Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 742 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

Note: The following article was recently published in Dutch by my good friend Theo Dirix. Theo is one of our "Vesaliana" contributors, and he has written or has been part of several of the articles in this website. Theo was kind enough to provide a translation of his publication for this blog. There are footnotes in the original publication and I have added them to the end of this article. Dr. Miranda

Christie’s in New York recently sealed the deal of an exceptional copy of the Fabrica, the masterpiece by Andreas Vesalius. The sound resonated widely: buyers were the alma mater of the doctor, the KULeuven (University of Louvain, Belgium), and the Flemish government.

Earlier, a copy of Vesalius’s 1538 adaptation of a teacher’s manual, with his own notes, had already gone under the hammer. This copy of the second edition of the Fabrica from 1555, also richly annotated by the author, was not allowed to escape.

Vesalius enthusiasts eagerly anticipate seeing this historical wonder with their own eyes, following the promised digitization by the KULeuven and its exhibition in their ‘experience center’.

Non-medical or non-Latinist individuals may also find Vesalius captivating. The allure of such a well-traveled, exceptionally driven, and art-loving man is infectious and timeless. The Inquisition had no control over him, and his free-spirited mind and interactions with those of differing beliefs, such as Protestants or Jews, continues to inspire today.

At the end of the First Book of the Fabrica, there is a list of names for the bones of the skeleton as Vesalius knew them: first as he himself preferred to use them, then in Greek and in the Latin of others, and finally in Hebrew. In a certain way, the latter is also the Arabic translation, so he says, as they are “almost all taken from the Hebrew translation of Avicenna by my good Jewish friend and eminent physician Lazarus de Frigeis (with whom I usually study Avicenna).” 1

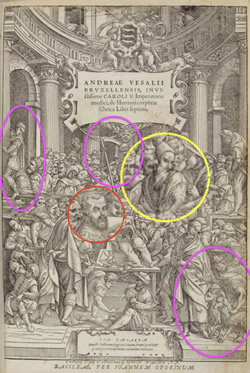

The opening print of the Fabrica may even feature an image of his friend. After all, Vesalius had one of his public dissections illustrated. 2

"A colorful crowd, rows deep, stands, hangs, and drums around the table on which a corpse is being dissected. Three quarters of almost two hundred guests are students, with about fifty doctors and other notables also in attendance."

That is how the German student Baldasar Heseler described in his diary a public dissection in Bologna, conducted by the Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius.

Among the attendees were likely curious individuals who also frequented public executions or animal fights. Dissections were not serene practical lessons like today. Sometimes several dissections followed each other, often chaotic and in a festive atmosphere during the carnival period: today a hanged man, tomorrow a prostitute, in between a dog.

The image Vesalius chose for his first version of the Fabrica in 1543 is more symbolic in nature. Various authors see allegories in the ninety characters, as well as historical and contemporary prominent figures and acquaintances. 3

A striking figure who is central yet isolated is a man with a long beard, red in some colored versions, wearing a truncated conical headdress such as a tarboosh or fez. He turns towards his neighbor who whispers or shouts something to him. Or is he responding to the scene unfolding beneath him with the dismissive gesture of his left hand? With understanding or disgust?

Like other guests, he wears a heavy cloak; dissections were preferably performed during the cold winter months. It may be far-fetched, but don’t those stripes on his cloak remind us of the threads of a Jewish prayer shawl? Is this “his good Jewish friend and leading physician Lazarus de Frigeis”?

In the opening print of the second version from 1555, the stripes or threads are less clear. The sharp gaze is also blurred. And isn’t that beard shorter? Things have indeed changed in twelve years.

For example, the originally naked spectator on the balcony now wears a suit. The dog, bottom right, has a goat or goat next to him: is that perhaps the devil? The pennant of the all-dominating skeleton in the center becomes a scythe in the hands of Death.

Many find the later image less appealing than the original and speculate as to the reasons: Was it created by a different and perhaps less talented artist? Was the initial woodcut set aside because it had already been extensively used? Do the alterations suggest censorship or self-censorship, perhaps with an eye towards the advancing Inquisition?

Vesalius also made numerous changes to the text in the second edition. It remains a mystery how he communicated these changes to his Basel printer, Oporinus. This curiosity extends to his annotations and the third edition he had in mind. For instance, in the second edition, he omitted all references to his friends, retaining only the mention of Lazarus de Frigeis. However, the descriptors ‘Jewish’ and ‘leading physician’ were removed. Lazarus is still described as “his good friend.” Why did the reference to Judaism have to vanish?

One explanation posits that the descriptor ‘Jew’ had become redundant. Following the perspective of a researcher who identifies Lazarus de Frigeis as Lazzaro Freschi, the son of Rabbi Raffaele Fritschke, it is thought that Lazarus converted to Christianity in 1549, assuming the name Giovanni Battista Freschi Olivi. 4

Another explanation suggests that it may have been safer at the time to avoid allusions to Jewish beliefs or conversions. According to the same source, Lazzaro Freschi and his mother moved, or were compelled to move, to the Venice ghetto in 1547.

The word ‘getto’ is Italy’s ‘contribution’ to anti-Semitism, akin to later terms such as ‘pogrom’ from Russian, ‘Endlösung’ from German, and the slogan in English today commonly heard on European streets: “From the River to the Sea”.

Vesalius, however, continued to refer to Lazarus de Frigeis as his good friend. Not only was the anatomist well-traveled, passionate about his work, and an admirer of art, he was also loyal, open-minded, and, above all, courageous.

Theo Dirix

With gratitude to Omer Steeno, Maurits Biesbrouck, and Theodoor Goddeeris

Footnotes:

1. based upon: Maurits Biesbrouck. Nederlandse vertaling van het eerste boek van Andreas Vesalius’ Fabrica 1543, handelend over het Menselijk Skelet. P. 394.

2. with differences in the frontispieces of the Fabrica’s of 1543 and 1555: https://exhibitions.lib.cam.ac.uk/vesalius/

artifacts/coloured-frontispiece-1543/, and https://library.missouri.edu/specialcollections/exhibits/show/vesalius500/fabrica/a-tale-of-two-title-pages

3. for example: C.D. O’Malley. Andreas Vesalius of Brussels 1514-1564, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los

Angeles, 1964, p. 140.

4. Toaff, Ariel. Pasque di sangue, Ebrei d’Europa e omicidi rituali, Societa editrice il Mulino, Bologna, 2007, p. 197 - 198

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Everybody has the hope of someday finding a treasure, and we look for it in garage sales, antique shops, anywhere and everywhere. As a book collector, I live for the day when I find a precious book that has been overlooked and that I can add to my collection. This is the story of such a find by a book collector who not only found the treasure, but sold it!!.

No one knows exactly how many copies were printed of Andrea Vesalius' magnificent book “De Humani Corporis Fabrica, Libri Septem”. It is estimated that each run of the first (1543) and second (1555) editions were between 600 -1000 copies, maybe less. The censuses on the surviving copies of this book published by S. Joffe, MD and V. Buchanan in 2015 tell us that less than 60 copies of each of these books exist in the USA, and the total worldwide number is unknown.

Most of the books available today are in rare book repositories at university libraries, and only a few are available to private book collectors.

The price for a good copy today is close to half a million US dollars (or more). Although some copies can be found for less, they are probably not original, and could be one of the many plagiarized copies of this wonderful book.

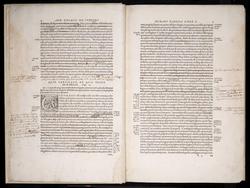

In 2007, Vancouver pathologist and book collector Dr. Gerard Vogrincic bought a Fabrica at auction in Germany. This was not the best copy of the Fabrica. The index (an important part of the book, as it was the first anatomy book to ever have one) was missing, but most important, the book text was heavily underlined and annotated; some paragraphs were crossed out with ink, and over one thousand annotations were found on the sides of the pages, as well as in the images, a critical part of this book and the reason for its fame. As a result, the price at the auction was not too high, as it sold for US$14,256.

A careful revision of the handwritten notes led Dr. Vogrincic to believe that the notes may have been written by Vesalius himself, but he had no idea of how to confirm it and he could not read Latin, the language of the annotations. There are only a few examples of Vesalius’ handwriting, as Vesalius burned many of his notes and letters, and only some survived. Dr. Vogrincic obtained a facsimile of one of Vesalius’ letters and was surprised that indeed the writings matched!

Dr. Vogrincic contacted Dr. Vivian Nutton, Emeritus Professor at the UCL Center for the History of Medicine in London. Dr. Nutton, a Latin scholar and Vesalius expert confirmed that this was a book that not only belonged to Vesalius, but that the handwriting, and the style of the Latin annotations was Vesalius'!. The book includes corrections to the style, grammar, anatomy, images, and also instructions for a third edition that was never published.

For a time, the book was on a "permanent" loan at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library in University of Toronto, Canada, part of a 2015 exhibit, and was an important addition to the translation and annotations for the “New Fabrica” authored by Drs. M. Hast and D. Garrison. The New Fabrica is now out of print.

In 2022, toward the end of the COVID pandemic, the University of Cincinnati and the Henry R. Winkler Center for the History of the Health Professions, held an online and in-person exhibit and series of lectures entitled "The Illustrated Human: The Impact of Andreas Vesalius". One of the lectures was on the Annotated Fabrica. You can watch the whole lecture and interview with Dr. Gerard Vogrincic and Dr. Vivian Nutton here. Here is the link for "The Illustrated Human online exhibit".

Following is a YouTube video by Philip Oldfield, curator of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library in University of Toronto, Canada, talking about this book

This book was sold on February 2nd, 2024 on auction at Christie's New York, for the incredible sum of 2.23 million US dollars. his is one of the top 10 highest amounts of money ever paid for a book. The link posted here will take you to the auction page and 17 images and a video by Christie's curator Rhiannon Kohl.

It is only fitting that the buyer of the Annotated Fabrica was non other than the University of Leuven, in Belgium, which is the first University that Vesalius attended. In fact, one of the most treasured documents of this University (until now) was the book where Vesalius signed when he matriculated at the University of Louvain (Louven) on February 25, 1530, at 15 years of age. He signed this registry as "Andreas Vesalius Bruxellensis". I had the opportunity of seeing this document personally in 2003.

My personal thanks to my good friend Ron Blumenfeld, MD, world traveler, collector, and author of the book "The King's Anatomist, The Journey of Andreas Vesalius" for bringing this auction to my attention. He also posted an article about this auction titled "Five Centuries Later, Andreas Vesalius Flashes His Star Power".

Another article on this topic was published by New Atlas titled ""Bookfind of the century" sells for $2.23 million"

Sources:

1. “The annotated Vesalius” Duffin, J; Duffin, J. CMAJ (2014) 186:11, 856-857

2. “A Clever Collector Makes an Astonishing Discovery” Vogrincic, Click here for the article

3. “Vesalius Revised. His Annotations to the 1555 Fabrica” Nutton, V. Med. Hist. (2012), 56(4), 415–443 Click here for the article

4. “Updated Census in USA of First Edition of Andreas Vesalius’ ‘De Humani Corporis Fabrica’ of 1543” Joffe, SN; Buchanan V. International Archives of Medicine; 2015: 8:1

5. “An Updated Census of the Edition of 1555 of Andreas Vesalius’ De Humani Corporis Fabrica in the United States of America” International Archives of Medicine; 2015: 8:1

6. “Vesalius’ notes for unpublished edition of De Fabrica” Click here for the website

7. "A Spectacular New Arrival" Oldfield, P; The Halcyon, Issue 49, June 2012 Click here for the article

Note: This article was originally published in 2017, and has been updated several times, in 2019, 2022, and 2023. This is the last version (for now).

- Details

Lecturing on Medical Terminology, Clinical Anatomy, Medical History, Sales, and basics of Surgery for so many years, I have developed an appreciation for proper language in medical communication. I can understand that sometimes medical professionals use vernacular language to convey information to patients, but I have seen and heard many mistakes. The following lists some medical terms that are used incorrectly. I call them my "pet peeves" in medical communication. Dr. Miranda.

1. In the heart, heart valves, and valve ring valvuloplasty arena, everybody talks about the “anulus” of the different valves, but most everybody misspells this term. The word anulus originates from the Latin term “anulus” meaning “ring”. The proper way of writing it is ANULUS not ANNULUS, with a double "n"

2. The word “process” is English. therefore its plural form should be pronounced as “processes” not with a Latinized inflection as “processiiis”.

3. The inflammation of a tendon is “tendonitis”, not “tendinitis”. The root term for tendon is "tendon" (no changes). The term originates separately from the Latin "tendere", to stretch, and originally from the Greek [τένω} meaning " to stretch" or "sinew". The term was wrongly changed in medieval times to "tendin-" and this mistake has stuck through time.

Olive Tapenade (Serious Eats)

4. When there is an excess amount of fluid in the pericardium, that is known as a pericardial effusion. Left untreated, the pericardial effusion can lead to a drastic reduction in cardiac function. This is called a cardiac "tamponade”, not a “tamponaade” (with a French accent) and please don’t call it a “tapenade” (I have heard it), a delicious dish consisting of puréed or finely chopped olives, capers, anchovies and olive oil!

5. The singular form for “criteria” is “criterium”. The following is wrong: “only one criteria was used to make the decision”. The proper sentence should be "only one criterium was used to make the decision".

6. When using a scope to examine the fundus of the uterus, the procedure is a funduscopic procedure, not fundoscopic! It is more euphonic I agree, but not correct!

7. In spinal anatomy, the term “a facet joint” is most commonly used, but the term should be pronounced with the accent on the first syllable as in “fácet”! And just to be a bit more correct, the proper term for a so-called “facet joint” is “zygapophyseal joint”. The term facet is also used to denote each small surface of a diamond.

8. In colon pathology a “diverticulum” is an outpouching of the colon wall. The plural form for “diverticulum” is diverticula. The terms diverticulae or diverticuli are not correct

9. The terms centigrade and centimeter are derivate from the Latin word “centus”, meaning “one hundred”, as in "centurion", a Roman Army commander of one hundred soldiers. Therefore, the French-like pronunciation of centimeter and centigrade with a nasal initial "a", although cool, is not correct!

10. Lately, there is a trend within cardiothoracic surgeons to use the terms "thoratomy", "thoracentesis", "thorascope", and "thorascopy". This is incorrect. The root term for thorax (or chest) is [thorac-], which arises from the Greek [θώρακα] (thóraka) meaning "chest". By definition, root terms are not to be shortened. So, the proper terms to be used are "thoracotomy", "thoracocentesis", "thoracoscope", and "thoracoscopy"

11. Finally, my top pet peeve: The words “anatomy” and “dissection” are actually synonymous. Anatomy has a Greek origin. Ana means “apart” and “otomy” is the “process of cutting”: “to cut apart” Dissection has a Latin origin and means exactly the same! In fact, for many years the term “to anatomize” was used instead of “to dissect”!

Where is the problem? In the pronunciation! “dissection” should rhyme with “dissent”, "fissure", and "dissolve". For a complete article on this topic, click here.

Sources:

1. “"The Doctor’s Dyslexicon: 101 pitfalls in medical language" John H. Dirckx The American Journal of Dermatopathology. 27(1):86-88, FEBRUARY 2005 DOI: 10.1097/01.dad.0000148282.96494.0f PMID: 15677983

2. " Stedman's Concise Medical Dictionary for the Health Professions" John H. Dirckx, Editor

3. "The Origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, HA 1970 Hafner Publishing Co.

4. "Lexicon of Orthopædic Terminology" M. Diab. 1999. Amsterdam Hardwood Academic Publishers.

Thanks to Serious Eats for their delicious tapenade recipe, as well as their permission to use their tapenade image.

Note: Google Translate includes a speaker icon. Clicking on it will allow you to hear the pronunciation of the word.

- Details

We started the Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. website in early 1998. Then the website was written directly in html code and was not easy to maintain, but we did what we could for our friends and customers.

Over the years, as our company grew, we changed our hosting servers to GoDaddy, and our base software to Joomla!, an open-source Content Management System that we believe is the best available, even today. Since we made that decision, we have updated the Joomla! CMS at least twice and we are right now in the process of upgrading the software so this website can be easily read in phones, tablets, and computers. To do this we have an incredible support from Xristoforos Mavros and his company.

In early 2012, fourteen years after we started the www.clinicalanatomy.com website, we decided to start a blog on medical terminology and write on anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their origin, meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Simply stated, we would write on topics that we liked. We decided to call this blog "Medical Terminology Daily", hoping that we would have the time to publish an article every day... oh, how wrong we were on our estimate! Now we are very happy if we have the time to publish weekly!, but we try.

The first article we wrote for this blog was on the term "Bariatric" was October 31st 2012. Since then, over one thousand articles have been published by myself and contributors from all over the world.

Starting 2024, we are revising and updating every single article to review for accuracy, make sure that all links are active (some are 12 years old) and update the images and photographs as needed. This will take time, and it will be a long process, but we think it is worth it.

I hope you enjoy reading this blog as much as we have enjoyed writing it. Dr. Miranda

- Details

- Hits: 7521

This is the first article ever published in this blog, The original date was October 31st 2012. Since then, over one thousand articles have been published.

The term "bariatric" is a compound word with two Greek roots: [βάρος] (város), meaning "weight" or "pressure", and [γιατρός](giatrós) meaning "doctor, physician, or healer". The adjectival suffix [-ic] means "pertaining to". The term bariatric means "pertaining to weight-related medicine".

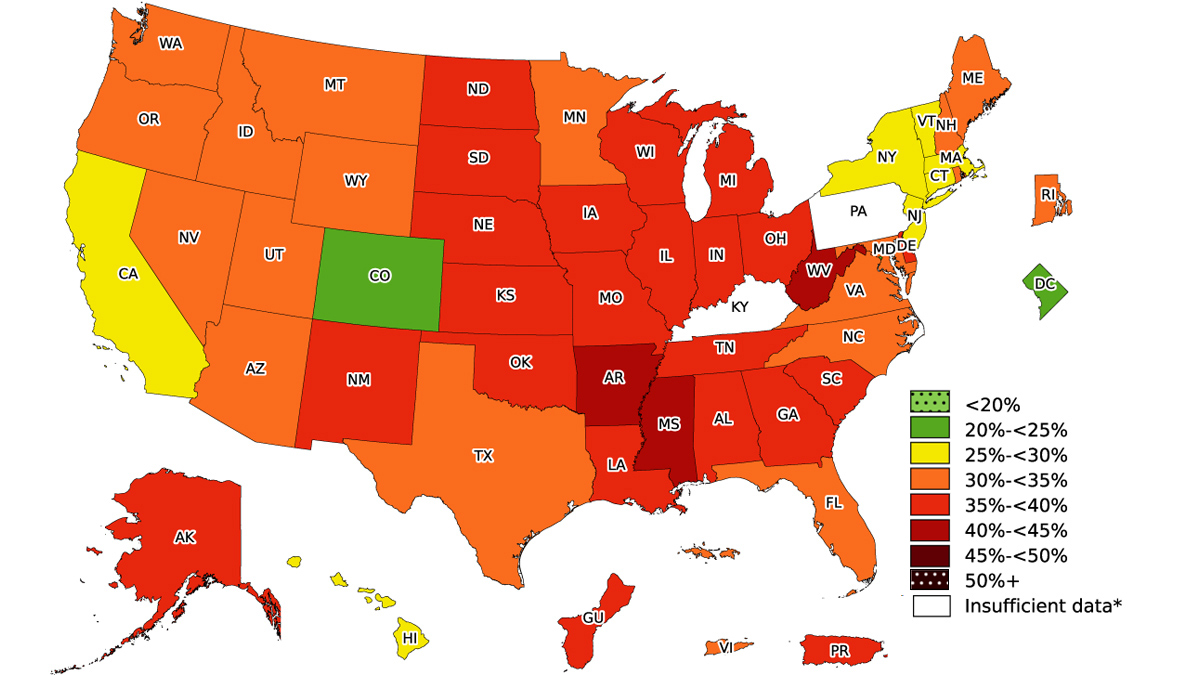

Bariatric surgery is on the rise. In the USA, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) has accumulated data on obesity since 1985, and has a dedicated area in their website on the topic. The most common bariatric surgery as of 2023-24 is the sleeve gastrectomy, where preservation of the stomach magenstrasse and the incisura angularis is extremely important.

The following animated image is based on the CDC information on obesity trends page and the increase in obesity between the years 1985 until 2010. If you click on this image you will download a PowerPoint presentation with these maps

After 2010 the CDC changed the way they collect and publish yearly trends on Adult Obesity Prevalence, adding information on education, age, race, and ethnicity. The following image is this compound map for 2023. For additional information on obesity by the CDC click here.

After 2010 the CDC changed the way they collect and publish yearly trends on Adult Obesity Prevalence, adding information on education, age, race, and ethnicity. The following image is this compound map for 2023. For additional information on obesity by the CDC click here.

The CDC has an Adult Body Mass Index (BMI) Calculator you can use here. If needed, the CDC also has a BMI Calculator for Children and Teens between the ages of 2 to 19 years of age.

The CDC has an Adult Body Mass Index (BMI) Calculator you can use here. If needed, the CDC also has a BMI Calculator for Children and Teens between the ages of 2 to 19 years of age.

Note: Google Translate includes an icon that will allow you to hear the pronunciation of the word

"Gastrointestinal Clinical Anatomy" and "Bariatric Surgery" are among the many educational topics offered by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. Click here to see additional educational materials and lecture topics specifically designed for medical industry professionals.

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Jean-Annet Bogros (1786 - 1825) French physician, surgeon and anatomist. He was born in Bogros, a village in the mountains d’Auvergne, France.His family wanted him to become a priest, but his inclination towards medicine took him to an apprenticeship in the Hôtel-Dieu de Clermont, a hospital under the tutelage of Drs. Fleury, Lavort, and Bertrand. He continued his studies in Paris where he excelled at anatomy. He soon became an intern in Paris Hospitals, and in 1817 he became an assistant at the Faculty of Medicine. He was praised for his anatomical and surgical skills.

In August 29, 1823 he submitted his thesis for his Doctorate in Medicine “Essai Sur L’Anatomie Chirurgicale de la Region Iliaque: Et Description D’un Nouveau Procédure Pour Faire La Ligature Arteres Epigastrique Et Iliaque Externe”. His thesis challenged and improved the technique of ligation of the epigastric and iliac vessels proposed by Abernathy and Astley Cooper. His teaching rivaled the Astley Cooper technique, with an emphasis on hemostasis that was well recognized at the time.

Today his name is eponymically tied to the subinguinal space of Bogros, a triangular area posterior to the superior pubic ramus, lateral to the space of Retzius. This area is bound anteriorly by the deep preperitoneal fascia, and posteriorly by the peritoneum. The medial boundary of this space is either the lateral wall of the urinary bladder, or a sagittal plane passing at the origin of the inferior (deep) epigastric vessels. The superior boundary is the inguinal ligament, while the inferior and lateral boundaries are not described.

Bogros died in 1825 when he was 39 years of age. His cause of death in unknown, but many postulate tuberculosis.

Unfortunately, he was a good and simple man and was described as being meek and soft-spoken. Because of this, he only left one posthumous publication (1827) “Mémoire sur la Structure des Nerfs” where he explains a novel system to inject and identify nerves. This publication, in French, can be read and downloaded here.

Some biographical articles wrongly show his name as Jean-Antoine Bogros, others change the name to Annet Jean Bogros. Both are not correct. In our research we could not find a portrait of Bogros, so we used the cover or his posthumous memoir on the structure of the nerves.

Sources:

1. “Totally Extraperitoneal Herniorrhaphy (TEP): Lessons Learned from Anatomical Observations” Xue-Lu Zhou; Jian-Hua Luo; Hai Huang, et al. Minimally Invasive Surgery 2021(1):5524986

2. "Crucial steps in the evolution of the preperitoneal approaches to the groin: An historical review" R.C. Read Hernia 2010. 15(1):1-5

3. "Retzius and Bogros Spaces: A Prospective Laparoscopic Study and Current Perspectives" Ansari, MM Annals of International Medical and Dental Research, 2017 Vol (3), Issue (5) 25-31

4. " The Preperitoneal Space in Hernia Repair" Lorenz, A et al. Front Surg (2022) Visceral Surgery Vol 9

5. "Essai Sur L’Anatomie Chirurgicale de la Region Iliaque:: Et Description D’un Nouveau Procede: Pour Faire La Ligature Arteres Epigastrique Et Iliaque Externe” J.A. Bogros Imprimerie de E. Duverger. 1827 Paris