Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 792 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

Galen of Pergamon

(129AD - 200AD

The word sympathetic is the adjectival form of sympathy. This word arises from the Greek [συμπάθεια]and is composed of [syn/sym] meaning “together” and [pathos], a word which has been used to mean “disease”. In reality “pathos” has to do more with the “feeling of self”. Based on this, the word sympathy means “together in feeling”, which is what we use today.

How the term got to be used to denote a component of the so-called autonomic nervous system is part of the history of Medicine and Anatomy.

Galen of Pergamon (129AD-200AD), whose teachings on Medicine and Anatomy lasted as indisputable for almost 1,500 years, postulated that nerves were hollow and allowed for “animal spirits” to travel between organs and allowed the coordinated action of one with the other, in “sympathy” with one another. As the knowledge of the components of the nervous system grew, this concept of “sympathy” stayed, becoming a staple of early physiological theories on the action of the nervous system.

Jacobus Benignus Winslow (1669-1760) named three “sympathetic nerves” one of them was the facial nerve (the small sympathetic), the other the vagus nerve, which he called the “middle sympathetic”, and the last was what was known then as the “intercostalis nerve of Willis” or “large sympathetic", today’s sympathetic chain. Other nerves that worked coordinated with this “sympathetics” were considered to work in parallel with it. It is from this concept that the term “parasympathetic” arises.

Interestingly, the ganglia on the sympathetic chain were for years known as “small brains” and it was postulated that there was a separate multi-brain system coordinating the action of the thoracic and abdominopelvic viscera. The coordination between this “autonomous nervous system” and the rest of the body was made by way of the white and gray rami communicantes.

Today we know that there is only one brain and only one nervous system with an autonomic component which has a “sympathetic” component that is mostly in charge of the “fight or flight” reaction and a “parasympathetic” component that has a “slow down” or “depressor” function. Both work coordinated, so I guess Galen was not "off the mark" after all.

So, we still use the terms “sympathetic” and “parasympathetic”, but the origin of these terms has been blurred by history.

Sources:

1. "Claudius Galenus of Pergamum: Surgeon of Gladiators. Father of Experimental Physiology" Toledo-Pereyra, LH; Journal of Investigative Surgery, 15:299-301, 2002

2. "The Origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, HA 1970 Hafner Publishing Co.

3. "Medical Meanings:A Glossary of Word Origins" Haubrish, WS American College of Physicians Philadelphia, 1997

4. "The History of the Discovery of the Vegetative (Autonomic) Nervous System" Ackerknecht, EH Medical History, 1974 Vol 18.

Original image courtesy of Images from the History of Medicine at nih.gov

Note: The links to Google Translate include an icon that will allow you to hear the pronunciation of the word.

- Details

The medical term [epistaxis] refers to a “nose bleed”.

It is considered to be a Modern Latin term that originates from the Greek word [επίσταξη] (epístaxí). The word is composed of [επί] [epi-] meaning "on", "upon", or "above", and [στάζει] (stázei), meaning "in drops", "dripping".

The term was first used by Hippocrates, but only as [στάζει] , to denote dripping of the nose, and was later changed to [επίσταξη] to denote “dripping upon”. The term itself does not include or denote that the blood loss is from the nose, but its meaning has been implied and accepted for centuries. The plural form for epistaxis is epistaxes.

Skinner (1970) says that the term was first used in English in a letter by Thomas Beddoes (1760-1808) in a letter to Robert W. Darwin (1766-1848) in 1793. Robert Darwin was an English physician, father or Charles Darwin (1809-1882) author of “The Origin of the Species”.

Sources:

1. "The Origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, HA 1970 Hafner Publishing Co.

2. "Medical Meanings - A Glossary of Word Origins" Haubrich, WD. ACP Philadelphia

Note: The links to Google Translate include an icon that will allow you to hear the pronunciation of the word.

- Details

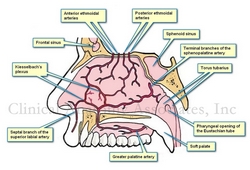

Kiesselbach's plexus is named after Dr. Wilhelm Kiesselbach (1839 – 1902), a German otolaryngologist. It is an area in the anteroinferior aspect of the nasal septum where several arteries from different origins meet and anastomose.

This arterial plexus is also known as the "locus Kiesselbachii, Kiesselbach's triangle, or Little's plexus, or Little's area. This area of the anteroinferior nasal septum has a propensity for epistaxis or nasal bleeding. In fact, close to 90% of nose bleeds (epistaxes) happen in this area.

There is a secondary area where epistaxis may happen, but this is a venous nose bleed. This is Woodruff's plexus, a venous plexus found in the posterior aspect of inferior turbinate on the lateral wall of the nose.

Thanks to Jackie Miranda-Klein for suggesting this post.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Letter from Ephraim McDowell

to Robert Thompson

As some of you may know by now, I am a collector of antique medical books and books that relate to the history of anatomy and medicine.

As important as the books themselves are, there are details beyond the book itself that can take hours of my time doing research. The first one is the bookplates (also known as Ex-Libris). The have been used for centuries by book owners and collectors to identify the books in their collections, a tradition that seems to be falling in disuse. Not me, I have one that you can see here. Some of these can lead to places that you cannot imagine initially. One of these bookplates took me to research a potential resident ghost in a library!

Provenance is also important. Where was it printed? Who owned it? Who was the illustrator? etc. I recently acquired a second copy of the book “EPHRAIM MCDOWELL, FATHER OF OVARIOTOMY AND FOUNDER OF ABDOMINAL SURGERY. With an Appendix on JANE TODD CRAWFORD”. By AUGUST SCHACHNER, M.D. Cloth, 8vo.A p. 33I. Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott CO., I921. Dr. McDowell has also been featured in this blog in the series "A Moment in History".

This second copy is most valuable because of the papers found within the book. There is a series of notes, newspaper clippings, and copies of letters! Here is a detail of what I have found:

The book seems to have belonged to Cecil Stryker, MD.,a physician in Cincinnati, and one of the founders of the American Diabetes Association (ADA). There is a copy of a letter by Dr. Ephraim McDowell to Dr. Robert Thompson (Sr.) dated January 2nd, 1829, a year before Dr. McDowell's death. The letter is shown in the image attached. In this letter Dr. McDowell describes in his own words the ovariotomy he performed on Jane Todd. He also describes other ovariotomies he performed and his opinion on "peritoneal inflammation".

There is a note from Dr. Cecil Striker to "Bob" dated 6/3/73 when he gifted a copy of this book. In the note Dr. Striker explains that he bought several copies of the book and he is sending this copy to him. There is also a copy of Dr. McDowell's prayer (costs 25 cents), and a page of the Kentucky Advocate newspaper published in Danville, KY and dated Sunday April 15, 1973 on the restoration of Dr. Alban Goldsmith home, a surgeon who assisted Dr. McDowell in his first ovariotomy (first in the world, that is).

Last, there is a note dated September 16, 1974 from the wife of Dr. West T. Hill, Chairman of the Dramatic Arts Department at Centre College in Danville, Kentucky. In this handwritten note she mentions the McDowell family reunion that took place on June 15 and 16, 1974 in Danville. With the note comes the program and registration form for the festivities! Dr. West T. Hill was one of the many responsible for the restoration of the MacDowell Home and Museum. Today Danville has the West T. Hill community theatre that honors his name.

All of this in one book, as I always say "You know where you are going to start reading it, but you never know where are you going to end in researching it". This book will be a great addition to my library catalog. Dr. Miranda.

- Details

Rudi Coninx, MD is a physician and Chief a.i. Humanitarian policy and Guidance at the World Health Organization (WHO), based in Geneva. He obtained his MD from the University of KU Leuven Belgium, a Doctorate in Tropical Medicine from the Prins Leopold Instituut voor Tropische Geneeskunde, and an MPH from the John Hopkins University School of Medicine.

His CV shows more than twenty five years of national and international experience in policy and strategy development and analysis, policy dialogue, technical advice and program management support to countries and WHO country offices. Considerable experience in strengthening WHO country offices and in working with partners and networks at the global as well as filed level. Coordinated the WHO Country Focus Policy for more than five years and worked as a member in various strategic planning, decentralization, and global and regional partnership groups, including national and international committees, taskforces. Published several articles on policy analysis, management and health and development in regional and international journals.

He is also an Associate Faculty, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, USA.

He has held a series of positions with the International Committee of the Red Cross, and also within the World Health Organization. His LinkedIn profile can be found here.

Thanks to Dr. Coninx for taking time of his busy schedule and collaborating with "Medical Terminology Daily" with the article "Did Andreas Vesalius really die from scurvy?" which he co-authored with Theo Dirix. We look forward to his future writings in this blog.

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Wilhelm Kiesselbach

Wilhelm Kiesselbach (1839 – 1902) German otolaryngologist born in the city of Hanau. Started his medical studies in 1859 in Göttingen. Marburg, and Tübingen. Because of an accident that affected one of his hands and legs, his doctorate was delayed until 1875.

He specialized in otolaryngology in Vienna, although he also studied and specialized in ophthalmology. He had a number of positions such as assistant professor at the Medical Polyclinic in Erlangen, assistant professor for ophthalmological examinations at the Surgical Clinic in Erlangen, and senior physician for ophthalmology.

He died of an infection he contracted while working with patients at the clinic.

His name is eponymically tied to the locus Kiesselbachii, also known as Kiesselbach’s plexus, an area of the anteroinferior nasal septum known for propensity for epistaxis or nasal bleeding. In fact, close to 90% of nose bleeds happen in this area. in this region, terminal branches of the anterior ethmoid artery, greater palatine artery, sphenopalatine artery and superior labial artery anastomose forming a plexus.