Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 863 guests online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

A prefix is a component of a word that precedes the root term and alters or influences the meaning of the root term. The root [port], from the Latin [portare], meaning "to carry" is found in the words export, support, and transport. The prefixes are [ex-], meaning "outside"; [sup-], meaning "above or on top"; and [trans-], meaning "across".

The same is true for medical terms. The words suprahepatic, infrahepatic, and transhepatic, all contain the root term[-hepat-] from the Greek [hepar], meaning "liver". The prefixes are [supra-], meaning "superior or above"; [infra], meaning "inferior or below"; and [trans], meaning "through or across".

For information on how to read medical words, click here.

The listing of medical prefixes is quite large and should be mastered by professionals in the medical industry. Medical Terminology is one of the core competencies of CAA, Inc.

Image property of: CAA.Inc.- Details

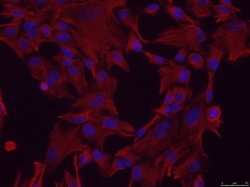

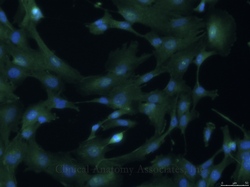

The word [mesenchymal] is the adjectival form of [mesenchyme] which arises from the Greek combination of [μέσο] (meso) meaning “middle”, and [χυμός] (chymos) meaning “juice”. In the early physiological theory of “humors” it refers to a type of “juicy” organ tissue. These organs needed to be activated by a thick fluid.

The term was used in embryology in 1881 to denote a portion of the mesoderm formed by loose cells that give origin to connective tissues.

The original meaning of the term [mesenchyme] has no application today, except being used to denote a tissue characterized by loose cells that are surrounded by a large extracellular matrix. Mesenchymal cells are able to develop into tissues of the lymphatic and circulatory systems, as well as connective tissues throughout the body, including bone and cartilage.

Some mesenchymal cells in the adult can be harvested and used as somatic stem cells.

Sources:

1. "The Origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, HA 1970 Hafner Publishing Co.

2. "Human Embryology" WLJ Larsen 1993 Churchill Livingstone

Note: The links to Google Translate in these articles include an icon that will allow you to hear the Greek or Latin pronunciation of the word.

- Details

- Written by: Dr. O'Garcia

The word [somatic] traces its origins to the Greek word [σώμα] (soma) meaning “body” and [σωμαkwς] (somatikos) meaning “of the body”, “bodily”, or “physically”. Combining the root term [-soma-] with the adjectival suffix [–tic], meaning “pertaining to”, gives the word [somatic], meaning “pertaining to the body”. Combining the root term [-psych] with the root term [-soma-]”,and adding the suffix [–tic], meaning “pertaining to”, gives us the medical word [psychosomatic] that means “pertaining to the mind and body”.

This term has become commonplace in scientific and medical literature, especially in cellular medicine describing stem cells, and at other times the word is appended with a prefix or suffix and used in another capacity. Often overlooked, because of the words it precedes (e.g., somatic stem cells), the word somatic is an important qualifier and adjective in defining a type of cell, or anything pertaining to the body for that matter. Thus, we examine the origins of this word, and why understanding it’s meaning can serve to as a critical adjective in cellular medicine.

Important to note, is that included in this word origins, is the designation that the root term [-soma-] is specific to the body and is distinct from the soul, mind, or spirit. Therein lies the rub, when talking about somatic stem cells, or somatic cells in general. It is imperative to recognize that when using the term somatic, to describe stem cells, scientists and clinicians are talking about cells derived from the body, otherwise considered adult tissue. The NIH gives the definition of a somatic stem cell as:

Somatic (adult) stem cells—A relatively rare undifferentiated cell found in many organs and differentiated tissues with a limited capacity for both self renewal (in the laboratory) and differentiation. Such cells vary in their differentiation capacity, but it is usually limited to cell types in the organ of origin. This is an active area of investigation.

By definition these cells are not germline cells, or embryonic cells, but cells residing in adult tissue and organs with varying capacities for differentiation such as the mesenchymal cells shown in the accompanying image. Thus, a somatic cell can describe anything from a stem cell residing within your kidneys or bone marrow. Research and therapies directed at and utilizing somatic stem cells, do not involve the destruction of an embryo. In fact, there is active research aimed at utilizing one’s own biopsied tissue to create personalized somatic cell therapies, which brings us full circle to the meaning of the word somatic: “pertaining to (and derived from) the body”.

Advances in science and medicine have led to the development of new understandings of the mechanisms that underlie disease, as well as new treatment strategies. With these advances come litanies of new terms that can often lead to confusion and in some cases, contention. One of these ever advancing areas is the rapidly changing field of stem cell science. As our understanding of “stem” cells changes almost daily, consequently, so must our vocabularies. Failure to do so can often lead to misunderstandings in science, medicine, politics, and even religion.

Article contributed by Dr. O’Garcia, a somatic stem cell researcher and medical writer.

Sources:

1. Online etymology dictionary, www.etymonline.com

2. MyEtymology.com www.MyEtymology.com

3. NIH Stem Cell Basics. http://stemcells.nih.gov/Pages/Default.aspx

Note: The links to Google Translate in these articles include an icon that will allow you to hear the Greek or Latin pronunciation of the word.

- Details

The suffix [-schisis-] comes from the Greek word [σχίσις] and means "to tear" or "to separate". In Medicine today its meaning is that of "a cleft", a "split", or "a separation". The root term [gastr-] arises from the old Greek [gaster] meaning "belly"or "abdomen". In modern medical terminology it is used to mean "stomach", although its vernacular past still remains is some medical words.

In the case of [gastroschisis] the word refers to a congenital condition where the abdominal wall does not complete its normal closure and the baby is born with an incomplete abdominal wall allowing for the extrusion of abdominal viscera usually in a right paraumbilical position

Gastroschisis is rare with an incidence of 1 in every 10,000 births and is associated with younger mothers (under 20), smoking, and the use of cocaine.

Many cases of gastroschisis can be successfully treated with surgery.

Images courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Details

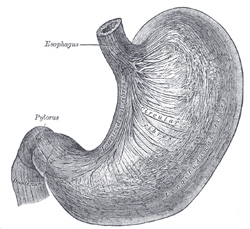

The root term [gastr-] arises from the old Greek [gaster] meaning "belly"or "abdomen". In modern medical terminology it is used to mean "stomach", although its vernacular past still remains is some medical words. Following are some used for this term:

- Gastritis: The suffix [-itis] means "infection" or "inflammation. Inflammation of the stomach

- Gastrotomy: The suffix [-(o)tomy] means "to cut" or "to open. Opening the stomach

- Gastrorrhaphy: The suffix [-(o)rrhaphy] means "to repair". Surgical repair of the stomach

- Gastroscope: The suffix [-(o)scope] means to an instrument used for viewing. To view the stomach

Here are a couple of examples of the root term [gastr-] used to mean "belly" or "abdomen":

- Gastroschisis: The suffix [-schisis] means "a cleft" or "a separation. An opening in the abdominal wall

- Gastrocnemius: The suffix [-(o)cnemius] is Greek and means "calf". The belly (like) muscles of the calf, the calf muscles

Source:

1. "Anatomy of the Human Body" Henry Gray 1918. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger

Original image courtesy of bartleby.com

- Details

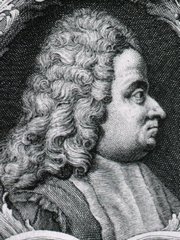

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Antonio Maria Valsalva

Antonio Maria Valsalva (1666 – 1723). Italian physician, surgeon, pathologist and anatomist, Antonio Maria Pini was born in the city of Imola. His father Pompeo Pini, a well-to-do goldsmith, adopted the family name Valsalva based on the location of his grandfather’s castle. Valsalva was well educated by Jesuits in mathematics, natural sciences and humanities, and continued his studies in Bologna, where he was trained in anatomy by Marcello Malpighi (1628 – 1694).

In 1687, at the age of 21, Valsalva received his Doctorate in Medicine and Philosophy. He was very dedicated to the practice of medicine, research and anatomical studies. Because of his anatomical knowledge he routinely used cadaver dissection in his clinical practice, advancing his knowledge as a pathologist. In 1694 he was appointed Professor of Anatomy at the University of Bologna.

One of his areas of interest was the anatomy of the hearing system, and his only known publication in 1704 is “De Aure Humana Tractatus” (The Study of the Human Ear) , where he described the ear as composed of the three regions known to us today: internal, middle, and external.

He described a maneuver to inflate the middle ear to erase deafness and increase suppuration caused by middle ear congestion. This is known today as the Valsalva maneuver used in medical practice, but also in deep sea diving and by pilots to clear the middle ear and balance the air pressure in the middle ear with that of the external environment. Today the cardiophysiological bodily response to Valsalva’s maneuver has been studied in detail.

Valsalva is responsible for the eponym “Eustachian tube” that refers to the muscular tube communicating the superior aspect of the pharynx (rhinopharynx) with the middle ear. He did dissections to study in detail the aorta and aortic valve, describing what today are known as the “sinuses of Valsalva”, a pocket-like dilation of the aortic valve between the aortic valve wall and the valve cusps (leaflets). Each of the coronary arteries arises from a sinus of Valsalva. Similar sinuses are found in the pulmonary valve.

During his studies of the mentally ill, Valsalva was of the opinion that madness was an organic disease and therefore mentally ill patients deserved humanitarian treatment, which was not the standard during his times.

One of his best students and pupil was Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682-1771) who, after the death of Valsalva in 1723, used some of his unpublished material to complement his own studies and publications.

Besides the Valsalva maneuver and the sinuses of Valsalva, there are other eponyms that honor this great anatomist:

• Valsalva Antrum or mastoid antrum is a cavity in the petrous portion of the temporal bone.

• Valsalva’s ligament attaches the pinna to the side of the head.

• Valsalva’s muscle: a band of vertical muscular fibers on the outer surface of the tragus of the ear, innervated by the temporal branch of the facial nerve

Sources:

1. “Seeing the Anatomy of Hearing: New Tools and Approaches Chart the Pathways Underlying How We Process and Integrate Sound” Laitman, JT The Anatomical Record (2006) 288A:323–324

2. “Antonio Maria Valsalva - Biographical Profile of a Pioneer on Otology” Meirelles, RC et al Int. Arch Otorhinolaryngol (2008)12: 2, 274-279

3. “The Valsalva manoeuvre and Antonio Valsalva (1666-1723)” J R Soc Med. (2006) 99(9): 448–451

4. “A short biography on the life of the dedicated anatomist –Valsalva” Kazi, R . J Postgrad Med (2004) 50:314-5

5. “Antonio Maria Valsalva (1666 – 1723)” Yale SH Clin Med Res (2005) 3(1): 35–38

Original image courtesy of the National Library of Medicine