Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 929 guests online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

GoFundMe Campaign for the next stage of the project

A group of researchers and investigators are looking to the incredible possibility of finding the grave of Andreas Vesalius. Initially this led to the 2014 meeting "Vesalius Continuum" in the island of Zakynthos, Greece. At that time Dr. Sylviene Déderix, Pascale Pollier, and Theo Dirix presented the status of the research that led to identification of the location of the church where Vesalius was buried. This was the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie which would have been located in the northern sector of the modern town, around the current junction of Kolokotroni and Kolyva streets.

More on this original stage on the project was published on the following article: In Search of Andreas Vesalius, The Quest for the Lost Grave - The Sequel. Supporters for this research include world-renown scholars such as Prof. Omer Steeno and Dr. Maurits Biersbrouck, which appear in the video

The next stage in this quest is to perform a detailed analysis of the grounds around the church using Electrical Resistive Tomography (ERT) and Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) as well as other non-invasive ground-sensing modalities. This kind of research is not cheap and requires funding.

Pascale and the research team have set a GoFundMe campaign to raise €9,900, roughly US$10,800, and I am asking all of the Vesalius followers and anatomy enthusiasts to contribute as little or as much as you can to make this next stage of the project a reality. You can reach the GoFundMe page here.

The video in this article is by courtesy of Vimeo.com

- Details

This is a series of articles on depression and published as a community service. The information in these articles follow our Privacy and Security Guidelines and cannot be construed as medical guidance. For additional information and counseling, consult with your physician or the appropriate health care professional of your choice. You can also find information on Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) here. For the initial article on this series click here.

The medical term meaning "cause" is [etiology]. As you talk to a physician or research on the causes of depression knowing this term will come in handy. Most likely, the etiology of depression is a combination of genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors.

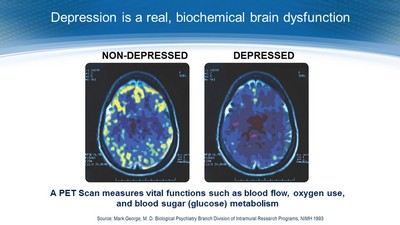

Depressive pathologies are disorders of the brain. Brain-imaging technologies, such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), have shown that the brains of patients who have depression are physically different than those of non-depressed individuals. This is important to understand. A depression patient is not a "mental" or "crazy" person in the fact that there is an underlying physical brain disorder causing the depression. They are not "faking it" and the treatment must look into getting the brain back into a normal physical pattern.

The following images show a Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scan of both a non-depressed and a depressed individuals. In these images the areas of the brain involved in mood, thinking, sleep, appetite, and behavior appear different. These images do not reveal why the depression has occurred, only that a depressed brain is physically different from a non-depressed brain.

Click on the image for a larger view

Some types of depression tend to run in families, indicating a genetic base for the pathology. However, depression can occur in people without family history of depression. Scientists are studying certain genes that may make some people more prone to depression. Some genetics research indicates that risk for depression results from the influence of several genes acting together with environmental or other factors. In addition, trauma, the loss of a loved one, a difficult relationship, long winter seasons, or any stressful situation may trigger a depressive episode. Other depressive episodes may occur with or without an obvious trigger.

Who is at risk?

Major depressive disorder is one of the most common mental disorders in the United States. Each year about 6.7% of U.S adults experience major depressive disorder. Women are 70 % more likely than men to experience depression during their lifetime. Non-Hispanic blacks are 40% less likely than non-Hispanic whites to experience depression during their lifetime. The average age of onset is 32 years old. Additionally, 3.3% of 13 to 18 year olds have experienced a seriously debilitating depressive disorder.

Depression also may occur with other serious medical illnesses such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, HIV/AIDS, diabetes, and Parkinson's disease. People who have depression along with another medical illness tend to have more severe symptoms of both depression and the medical illness, more difficulty adapting to their medical condition, and more medical costs than those who do not have co-existing depression. Treating the depression can also help improve the outcome of treating the co-occurring illness

Source: National Institute of Mental Health

Next article: Types of Depression

- Details

A reminder of one of the joys of summer! The term [sphenopalatine ganglioneuralgia] is a fancy medical term for "brain freeze". which happens when we eat or drink very cold food.

The etymology of the term is complex. [Sphen-] is a term meaning "wedge" and refers to the sphenoid bone. [-palatine-] means "pertaining to the palate" (and to the bones related to the hard palate].

The root term [-gangli-] refer to a ganglion, which is a concentration of neuronal bodies, neurons being the main cells of the nervous system. [-neur-] means "nerve", and the suffix [-algia] means "pain". Simply said, the term [sphenopalatine ganglioneuralgia] means "nerve pain of the sphenopalatine ganglion".

The sphenopalatine ganglion (Meckel's ganglion, nasal ganglion or pterygopalatine ganglion) is a parasympathetic ganglion found in the pterygopalatine fossa. It is largely innervated by the greater petrosal nerve (a branch of the facial nerve); and its neuronal axons innervate the lacrimal glands and nasal mucosa.

Not everybody accepts this theory. Some state that "brain freeze" occurs because of rapid cooling of the blood in the pharynx, causing a drop of temperature of the internal carotid artery, which in turn causes cooling and pain in the meninges related to the base of the cranium.

My thanks to Gina Burg, for bringing this term to my attention. Dr. Miranda

Thanks to Forrest J. Bonjo for the image and additional information. The article was originally stored at pdu.edu, but the server was closed. If you click on the image, this will take you to the article stored at web.archive.org.

- Details

There are many in the world that are fascinated by the life and works of Andreas Vesalius (1514 -1564). This has created a market for “Vesaliana”. These are books, art, medals, and works are related to Vesalius. As an example, an original 1543 Fabrica sells today for 400 thousand dollars! Even the “New Fabrica” by Drs. Garrison and Hast has cuadrupled its value in only two years since its publication!

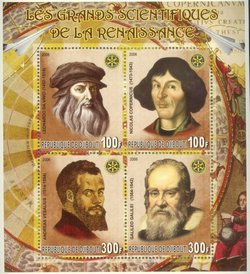

Some of the most coveted items are stamps that celebrate the illustrious anatomist. Probably the most detailed research on the topic was made by Prof. Omer Steeno and Dr. Maurits Biersbrouck, both contributors to this website. Their research is constantly updated and the latest iteration of their work is “Andreas Vesalius in Philately” published in WordPress.com.

In a recent private communication Prof. Steeno regretted that unscrupulous individuals have taken to forge and falsify stamps. A clear case of this is the stamp collection “Les Grands Scientifiques de la Rennaissance” published in November 23, 2006 by the Republic of Djibouti. The stamps (shown in the accompanying image) depict Leonardo da Vinci, Nicolas Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, and Andreas Vesalius. As a Vesaliana collector, who would not want this set of stamps placing Vesalius in such company?

Djibouti is an African country that gained its independence from France in 2007 and is located in the horn of East Africa and the opening of the Red Sea into the Gulf of Aden.

Drs. Steeno and Beisbrocuk contacted the Djibouti postal service and were able to confirm in February, 2016 that indeed these stamps are false and collectors should be aware.

Sources:

1. “Andreas Veslius in Plhilately” Steeno, O; Biesbrouck, M 2016

2. Private communication. Steeno, O. 2016

3. “On the falsification of a Vesalius Stamp wrongfully ascribed to the postal service of Djibouti” Steeno, O; Biesbrouck, M 2016. EMediTheme 2016 Editor: Menzies, S.

- Details

This is a series of articles on depression and published as a community service. The information in these articles follow our Privacy and Security Guidelines and cannot be construed as medical guidance. For additional information and counseling, consult with your physician or the appropriate health care professional of your choice. You can also find information on Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) here. For the initial article on this series click here.

UPDATED: People with depressive pathology do not all experience the same symptoms. The severity, frequency, and duration of symptoms vary depending on the individual and his or her particular illness. Because symptoms are subjective, some patients will not express or hide them, making the diagnosis of depressive disorder difficult.

Following are the description of the symptoms by two different patients:

Patient 1

"It was really hard to get out of bed in the morning. I just wanted to hide under the covers and not talk to anyone. I didn't feel much like eating and I lost a lot of weight. Nothing seemed fun anymore. I was tired all the time, and I wasn't sleeping well at night. But I knew I had to keep going because I've got kids and a job. It just felt so impossible, like nothing was going to change or get better."

Patient 2

"I felt dirty and unwashed. All my surroundings felt dirty and I spent hours cleaning the house with no results. I took long baths and even after them I still felt dirty. My sleep was broken with horrible nightmares with gore and destruction. I felt tired, mostly because I could not sleep. I cried every morning because I felt like a total failure. I felt ugly and no amount of makeup could cover this feeling. I did not want to go out in public at all"

Signs and symptoms of depression may include:

• Persistent sad, anxious, or "empty" feelings

• Feelings of hopelessness or pessimism

• Feelings of guilt, worthlessness, or helplessness

• Irritability, restlessness

• Loss of interest in activities or hobbies once pleasurable, including sex

• Fatigue and decreased energy

• Difficulty concentrating, remembering details, and making decisions

• Insomnia, early-morning wakefulness, or excessive sleeping

• Overeating, or appetite loss

• Thoughts of suicide, suicide attempts

• Aches or pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems that do not ease even with treatment

Next article: Causes of Depression

- Details

This is a series of articles on depression published as a community service. The information in these articles follow our Privacy and Security Guidelines and cannot be construed as medical guidance. For additional information and counseling, consult with your physician or the appropriate health care professional of your choice. You can also find information on TMS here.

UPDATED: Everyone occasionally feels blue or sad. There are also those dreaded "winter blues". But these feelings are usually short-lived and pass within a couple of days, usually with no problems or persistent symptoms. Some people may even say that they are "depressed". Although this is true, that person is not clinically depressed.

When an individual has clinical depression, there are physical changes that happen within the brain which reflect in attitudes, mood, symptoms, and actions.

Clinical depression is a common but serious mental disorder that affects over 20 million people in the United States, many of which will never seek diagnosis or treatment. Patients present with depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, decreased energy, feelings of guilt or low self-worth, abnormal patterns of sleep or appetite, gruesome nightmares, and poor concentration. Moreover, depression may often come with symptoms of anxiety and varying complex presentations of bipolar disorder.

These problems can become chronic or recurrent and lead to substantial impairment in an individual’s ability to take care of his or her everyday responsibilities. At its worst, depression can lead to a patient's attempt on their life. Clinical Depression interferes with daily life and causes pain for both the individual, their families, and loved ones. Patients with depressive disorder often go from one job to another, cannot work, or eventually end in disability, being maintained by their family or loved ones.

Many people afflicted with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) never seek treatment. This is specially true in males, where the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that ”fewer than 25% of male sufferers worldwide will seek treatment because of the social stigma associated with mental disorders including depression.”

Properly and timely treated, even those with the most severe depression, can get better. Medications, psychotherapy, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) are the most common methods to treat depression. As patients move from one medication to the next level medication as well as augmentation medication, the annual cost for medication can be staggering, as well as the common, insidious, and problematic systemic side effects of both the drug therapy and ECT therapy.

The main objective of all treatments for MDD is to attain remission, but in many cases just reducing the symptoms of MDD and reducing the amount and types of medication used is enough to bring the patient back to a productive life and enhance the relationship with their families and loved ones.

Next article: Symptoms of Depression