Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 749 guests online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

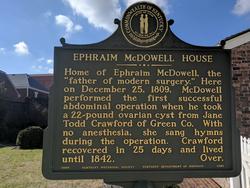

In 2013 I wrote a short biography of Dr. Ephraim McDowell (1771- 1830) for the sidebar on this blog entitled “A Moment in History”. While researching the life of this illustrious surgeon I learned that his house is now a National Historic Landmark and has been transformed into a museum in the city of Danville, Kentucky. It took me almost four years but on Sunday February 19, 2017 I was able to go visit this place. Following is a series of articles and pictures of this visit.

The house itself was built in the 1790’s and most of it has been restored and lovingly maintained by the city, the Kentucky Medical Association, a Board of Directors, and a group of volunteers that work as docents giving tours of the house.

The following is an edited excerpt of Wikipedia on the McDowell House:

“After McDowell's death in 1830 the house was sold. It was the home of a Centre College president for a short time. Later the entire area became a slum and tenement property. The house deteriorated badly. Dr. August Schachner, of Louisville, led the efforts to buy the house for restoration. In 1921 he visited the house. "Since our last visit, the house has continued its downward course until it has reached a point where it now seems almost beyond redemption”. The room in the rear of the corresponding front room on the second floor,"(the operating room) "which is on a lower level by several feet, is used as a dump for the ashes from the grates of the rooms on the second floor."

The Kentucky Medical Association bought the house in 1935 and deeded it to the state of Kentucky, who had it restored by the Works Progress Administration (WPA). It was dedicated on May 20, 1939. In 1948, Kentucky returned the property to the Kentucky Medical Association.

The Kentucky Pharmaceutical Society restored the Apothecary Shop in the late 1950s with help from the Eli Lily Foundation. It was furnished by the Pfizer Laboratories. It was dedicated and presented to the Kentucky Medical Association on August 14, 1959.”

The house is located at 125 South Second Street, Danville, KY 40422. It is a white two-story wooden structure considered to be large for the time. To the right side stands a small one-story brick structure, the apothecary, where Dr. McDowell would provide medicine for his patients and others. To the left is the patio and garden where Dr. McDowell would grow medicinal plants for the apothecary. On the garden front there is a large two-sided plaque that reads:

Front of the plaque at the Ephraim McDowell House

“Home of Ephraim McDowell, the “father of modern surgery.” Here on December 25, 1809 McDowell performed the first successful abdominal operation when he took a 22-pound ovarian cysts from Jane Todd Crawford of Green Co. With no anesthesia, she sang hymns during the operation. Crawford recovered in 25 days and lived until 1842”

Back of the plaque at the Ephraim McDowell House

“Built in three stages. Brick ell, or single-story wing, built 1790s. McDowell purchased house in 1802 and added front clapboard section c.1804. Rear brick office and formal gardens added in 1820. House sold when McDowell dies in 1830. 1n 1930s, Ky. Med. Assoc. bought house; restored by WPA. House dedicated on May 20, 1939. Now a house museum”

- Details

This is a series of articles on depression published as a community service. The information in these articles follow our Privacy and Security Guidelines and cannot be construed as medical guidance. For additional information and counseling, consult with your physician or the appropriate health care professional of your choice. You can also find information on Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) here. For the initial article on this series click here.

This article could also be entitled:

What is the difference between unipolar and bipolar depression?

Mood is a range of emotions that describe how we "feel" at a particular point in time. Mood is called a "visceral" (gut-like) sensation and is difficult to describe. It is a sensation dependent on a group of deep brain structures known as the limbic system.

Being a spectrum, there are two ends or "poles" to the range. An one end we have the major depressive mood of darkness, despair, and loathing of one's self. At the other end or "pole" we have the manic feeling of happiness, feeling "high", with extreme irritability and quick actions without measuring potential consequences.

An MDD patient that is "stuck" at the dark end of the spectrum, is said to be "unipolar", as the Latin word unus and uni- mean "one". The patient is always at one pole, therefore "unipolar".

Some depression patients have mood swings going from one end of the mood spectrum to the other. Since the medical prefix [bi-] means "two", these patients are said to have a "bipolar" type depression.

Some authors comment that there is not really a true unipolar depression for even unipolar depression patients move within the mood spectrum as their pathology evolves with treatment.

Experience tells us that as a depression patient starts to come out of their neurologically depressed state they may begin to show anxiety. This is easily treated by adding a secondary prescription course of right-sided low frequency treatment of TMS. As you go through your TMS Therapy treatment you may expect your prescription and dosage to change to accommodate your development towards a life without depression

References:

1. Barbee, J. G. (1998). Mixed symptoms and syndromes of anxiety and depression: Diagnostic, prognostic, and etiologic issues. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 10:15–29.

2. Regier, D. A., Rae, D. S., Narrow, W. E., Kaelber, C. T., & Schatzberg, A. F. (1998). Prevalence of anxiety disorders and their comorbidity with mood and addictive disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry. Supplement, 34: 24–28.

- Details

This is a series of articles on depression and published as a community service. The information in these articles follow our Privacy and Security Guidelines and cannot be construed as medical guidance. For additional information and counseling, consult with your physician or the appropriate health care professional of your choice. You can also find information on Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) here. For the initial article on this series click here.

Medication

SSRIs and SNRIs

Tricyclics

MAOIs

FDA warning on antidepressants

Psychotherapy

Electroconvulsive therapy

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

The most common treatments for depression are medication and psychotherapy. Drugs are used to treat the primary disorder, but they can be strengthened with augmentation medication. Some patients take so many different medicines that they refer to them as their daily "cocktail". By their own nature drugs are unspecific in that they alter and influence the whole body. Depression drugs have a number of side effects. The side effects of some drugs is a listing of potentially dangerous events, as can be seen in this video.

To illustrate the side effects, following is a list of the side effects listed in the packaging of one of these modern less-side-effect drugs as listed by the manufacturer:

• Symptoms of aggression

• Irritability

• Panic attacks

• Extreme worry

• Restlessness

• Acting without thinking

• Abnormal excitement

• Thoughts of suicide

• If present, glaucoma symptoms may worsen

• May cause liver damage, and may not be taken if the patient has liver disease

• Alcohol consumption may increase some serious side effects

• The patient may feel drowsy

• May cause high blood pressure, dizziness, or lightheadedness

Medication

Antidepressants primarily work on brain neurotransmitters, especially serotonin and norepinephrine. Other antidepressants work on the neurotransmitter dopamine. Scientists have found that these particular chemicals are involved in regulating mood, but they are unsure of the exact ways that they work.

SSRIs and SNRIs

Some of the newest antidepressants are called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), escitalopram (Lexapro), paroxetine (Paxil), and citalopram (Celexa) are some of the most commonly prescribed SSRIs for depression. Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are similar to SSRIs and include venlafaxine (Effexor) and duloxetine (Cymbalta).

SSRIs and SNRIs tend to have fewer side effects than older antidepressants, but they do sometimes produce headaches, nausea, jitters, or insomnia when people first start to take them. These symptoms tend to fade with time. Some people also experience sexual problems with SSRIs or SNRIs, which may be helped by adjusting the dosage or switching to another medication.

One popular antidepressant that works on dopamine is bupropion (Wellbutrin). Bupropion tends to have similar side effects as SSRIs and SNRIs, but it is less likely to cause sexual side effects. However, it can increase a person's risk for seizures.

Tricyclics

Tricyclics are older antidepressants. Tricyclics are powerful, but they are not used as much today because their potential side effects are more serious. They may affect the heart in people with heart conditions. They sometimes cause dizziness, especially in older adults. They also may cause drowsiness, dry mouth, and weight gain. These side effects can usually be corrected by changing the dosage or switching to another medication. However, tricyclics may be especially dangerous if taken in overdose. Tricyclics include imipramine and nortriptyline.

MAOIs

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are the oldest class of antidepressant medications. They can be especially effective in cases of "atypical" depression, such as when a person experiences increased appetite and the need for more sleep rather than decreased appetite and sleep. They also may help with anxiety, panic attacks, and other specific symptoms.

However, people who take MAOIs must avoid certain foods and beverages (including cheese and red wine) that contain a substance called tyramine. Certain medications, including some types of birth control pills, prescription pain relievers, cold and allergy medications, and herbal supplements, also should be avoided while taking an MAOI. These substances can interact with MAOIs to cause dangerous increases in blood pressure. The development of a new MAOI skin patch may help reduce these risks.

MAOIs can also react with SSRIs to produce a serious condition called "serotonin syndrome," which can cause confusion, hallucinations, increased sweating, muscle stiffness, seizures, changes in blood pressure or heart rhythm, and other potentially life-threatening conditions. MAOIs should not be taken with SSRIs.

Sometimes stimulants, anti-anxiety medications, or other medications are used together with an antidepressant, especially if a person has a co-existing illness. However, neither anti-anxiety medications nor stimulants are effective against depression when taken alone, and both should be taken only under a doctor's close supervision.

FDA warning on antidepressants

Despite the relative safety and popularity of SSRIs and other antidepressants, studies have suggested that they may have unintentional effects on some people, especially adolescents and young adults. In 2004, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) conducted a thorough review of published and unpublished controlled clinical trials of antidepressants that involved nearly 4,400 children and adolescents. The review revealed that 4 percent of those taking antidepressants thought about or attempted suicide (although no suicides occurred), compared to 2 percent of those receiving placebos.

This information prompted the FDA, in 2005, to adopt a "black box" warning label on all antidepressant medications to alert the public about the potential increased risk of suicidal thinking or attempts in children and adolescents taking antidepressants. In 2007, the FDA proposed that makers of all antidepressant medications extend the warning to include young adults up through age 24. A "black box" warning is the most serious type of warning on prescription drug labeling.

The warning emphasizes that patients of all ages taking antidepressants should be closely monitored, especially during the initial weeks of treatment. Possible side effects to look for are worsening depression, suicidal thinking or behavior, or any unusual changes in behavior such as sleeplessness, agitation, or withdrawal from normal social situations. The warning adds that families and caregivers should also be told of the need for close monitoring and report any changes to the doctor. The latest information from the FDA can be found on their website.

Results of a comprehensive review of pediatric trials conducted between 1988 and 2006 suggested that the benefits of antidepressant medications likely outweigh their risks to children and adolescents with major depression and anxiety disorders.

Psychotherapy

Two main types of psychotherapies—cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT)—are effective in treating depression. CBT helps people with depression restructure negative thought patterns. Doing so helps people interpret their environment and interactions with others in a positive and realistic way. It may also help you recognize things that may be contributing to the depression and help you change behaviors that may be making the depression worse. IPT helps people understand and work through troubled relationships that may cause their depression or make it worse.

For mild to moderate depression, psychotherapy may be the best option. However, for severe depression or for certain people, psychotherapy may not be enough. For example, for teens, a combination of medication and psychotherapy may be the most effective approach to treating major depression and reducing the chances of it coming back. Another study looking at depression treatment among older adults found that people who responded to initial treatment of medication and IPT were less likely to have recurring depression if they continued their combination treatment for at least 2 years.

Electroconvulsive therapy

For cases in which medication and/or psychotherapy does not help relieve a person's treatment-resistant depression, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may be useful. ECT, formerly known as "shock therapy," once had a bad reputation. But in recent years, it has greatly improved and can provide relief for people with severe depression who have not been able to feel better with other treatments.

Before ECT begins, a patient is put under brief anesthesia and given a muscle relaxant. He or she sleeps through the treatment and does not consciously feel the electrical impulses. Within 1 hour after the treatment session, which takes only a few minutes, the patient is awake and alert.

A person typically will undergo ECT several times a week, and often will need to take an antidepressant or other medication along with the ECT treatments. Although some people will need only a few courses of ECT, others may need maintenance ECT—usually once a week at first, then gradually decreasing to monthly treatments.

ECT may cause some side effects, including confusion, disorientation, and memory loss. Usually these side effects are short-term, but sometimes they can linger. Newer methods of administering the treatment have reduced the memory loss and other cognitive difficulties associated with ECT.

FDA cleared in 2008, Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) is one of the most promising therapies in the arsenal against depression. One of the key advantages of TMS is that while medical treatment is generalized, affecting the whole body, TMS targets the area of the brain most related in cortical control of mood changes, the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. With minimal and very localized side effects, repetitive TMS (rTMS) treatment has proven very effective.

Next: Depression and anxiety

- Details

HAPPY VALENTINE'S DAY!

For years I tried to understand from where did the classical Valentine's Day heart shape(❤) came. It was not until I was observing a human heart from the posteroinferior aspect, the diaphragmatic surface of the heart that I realized I was looking at it! You see, in the early days of anatomy, the heart was considered to be the ventricles only. This lead to consider the chambers at the "entrance" to the heart to be called "atria". This image of the heart is only valid if you make abstraction of the atria and look at the ventricles only.

Of course, there is a view of the heart, a cross section where you can see all four chambers of the heart. This four-chambered view is called by some the "Valentine's view".

I like my interpretation better. At least now you know that when you draw a [❤] you are being anatomically correct! It is only the ventricles of the heart in a posteroinferior view. Happy Valentine's Day! Dr. Miranda

Image property of:CAA.Inc.Photographer:David M. Klein

- Details

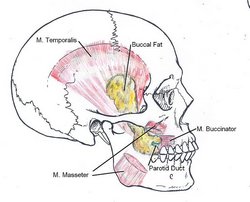

The [buccal fat pad] is dense, fatty trigone-shaped pad that is located in the cheek. It is formed by several connective-tissue encapsulated smaller fat pads. It covers partially the posterior aspect of the buccinator muscle, and is found deep to the anterior portion of the masseter muscle. Also known as “Bichat’s fat pad”, it was first described by Marie-François Xavier Bichat in 1802. It is also known as the suctorial fat pad and it helps in the suction process for breast feeding in infants, although because of its location it is also said to help in the gliding motion of the masticatory and facial expression muscles. The buccal fat pad is well developed in newborns and is not as evident in most adults.

Its anatomical description varies according to the authors, but it has a main body and three extensions, namely the anteromalar (anterior), pterygomaxillary (pterygoid), and temporal (posterotemporal) extensions. The blood supply to the buccal fat pad is by way of the anterior deep temporal, buccal, and posterior superior alveolar arteries.

Excessive development of this fat pad can lead to cosmetic surgery to eliminate, or at least reduce its size. This procedure is known in many countries as a “bichectomy”, Bichatectomy” of “cheek reduction surgery”, in some cases this procedure can be performed intraorally.

The buccal fat pad can also be used in maxillofacial reconstructive surgery, as well as the repair of skull base defects. When dissecting the buccal fat pad, care must be taken because of the relation of this structure with the parotid duct, the parotid gland, and branches of the facial nerve

Sources:

1. “Anatomy of the buccal fat pad and its clinical significance” Jackson, IT Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 06/1999, Volume 103, Issue 7

2. "A review of the gross anatomy, functions, pathology, and clinical uses of the buccal fat pad" Yousuf, S et al Surg Radiol Anat (2010) 32:427–436

3. "The Endonasal Endoscopic Harvest and Anatomy of the Buccal Fat Pad Flap for Closure of Skull Base Defects" Markey, J et al The Laryngoscope 125: 2247-2252

4. "Bichectomy or Bichatectomy - A Small and Simple Intraoral Surgical Procedure with Great Facial Results" Eber Luis de L S. Adv Dent & Oral Health. 2015; 1(1): 555555. DOI: 10.19080/ADOH.2015.01.555555.

5. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8th Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

Image: By Otto Placik (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons] Click here for the link to the original image

- Details

The term [quadratus] is Latin and means “square”, it is also the root of the Spanish word “cuadrado”.

It is used to several structures in the body that are of course, square, or at least square-like:

• Quadratus lumborum muscle

• Quadratus femoris muscle

• Pronator quadratus muscle

These muscles will be described in separate articles

Sources: 1. “Understanding Anatomical Terms” Mehta, LA, et al. Clin Anat 9:330-336 (1996)