used.

In the case of the word [coloproctectomy] the word can be divided into these components" The first root term [-col-], meaning "colon", the combining vowel [-o-], meaning "and", the second root term [-proct-], meaning "rectum", and the suffix [-ectomy], meaning "removal of". Properly read, the word means "removal of colon and rectum]. The proper term is [coloproctectomy], please do not use the terms [proctocolectomy] or worse, [protocolectomy], because they are incorrect usage of medical terminology.

For information on how to read medical words, click here.

There are more nuances to Medical Terminology, but they go beyond the objectives of "Medical Terminology Daily". For a complete course on Medical Terminology for your company, contact CAA, Inc.

Image property of: CAA.Inc.- Details

In medical terminology there are many adjectival suffixes that transform a root term into an adjective. In general these adjectival suffixes have the meaning of "pertaining to", and complete the word. In many cases the adjectival suffix can be omitted and simply refer to the root term.

An example of this is the suffix [-ic] in the word [gastric], added to the root [-gastr-] meaning "stomach". The word [gastric] then means "pertaining to the stomach", or more simply stated, "stomach". The following lists some of the adjectival suffixes and examples of its use. For brevity, we have not given the root term meaning, but they can be inferred.

• -ic: Gastric; pertaining to the stomach, stomachal, or stomach

• -eal: Esophageal; pertaining to the esophagus, or esophagus

• -ar: Ocular; pertaining to the eye, or eye

• -ose: Adipose; pertaining to, or full of, fat. Refers to fat or fatty tissue

• -ine: Uterine; pertaining to the uterus or uterus

• -al: Surgical; pertaining to surgery or surgery

For information on how to read medical words, click here.

- Details

The suffix component of a word is found at the end of a medical word after the root term(s) and also alters or influences the meaning of the root term. In the words [planter], [planted], and [planting] the suffixes are [-er], [-ed], and [-ing]. Some of the most simple suffixes are adjectival suffixes such as [-ic], [-al], [-eal], etc. all of them meaning "related to" or "pertaining to".

In medical terminology, the use of each root term can be multiplied many times over by the addition of prefixes and suffixes. Using the root term [-gastr-], meaning "stomach", we can form: [gastric], [gastritis], [gastrotomy], [gastrectomy], [gastrostomy], [gastrorrhaphy], [gastrography], [gastroscope], [gastroscopy], [gastropod], [gastroma], [perigastritis], [endogastritis], [intragastric], [epigastric], etc.

For information on how to read medical words, click here.

The listing of medical suffixes is quite large and should be mastered by professionals in the medical industry. Medical Terminology is one of the core competencies of CAA, Inc.

Image property of: CAA.Inc.- Details

All words have a foundation, called a root or a root term. The root is the minimal expression of a word that conveys a specific meaning. The word [hepa] does not mean liver, but the root term [-hepat-] does. There are some root words that have two presentations, like [-card-] and [-cord-], both meaning "heart", and even three presentations such as [-uter-], [-metr-], and [-hyster-], all of them meaning "uterus". All these following words have root terms meaning "uterus": periuterine, endometrium, and hysterectomy.

As an example, all the following medical terms: [pneumonectomy], [pneumonia], [pneumonitis], [pneumogastric], [pneumobacillus], and [pneumothorax] have the same common root term [-pneumon-], from the Greek [πνεύμονας], meaning "lung".

In medicine, surgery, and human anatomy there are several cases where there is more than one root term for the same organ. The terms [lienectomy] and [splenectomy] both mean "removal of the spleen", as the root terms [-lien-] and [-splen-] both mean "spleen". The same is the case in the following pairs: [-nephr-] and [-ren-], meaning "kidney"; [-cyst-] and [-vesic-], meaning "bladder"; [-pneumon-] and [-pulmon-], meaning "lung"; etc.

Root terms can also be combined to form complex medical terms, such as [gastroenterology], [leiomyomata], [cholecystectomy], [dacryocystolithectomy], [nephroureterocystourethrectomy], etc. To do this there are specific rules for combination.

For information on how to read medical words, click here.

Image property of: CAA.Inc.