Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 749 guests online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

- Written by: Theo Dirix

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Theo Dirix, Author and Taphophile

It is a truism that commemorations generate more attention for those being celebrated: since the quincentenary of 2014, the bibliography of the Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) exceeds 3000 entries, and counting (1). Has the moment also come when hoaxes in his biography, some that were refuted over fifty or a hundred years ago, finally cease to circulate? (2) The Quest for his Lost Grave is entering a second crucial phase, but will we ever find his remains and learn the cause of his death?

There is a consensus of opinion that his early work "De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem" marks the transition to empiric research. His academic career and his advancement to the position of family physician at the court of Charles V, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, and at that of his successor Philip II, are well documented. His last months, days and moments become clearer too but obstinate pranks survive. Indeed, there is absolutely no proof that he ever ran into the otherwise so well documented Inquisition (3).

Recently rediscovered letters are evidence that Vesalius left Spain as a pious pilgrim: a laissez-passer by Philip II, notes from the Spanish Embassy in Venice and even the letter of thanks written by the Custodian of the Holy Places in Jerusalem, which Vesalius was to hand over to Philip II (4) The latter unequivocally refutes the other prank that a shipwreck during his return was the cause of his death.

In the running up to the quincentenary, medical artist, artisan and curator, Pascale Pollier has launched a romantic quest for his grave. Keen to make his facial reconstruction, she went looking for his cranium. When the Embassy of Belgium in Athens incorporated her project in its public diplomacy, the Quest had become cross-disciplinary.

First some contradictions about his final resting place had to be cleared up. Prominent Vesalius biographers, Omer Steeno, Maurits Biesbrouck and Theodoor Goddeeris have provided the research that convincingly points to the catholic church of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Zakynthos. Unfortunately the church, constructed in 1488, disappeared under the rubble of a major earthquake in 1953. The trio also documented the fact that several eyewitnesses had visited his sepulchre and copied the epitaph, Christoph Fürer von Haimendorf being the first in August 1565. In May 1566 Reiner Solenander quotes a merchant from Nuremberg who had been travelling with Vesalius. Is he the goldsmith or jeweller, mentioned in other literature? The grave was also seen in 1586 by Jean Zuallart and Filippo Pigafetta. As early as 1574 Johannes Sambucus states that Vesalius was buried in Zakynthos and in 1603 he added the name of the church: “D.[omus] Mariae” (5).

Once the spot had been defined, the research team, now calling itself Vesalius Continuum (6), turned to archaeologists: Prof. Jan Driessen, Université Catholique de Louvain (UCL) and Director of the Belgian School in Athens, EBSA, and Apostolos Sarris, Deputy Director of the Institute for Mediterranean Studies - Foundation for Research and Technology, Hellas (IMS-FORTH).

In 2014, Dr. Sylviane Déderix (UCL/IMS-FORTH) checked the presumed location of the church through the spatial analysis of a Geographical Information System (GIS). Her comparison of historical maps with modern cartographic data shows that the ruins are to be found on the northwest corner of the intersection of Kolyva Street and Kolokotroni Street, partly below the asphalt and partly under private property.

During construction works on that exact spot, funerary slabs have already been excavated, and provide yet further proof that there was a cemetery at this location. A geophysical approach to the further examination of anomalies under the surface is imperative. With the necessary official permission and funding, a team of researchers could collect and process data through non-destructive methods such as ground penetrating radar (GPR) and electrical resistivity tomography (ERT). If this was to prove conclusive, a third phase of small-scale excavations in search of remains may follow.

One of the unearthed funerary slabs dates from the sixteenth century: it belonged to a certain Bevilaqua who was given the position of Public Physician in 1593. Vesalius is not the only traveller who has been buried there. Other high profile guests may be Bishop Balthassar, Maria Remondini (1698-1777) and the French philhellene and author of acclaimed travel books, Pierre-Augustin Guys who was buried in the church on 27 September 1799.

It is obvious that if human remains were exhumed genetic identification is a must. Vesalius Continuum turned to Dr. Maarten Larmuseau of the Laboratory of Forensic Genetics and Molecular Archaeology of the KULeuven. He is a Specialist in the genetic identification of old-DNA and will compare potential mitochondrial DNA and/or Y-chromosomes of remains in the Santa Maria delle Grazie with those of living relatives who are in direct maternal or pattern line. In the case of Vesalius, his direct descendants, and those of his wife, cannot contribute to the identification, but maternal relatives of his mother, Elisabeth Crabbé, can.

This romantic quest for the lost bones of the father of modern anatomy, which has turned into a cross-disciplinary search, ostensibly does not end in death, but rather in curiosity, understanding, beauty, love, passion, life (7).

You too can join in the adventure by contributing to the crowd funding campaign to sponsor the next step in the archaeological campaign: www.gofundme.com/VesaliusContinuum

Note: This article was originally published in Theo Dirix's blog. Published here with his permission. Theo Dirix is a Vesaliana contributor to Medical Terminology Daily.

Sources:

1. Maurits Biesbrouck upgraded Dr. Harvey Cushing’s list of publications on Vesalius to more than 3000 records: http://www.andreasvesalius.be , accessed 8 January 2017.

2. DIRIX, Theo: Andreas Vesalius and his hoaxes, con variazioni, in: Vesalius, Journal of the International Society of the History of Medicine, Vol. XXII, nr. 1, June 2016, Special Issue, Proceedings of A Tribute to Andreas Vesalius, Padua, Italy - December 2015, pp. 103 - 111.

3. The source is post-mortem gossip spread in January 1565 by the French diplomat, Hubertus Languetus, in a note of 24 lines opening with: “rumour has it”. See: BIESBROUCK, Maurits, Theodoor GODDEERIS, Omer STEENO. ‘Post Mortem’ Andreae Vesalii (1514-1564), Deel I. De laatste reis van Andreas Vesalius en de omstandigheden van zijn dood), in: A.Vesalius, nr. 3 september 2015, Alfagen, Leuven, pp 154-161.

4. In total four letters have been discovered by José Baron Fernandez in the archives of Simancas, described and published since 1965, brought back to light by Steeno, Biesbrouck and Goddeeris.

5. Primary sources about the epitaphs are shown in:https://vimeo.com/album/4256560/video/190461188, accessed 15/01/2017

6. Within the initial ad hoc organising committee of the Vesalius Continuum Conference in September 2014 in Zakynthos, medical artist Pascale Pollier and the author, then Consul at the Embassy of Belgium in Athens, formed the Search team.

7. Closing lines of the “Conclusion, to be continued” in: DIRIX, Theo, In Search of Andreas Vesalius, The Quest for the Lost Grave, LannooCampus, Leuven, 2014, p.140.

- Details

- Written by: Fernanda Cortes, DDS, MSc

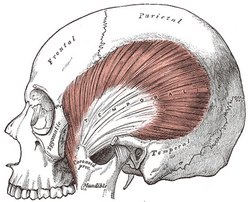

The temporal fascia (Lat:Fascia Temporalis) is thick and strong muscular (deep) fascia that covers the external surface of the temporal muscle.

It originates on a curved line formed by the posterosuperior part of the zygomatic bone, the temporal line of the frontal bone, the upper temporal line of the temporal bone and the area between both upper and lower temporal lines. It is divided in two laminae: superficial and deep which have insertion on the zygomatic arch. The deep portion provides insertion to the temporal muscle (1,2). The superficial layer is part of the epicraneal aponeurosis (3).

The two layers of the temporal fasica have separate arterial and venous blodd supply.

Article written by: Maria F. Cortés, DDS, MSc.

Images from:

Fig 1. Public domain, by Henry Vandyke Carter, MD - Gray's Anatomy, 1918

Sources:

1. “Anatomía humana” V.2. Latarjet- Ruiz Liard, 4ª ed. 6ª reimp. 2008 Médica Panamericana, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

2. “Anatomía humana: descriptiva, topográfica y funcional. Tomo 1. Cabeza y Cuello, Rouviere H – Delmas A, 11° ed. 2005 MASSON, S.A., Barcelona, Spain.

3. "Anatomy of the temporalis fascia" Wormald PJ, Alun-Jones T. J Laryngol Otol. 1991 Jul;105(7):522-4.

- Details

- Written by: Fernanda Cortes, DDS, MSc

The temporal muscle (Lat:Temporalis) is a bilateral muscle located on the side of the head. It belongs to a subgroup of head muscles called Masticatory Muscles, named after their function elevating the mandible to produce the mandible movements (1,2). Masticatory muscles are four per side: Temporalis, Masseter, Pterygoideus medialis and Pterygoideus lateralis (1,2).

The temporalis muscle is a fan-shaped muscle which occupies the temporal fossa from which its fascicles (fibers) converge to the coronoid process of the mandible. Classic description for this muscle recognizes three main muscular bodies (anterior, midle, and posterior) originated from the temporal fossa up to the lower temporalis line and the temporalis fascia, fascicles which descend through the inner part de the zygomatic arch converging to be inserted on the coronoid process of the mandible, its temporalis crest and anterior margin of the mandibular branch through thick tendons (1,2).

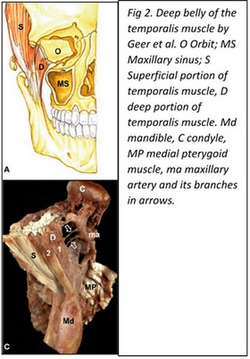

In 1996 Dunn et al. (3) reported the discovery of a so far unknown masticatory muscle called the “sphenomandibularis”, originated from the greater wing of the sphenoid bone medial to the temporalis muscle and descends on an oblique (lateral and slightly posterior) fashion reaching distally the coronoid process of the mandible. This muscular portion has been recognized as the “deep belly of the temporalis muscle” and has been described by several authors since then (4,5,6,8). The importance that has been given to this particular bundle lies on the fact that its medial insertion can reach a close relationship to the foramen rotundum, place of emergency from the cranium of the maxillary nerve, which has been hypothesized, could lead to eventual alteration of this nerve if it got trapped by this part of the muscle (6, 7).

The temporalis muscle receives innervation fundamentally from branches of the mandibular nerve: Deep temporal nerve (N. temporalis profundus)through its anterior middle and posterior branches.

The temporalis muscle is covered by a thick fascia layer: the temporalis fascia.

Article written by: Maria F. Cortés, DDS, MSc.

Images from:

Fig 1. Public domain, by Henry Vandyke Carter, MD - Gray's Anatomy, 1918

Fig 2. Geers C, Nyssen-Behets C, Cosnard G, Lengelé B. The deep belly of the temporalis muscle: an anatomical, histological and MRI study. Surg Radiol Anat. 2005 Aug;27(3):184-91. Epub 2005 Apr 9

Sources:

1. “Anatomía humana” V.2. Latarjet- Ruiz Liard, 4ª ed. 6ª reimp. 2008 Médica Panamericana, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

2. “Anatomía humana: descriptiva, topográfica y funcional. Tomo 1. Cabeza y Cuello, Rouviere H – Delmas A, 11° ed. 2005 MASSON, S.A., Barcelona, Spain.

3. Dunn GF, Hack GD, Robinson WL, Koritzer RT. Anatomical observation of a craniomandibular muscle originating from the skull base: the sphenomandibularis. Cranio. 1996 Apr;14(2):97-103; discussion 104-5.

4. Shimokawa T, Akita K, Soma K, Sato T. Innervation analysis of the small muscle bundles attached to the temporalis: truly new muscles or merely derivatives of the temporalis? Surg Radiol Anat. 1998;20(5):329-34.

5. Akita K, Shimokawa T, Sato T. Aberrant muscle between the temporalis and the lateral pterygoid muscles: M. pterygoideus proprius (Henle). Clin Anat. 2001 Jul;14(4):288-91.

6. Schön Ybarra MA, Bauer B. Medial portion of M. Temporalis and its potential involvement in facial pain. Clin Anat. 2001;14(1):25-30.

7. Fuentes E, Llanos S, Gómez R, Llanos P, Llanos F, Cortés-Sylvester MF, Solaria P, Melian A, Asfura J, Santos M, Zamorano E. Discovery of deep temporalis muscle belly close to maxillary nerve in a patient with trigeminal neuralgia: hypothesis of muscular compression and case report treated by Botox® Onabotulinum toxin tipe-A. Chirurgia 2016 June;29(3):99-102

8. Geers C, Nyssen-Behets C, Cosnard G, Lengelé B. The deep belly of the temporalis muscle: an anatomical, histological and MRI study. Surg Radiol Anat. 2005 Aug;27(3):184-91. Epub 2005 Apr 9.

- Details

We would like to welcome María Fernanda Cortés DDS, MSc. as a contributor to Medical Terminology Daily.

Dr. Cortés has a degree in Dentistry and is a Specialist in Dentomaxilofacial Radiology. She also has a Master’s degree in Temporomandibular disorders and orofacial pain.

Currently she is a lecturer of Human Anatomy at the Faculty of Dentistry of the Finis Terrae University. She also collaborates as a Postgraduate teacher for students of the “Anatomical Bases of Normal Imaging” diploma program at the Medical school of the same university.

Dr. Cortés has her own private practice in Santiago, Chile.

Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc is proud to have Dr. Cortés as a contributor to "Medical Terminology Daily" and as a consultant to our team.

- Details

Today I received the bust of Andreas Vesalius which will be displayed in my office in a place of honor.

This bust is a small version of a bronze bust made by the Belgian artist Pascale Pollier, who is a contributor to "Medical Terminology Daily". Copies of this original bronze bust can be found is different libraries and museums around the world. Pascale, along with Theo Dirix, Dr. Sylviane Déderix, and others are on a quest to find the cemetery where Andreas Vesalius was buried in the island of Zakynthos in Greece. Eventually, the final quest is to find the body of this illustrius anatomists.

To fund this private research Pascale and other artists have donated their work to a GoFundMe page whose objective is to raise €9,900, roughly US$10,800. You can reach the GoFundMe page here.

This bust that sits in my office today is the sixth in a run of twelve copies. If you go to the GoFundMe page you can opt to aquire other artistic works or one of the last copies of this bust. To acquire the bust there is a minumum required donation of US$350.

As of this publication, the research is 51% funded. We need your help to achieve our goal!!

- Details

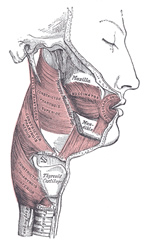

The [buccinator] muscle is a flat, thin quadrilateral muscle, that closes the space between the maxillary bone superiorly and the mandible inferiorly. It forms the side of the face and is the main muscular component of the “cheeks”. Etymologically [buccinator] means "trumpeter".

The superior and inferior boundaries of the muscle are the external surfaces of the alveolar processes of the maxilla and mandible on its posterior region, related to the posterior three molars. The posterior boundary is the anterior border of the pterygomandibular raphe, where posteriorly the middle pharyngeal constrictor also attaches. Anteriorly, its fibers appear to continue with the orbicularis oris muscle, but this is not so, as these two muscles (orbicularis oris and buccinator) are separate.

The fibers of the buccinator muscle are divided into three groups: the horizontal group continues anteriorly horizontally. The superior fibers have an anteroinferior direction and converge toward the angle of the mouth. The inferior fibers have an anterosuperior direction. These fibers appear to be continuous with the orbicularis oris, although they terminate in the mucosa, skin and some intermix with the muscular fibers of the orbicularis oris.

The buccinator muscle is covered by the buccopharyngeal fascia, and is in relation by its superficial surface and posteriorly, with a mass of fat (Bichat’s fat pad or suctorial pad), which separates it from the ramus of the mandible, the masseter, and a small portion of the temporalis muscle.

The parotid duct (Stensen’s duct) pierces the buccinator muscle opposite the second molar tooth of the maxilla.

The buccinator muscle receives innervation from the temporofacial and cervicofacial branches of the facial nerve (7th cranial nerve)

Sources:

1. “Gray’s Anatomy” Henry Gray, 1918

2. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8th Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

3. "Gray's Anatomy" 38th British Ed. Churchill Livingstone 1995

Image in Public Domain, by Henry Vandyke Carter, MD - Gray's Anatomy, 1918