Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 914 guests online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

UPDATED: The definition of hernia is "the protrusion of a deep structure through a superficial weakness of defect".

Herniation has many etiologies, but in all cases a weakness of a superficial containing wall (usually layered) or a normal or abnormal opening (defect) must be present. A true hernia usually has a deep sac or hernia sac which contains the herniated viscus or viscera. Repair of a hernia is called a hernioplasty or a herniorrhaphy.

Although with exceptions, a herniation with only weakening of the walls and no hernia sac can be called a "prolapse", the suffix for prolapse (or hernia sometimes) is [-ocele].

• Omphalocele: From the Greek [omphalos] meaning "umbilicus", an omphalocele is a herniation through the umbilicus.

• Cystourethocele: A prolapse of the urinary bladder and urethra with a weakened vaginal wall

There are also "internal' hernias, between bodily compartments. Examples are:

• Esophageal hiatus hernia: Known as a "hiatal hernia", this hernia is a protrusion of a peritoneal sac with abdominal visceral content into the thorax.

• Perineal hernia: The protrusion of abdominopelvic content into the perineal region through a defect in the pelvic diaphragm (levator ani)

A hernia is usually named for the superficial region where it protrudes. An example of this would be a femoral hernia, which starts as an abdominopelvic extrusion, but it ends protruding in the area of the thigh (femoral region). Abdominal or ventral hernias are named according to the abdominal region through which they protrude.

in older times the word "rupture" was used as a synonym for "hernia", as can be seen in a letter written by Dr. Ephraim McDowell in 1829. The image shows an example of an indirect inguinal hernia.

Original Image public domain courtesy of: nih.gov.

- Details

UPDATED: The word [pecten] originates from the Latin [pectine] meaning "to comb", the adjective [pectinate] means "resembling a comb". The term denotes structures that have well-formed parallel shapes, such as the pectinate muscle of the heart. The pectinate muscle can be clearly seen in the internal aspect of the atrial appendages. (see image, pointer "B")

The term [pecten] meaning "comb" is an old word used for the superior aspect of the pubic bone (os pubis) where the pectineus muscle attaches. The root term [-pectin-] can be seen then in terms such as the iliopectineal line, and the pectineal ligament, also known as "Cooper's ligament".

The origin of the use of the term [pecten os pubis] to denote the area of attachment of the pectineus muscle to the bony ridge in the superior aspect of the pubic bone is obscure, but the pectineus muscle has well-marked parallel striations resembling a comb.

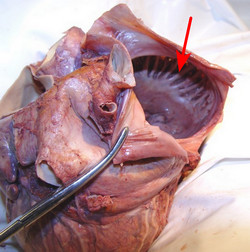

The image shows a human heart where the right atrium has been opened. The red arrow points to the pectinated muscle characteristic of the right atrial appendage (right auricle). Keep in mind that the distribution and shape of the muscle of the left atrial appendage is completely different.

Note: The links to Google Translate include an icon that will allow you to hear the pronunciation of the word.

- Details

[Infundibulum] is a Latin word and it means "funnel". The plural form is [infundibula]. Variations of the word include [infundibuliform] meaning "with the shape or form of a funnel], and [infundibular] meaning "pertaining to a funnel". This word is widely used in human anatomy and embryology:

- Infundibuliform fascia: Funnel-shaped portion of the transversalis fascia that is directed toward and forming the internal inguinal ring.

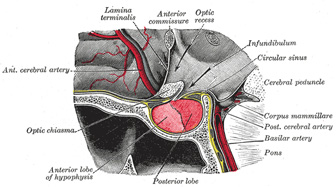

- Hypophyseal infundibulum: An inferior extension of the hypothalamus forming a funnel-shaped stalk connected to the hypophysis or pituitary gland. (see image)

- Cystic infundibulum: The funnel-shaped portion of the gallbladder

- Ethmoidal infundibulum: a funnel-shaped extension of the middle meatus of the ethmoid bone, etc.

- Uterine infundibulum: Refers to the funnel-shaped distal opening of the uterine tube

The term infundibulum is also found in heart anatomy. It refers to funnel-shaped extensions of the cardiac chambers. This is well-illustrated by both the cone-like right and left ventricular outflow tracts toward the semilunar valves (aortic and pulmonary). In the case of the atrioventricular valves (tricuspid and mitral) there is also described an infundibular region. In all cases, these funnel-shaped regions allow for smooth, non-turbulent blood flow towards their respective valves.

Word suggested by: J. Estrada. Original image in the public domain, courtesy of bartleby.com

- Details

The term [larynx] originates from the Greek [λάρυγξ] meaning "upper windpipe or throat". Known vernacularly as "Adam's apple" or the "voice box" (not proper clinical terms), the larynx is the organ of phonation, and one of the organs found in the cervical visceral compartment. It is found immediately superior to the trachea, and anterior to the pharynx and esophagus.

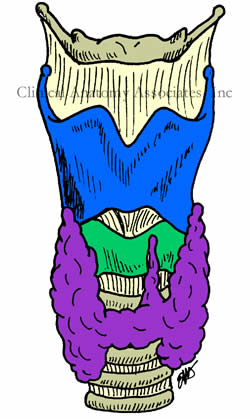

It is formed by nine cartilages, three of which are median and single (epiglottis, thyroid, and cricoid cartilages), the rest being paired (arytenoid, corniculate, and cuneiform cartilages). In the accompanying image, the thyroid cartilage is depicted in blue, and the cricoid cartilage in green.

Within the larynx is a pair of musculomembranous folds, the vocal cords, which are innervated by the recurrent laryngeal nerves, branches of the Xth cranial nerve, also known as the vagus nerve.

The thyroid gland (in purple) is related to the inferior aspect of the larynx. The gland receives its name from the thyroid cartilage of the larynx, as the Greek term [θυροειδής] (thyreoeidís) means "in the shape of an oblong-shield".

It was Andrea Vesalius who named the cricoid cartilage because of its shape. The Greek term [κρικοειδή] (krikoeidí) refers to a structure "shaped like a ring". The cricoid cartilage is a complete ring, and thus is different from the incomplete or "C" shaped rings of the trachea.

Image property of CAA Inc. Artist: Dr. Miranda

- Details

Dr. Maurits Biesbrouck was born in Roeselare (Belgium) on February 15th, 1946, studied medicine at the Catholic University Leuven and became a MD in 1972. He devoted his professional career to clinical pathology (City Hospital Roeselare) and transfusion medicine He became adjunct medical director of the Dienst voor het Bloed (Brussels) and was the president-founder of the Scientific Association Transfusion in Flanders (WVTV).

Having a lifelong interest in Andreas Vesalius he translated the first book of the De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem into Dutch, compiled an annually updated Vesalius-bibliography and wrote many articles on his life and works, many as a co-author with Omer Steeno (Leuven, Belgium) and Theodoor Goddeeris (Kortrijk, Belgium). For the moment he is working on an overview of the editions of Vesalius’s works. See www.andreasvesalius.be.

Thanks to Dr. Bisbrouck for collaborating with "Medical Terminology Daily" with the article "Andreas Vesalius' Fatal Voyage to Jerusalem", a 2016 updated version of an original presentation at the 2014 Vesalius Continuum Meeting in Zakynthos, Greece.

He was part of the research team that uncovered the "false Vesalius postage stamps".

- Details

By Maurits Biesbrouck, MD. Continued from "Andreas Vesalius’s fatal voyage to Jerusalem (5)".

For the first page of this article, click here.

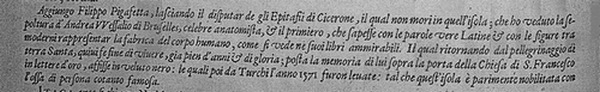

Passage in Abraham Ortelius’s Teatro del Mondo with Pigafetta’s report on Vesalius’s burial place. In Italian

“Leaving aside the discussion on the epitaph of Cicero, who did not die on this island [Zakynthos], I, Filippo Pigafetta, add having seen the grave of Andreas Vesalius from Brussels, famous anatomist and the first one to render in appropriate Latin wordings and accompanied with modern illustrations the fabric of the human body, as can be seen in his marvelous books. While returning from a pilgrimage to the Holy Land he ended his life here after glorious years. An inscription to his memory was placed above the door to the church of Saint Franciscus, in golden letters on black velvet, that was taken away by the Turcs in 1571. Thus this island was ennobled likewise by the bones of such famous persons” (16).

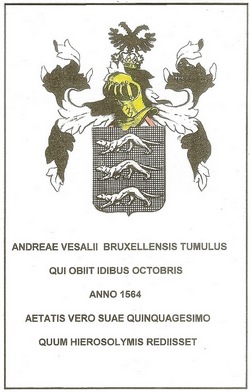

Reconstruction of Vesalius’ epitaph

by Theodoor Goddeeris (2012)

Pigafetta saw the grave in July 1586, almost at the same time as Jean Zuallart, but he may have seen it yet in 1568, on his way to Cyprus, or during his travelling to Egypt and Mount Sion in 1576-1577. When his information dates from 1568, or was based on reliable sources later on, then the Turcs could have taken two inscriptions: his epitaph and a plaque at the entrance of the church (17).

The church S. Maria delle Grazie

As far as is known, Fürer, Zuallart, and Pigafetta were the only three travellers to Jerusalem, to have seen Vesalius’s grave in the S. Maria delle Grazie with their own eyes. Thanks to them we are sure that Vesalius was buried in that church, built in 1488. Regrettably, it was destroyed on October 18th 1840 by a severe earthquake. It was then rebuilt, but moved a few meters inland. In 1893 the church was again destroyed by an earthquake. This time it was not restored, and the rubble was used by the fishermen along the coast to rebuild their houses, as told by Barbiani (18).

Vesalius’s epitaph

So Fürer saw Vesalius’s epitaph before it was stolen, but he gave an incorrect description of Vesalius’ coat of arms on it. Anyway, it follows that Vesalius’ grave was indeed at this church, and that he must have been buried there and not by the side of a road somewhere. An effort was immediately made to give him a worthy burial place. The epitaph with the coat of arms, which was already present so soon after his death, is proof of this. The people of Zakynthos were well aware of who this person was. To correct the errors in the epitaph and in the coat of arms as well, some years ago, Dr. Theodoor Goddeeris, made a graphic reconstruction of both.

Conclusions

I can summarize with four conclusions (19):

1° Andreas Vesalius' trip to Jerusalem had nothing to do with the Inquisition: he went to Jerusalem for religious reasons, and the King took the opportunity to send with him his financial support for the Holy Places, as he used to do.

2° Vesalius did not die in a shipwreck. He died most probably of a combination of exhaustion and illness.

3° He was not buried on some desolate spot, but in the church Santa Maria delle Grazie. His remains are not yet found, however. (see here for additional information on the search for Vesalius' grave).

4° His grave had an epitaph (and we know exactly what it said and looked like).

Personal note: My sincere thanks to Dr. Maurits Biesbrouck for contributing this article to "Medical Terminology Daily". His clear and factual analysis gives us an insight on the last months of Andreas Vesalius' life and the problems that eventually led to his death on Zakynthos, Greece. I am proud to have been one of the many international attendees to the 2014 meeting in the island of Zakynthos where I saw Dr. Biesbrouck deliver the presentation and research on which this article is based. Dr. Miranda.

Sources and author's comments:

16. Teatro del Mondo di Abrahamo Ortelio: da lui poco inanzi la sua morte riveduto, e di tavole nuove, et commenti adorno, e arricchito con la vita dell’Autore. Traslato in Lingua Toscana dal Sigr. Filippo Pigafetta, in Anversa, si vende nella Libraria Plantiniana, 1608 and 1612.

17. Maurits BIESBROUCK, Theodoor GODDEERIS, Omer STEENO. ‘Post Mortem Andreae Vesalii (1514-1564). Deel I: De laatste reis van Andreas Vesalius en de omstandigheden van zijn dood’ [After Vesalius’ Death: The Last Travel of Andreas Vesalius and the Circumstances of his Death] and ‘Deel II: Het graf van Andreas Vesalius op Zakynthos’ [Vesalius’ Grave in Zakynthos] in A. Vesalius, 2015, 27 (no. 3): 154-161 and (no. 4): 193-200, ill.

18. Nicolas Ant. BARBIANI, O André Vésale kai è proodos tès anatomias [Andreas Vesalius and the evolution of anatomy] – L’évolution de l’anatomie et André Vésale, Athens, 1953, 32 pp., ill.; in Greek with a French summary on pp. 7-8.

19. For more details see the papers mentioned in ref. 1.