Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 3374 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

The term “Bachmann’s bundle” refers to an eponymic structure associated with Jean George Bachmann (1877-1959) a French physician and physiologist. The proper anatomical term for this structure is “interatrial bundle” (Lat. fasciculus interatrialis).

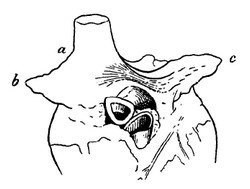

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. He measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of this distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction. The image, from his original publication, shows a dog’s heart with Bachmann’s bundle.

Bachmann’s bundle is a broad, flat band of atrial myocardium that crosses the superior aspect of the interatrial sulcus. It extends from the right atrium close to the junction of the right atrial appendage and the superior vena cava, and courses leftward across the interatrial groove to insert into the base of the left atrial appendage and the anterosuperior left atrial wall. The bundle is well-delineated and in most cases, a fine fatty layer is interposed between the underlying myocardium and the bundle.

This bundle contains predominantly longitudinally oriented myocardial fibers, aiding in fast passage of the electrical depolarization from the right atrium to the left atrium. This explains why, under normal conditions, the left atrium contracts only milliseconds after the right atrium. Bachmann's bundle is one of the components of the cardiac conduction system, and forms part of the specialized bundles of myocardial tissue that take the electrical impulses from the sinoatrial node to the atrioventricular node and the left atrium,

When Bachmann’s bundle is intact, left atrial activation is almost simultaneous with the right atrium. If it is damaged, it can cause varying degrees of interatrial block (IAB), and electrical conduction must proceed through other less effective pathways, resulting in atrial dyssynchrony and altered cardiac rhythm. Advanced IAB is strongly associated with atrial fibrillation, left atrial mechanical dysfunction, and increased risk of stroke even in sinus rhythm.

IAB can be caused by fibrosis, fatty infiltration, atrial dilation, aging, ischemia, and iatrogenic damage in prior cardiac surgery or ablation. All these preferentially affect the anterosuperior interatrial region, explaining the bundle’s vulnerability.

There are anatomical variations of Bachmann's bundle. In some cases, the bundle is separated from the atrial wall by epicardial fat, and in some cases it hugs the surface of the atria. In this last instance the bundle is more susceptible to damage by internal ablation in the left atrial wall. The location of the bundle can also vary.

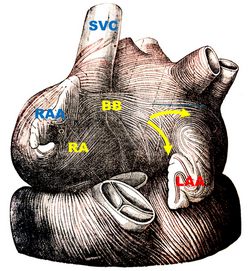

Bachmann’s bundle shows some bifurcations, helping to distribute the depolarization to the left atrium. The image, from Testut & Latarjet (1931), shows one of these bifurcations (yellow arrows). The bundle splits around the base of the left atrial appendage (LAA).

Historically, all pacemakers terminal wires have been implanted in the right atrium. but the potential dysfunction of Bachmann's bundle would require biatrial pacing, which is not used today.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. Antonio Bayés de Luna, Albert Massó-van Roessel, Luis Alberto Escobar Robledo, The Diagnosis and Clinical Implications of Interatrial Block, European Cardiology Review 2015;10(1):54–9

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8th Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

8. 4. Rigamonti F, Shah DC. "Bachmann Bundle Block Occurring During Radiofrequency Ablation at the Inter-Atrial Septum" J Clin Med. 2012;15(9):263.

9. Zhang Y, Wu F, Gao Y, Wu N, Yang G, Li M, Zhou L, Xu D, Chen M. "Bachmann bundle impairment following linear ablation of left anterior wall: impact on left atrial function". Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022 Jan;38(1):41-50

10. Platonov, PG; Mitrofanova, L, et al.Substrates for intra-atrial and interatrial conduction in the atrial septum: Anatomical study on 84 human hearts Heart Rhythm,(2008)5:8,1189-1195.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959) was a French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Sir Arthur Keith and Martin W. Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

Homeostasis is the coordinated set of physiological mechanisms that preserve a stable internal bodily environment (through feedback-controlled regulatory processes) despite fluctuations in the external environment. The concept applies to many dynamic regulations of physiological variables such as body temperature, pH, electrolyte balance, osmolarity, blood glucose, etc.

Claude Bernard (1813–1878) introduced the concept of a “milieu intérieur” the “internal environment” in 1865 where he stated “La fixité du milieu intérieur est la condition de la vie libre et indépendante.” (The constancy of the internal environment is the condition for a free and independent life). Walter B. Cannon (1871–1945) formally coined the term homeostasis in 1929. In his reasoning to name these processes under one name he used the Greek term "ομοιόσταση" [omeóstasí) meaning "constant & stable" or "similar & standing still" referring to a constant (internal) environment.

Disruption of homeostatic processes can contribute to disease states such as diabetes mellitus (failure of glucose homeostasis), heart failure (impaired circulatory stability), heat stroke and/or hypothermia (thermoregulatory failure), hyponatremia or hypernatremia (electrolyte imbalance), etc.

For additional information here is an article from the National Library of Medicine.

Sources:

1. Claude Bernard, "Introduction à l’étude de la médecine expérimentale" (1865).

2. “Organization for physiological homeostasis” Cannon W. B.; Physiol Rev. 1929; 9:399–431.

3. "Textbook of Medical Physiology"; Guyton, Arthur C and Hall, John E ISBN: 0721659446 USA: W.B. Saunders, 1996.

4. “Homeostasis and Body Fluid Regulation: An End Note”. De Luca LA Jr, David RB, Menani JV. Neurobiology of Body Fluid Homeostasis: Transduction and Integration. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2014. Chapter 15

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

The ganglionated plexi are an important part of the rhythm control system of the heart. One of the problems with the concept of the ganglionated plexuses (also known as ganglionated plexi or GPs) is that these structures are rarely mentioned in medical education and are known only to specialists. People looking for information on this topic rarely find a detailed explanation. This article’s objective is to explain these structures and their function, as well as include some historical vignettes. We will start with a review of the structure and organization of the human nervous system.

The nervous system is a complex network responsible for coordinating bodily functions and maintaining homeostasis, that is, to maintain a constant internal environment despite a variable external environment. It operates as the body’s control center, enabling interaction between different parts of the body and facilitating interactions with the environment, both external and internal. It is composed of two main types of cells: neurons and neuroglia, also known as glial cells. Neurons are responsible for transmitting information through electrical and chemical signals. Glial cells support and protect neurons, also helping in their nutrition.

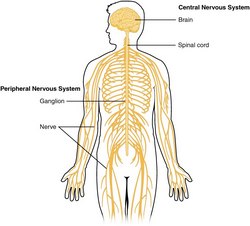

The nervous system is divided into a central nervous system (CNS) and a peripheral nervous system (PNS). The CNS is that portion (brain and spinal cord) contained within the craniospinal cavity and the PNS is composed of neurons and nerves outside this cavity.

It must be noted that these divisions of the nervous system are didactic, that is, they have been created to teach and understand its organization. The fact is that humans have only one nervous system.

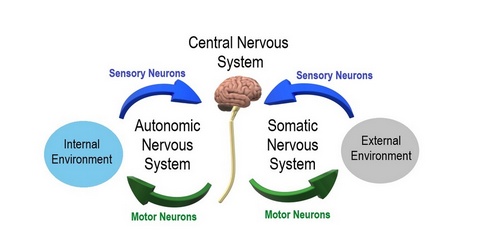

Another division of the nervous system is that of a somatic component and an autonomic component. The somatic component controls voluntary movements and conveys sensory information to the CNS. The autonomic nervous system (ANS) manages involuntary functions such as heartbeat, digestion, urination, etc. For this article we will focus on the ANS.

The ANS is further divided into a sympathetic division, which prepares the body for stress or emergencies (fight or flight response); and a parasympathetic division, which conserves energy, slows down the body and restores the body to a state of calmness (rest and relaxation). Within the ANS we will find motor (efferent) and sensory (afferent) neurons.

Within the PNS and as part of the ANS there are accumulations of neuronal bodies within or close to the internal organs of the body. Each one of these is called a ganglion (Pl. ganglia). The most recognized ganglia are those that compose the sympathetic chain and those related to the origin of most of the branches of the abdominal aorta (Superior mesenteric, celiac, renal, inferior mesenteric, etc.)

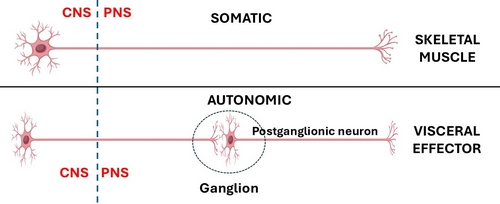

In the case of the CNS somatic (bodily, voluntary) motor organization, is composed of one neuron that is usually located in the frontal lobe motor cortex of the brain in the area known as the precentral gyrus. The distal motor effector of these neurons are distributed to striated (voluntary) muscles throughout the body.

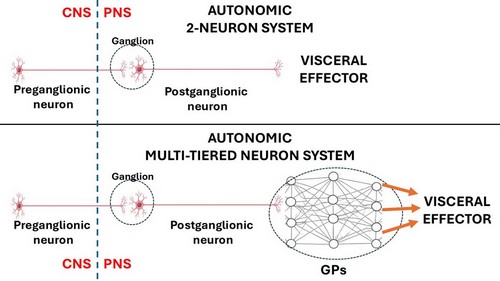

The ANS has been classically described as a 2- neuron system. The body of the first one is found in the CNS and is called the preganglionic neuron, the body of the second one is found in a PNS ganglion and is called the postganglionic neuron, which connects to an autonomic effector (smooth muscle or glands). John Newport Langley (1852 – 1925) a British physiologist coined the terms “preganglionic” and “postganglionic”.

This classic 2-neuron description works for glands and some organs, but it does not consider organs that have rhythmic activity, such as the digestive system and its peristalsis, the heart, ureters, etc.

AI generated image of a neural network

The rhythmicity of these organs is so complex that it requires additional neurons within the muscle layers of each organ. These neurons are found in small intramural ganglia which interconnect with other ganglia by way of nerve fibers forming a complex meshwork (Lat: Plexus). These are the ganglionated plexi (GPs) and their function is to reduce the workload of the CNS by working mostly on their own with oversight of the CNS. These GPs have multiple interconnections forming a neural network, quite similar (on a smaller scale) to the organization of the brain.

Thus, the ANS should be considered as a 2- neuron system in cases such as glands and some organs but, in the case of rhythmic organs there will be ganglionated plexi between the postganglionic neuron and the effector, making it a multiple-tiered system depending on the number of neurons that are interconnected within the GPs.

The two most well-known ganglionated plexi are those found in the muscular and submucosal layers of the small intestine. These plexuses are also found in all the digestive system organs but are more easily studied in the small intestine. They are the plexus of Meissner (submucosal) and the plexus of Auerbach (myenteric). Together they control peristalsis, regulate local secretion and absorption, and modulate blood flow. These nerve plexuses were first described by Leopold Auerbach (1828 -1897) in 1857 and Georg Meissner (1829 – 1905) in 1864.

Because of the importance of these GPs and their activity, they have been called the “enteric nervous system” or the “little brain of the gut” by scientists and journalists. In my opinion, this moniker isolates these GPs from their function as part of the whole of the nervous system.

Another organ that has the same two-layered GPs is the ureter, as described by Pieretti (2018). Neurons (GPs) have been found in the walls of the urethra.

There are organs that have both voluntary and involuntary innervation, such as the urethra, urinary bladder, parts of the anal sphincters, etc. An interesting example of this is the respiratory diaphragm. Most of the day, we are not aware of it working (involuntary – ANS dependent), but if you want to, you can take a deep breath at will (voluntary – somatic dependent)

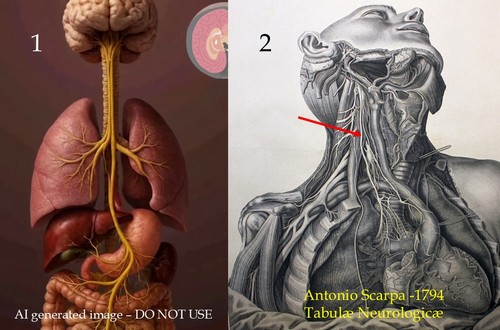

GPs have been described in the heart, which is a quintessential rhythmic organ. Our life depends on its rhythmicity which helps pump blood through the body. Even before the GPs were discovered, the innervation of the heart was described in detail by Antonio Scarpa (1752 – 1832) in his book “Tabulæ Neurologicæ” published in 1794.

The first to describe GPs in the heart was Robert Remak (1815 – 1865) in 1838, they were known as ”Remak’s ganglia”. Later studies were carried out by Woolard (1926), Singh (1996), Pauza (2000), and others. In these research papers great images of the neuron component of these GPs were published.

Before continuing with the topic of the GPs it is necessary to divert slightly to discuss the conduction system of the heart. The conduction system of heart has been described as a group of nodes and fibers that carry electrical impulses within the heart. (sinoatrial node, interatrial and atrioventricular bundles, atrioventricular node, bundle branches, Purkinje fibers). What is not commonly known is that this system is not formed by neurons and nerves, but by specialized cardiomyocytes (heart muscle cells). Each one of these specialized cells has an automaticity that allows them to beat at a specific number of beats per minute (bpm). The further distally within the conduction system the slower the bpm of each of these muscle cells.

So, if each muscle cell has a predetermined bpm count, how does the heart rhythm increase or decrease when needed? The answer lies in complex reflexes mediated by the GPs and in the interaction of the ANS with the GPs of the heart.

The GPs and their interconnections form the intrinsic cardiac nervous system (ICNS), which has several important functions:

Heart Rate Regulation: The GPs modulate the activity of the sinoatrial (SA) node, which is responsible for initiating the heartbeat.

Conduction Modulation: The GPs also modulate the conduction pathways in the heart, particularly the atrioventricular (AV) node and Purkinje fibers, ensuring coordinated contractions of the heart muscle.

Cardioprotection: The GPs help protect the heart by altering cardiac output in response to exercise, stress, ischemia, etc., maintaining heart function and helping homeostasis under challenging conditions.

Coordinate Local Reflexes: The GPs integrate sensory information from the heart and coordinate local reflexes, allowing for rapid adjustments to changes in the heart's environment.

These functions highlight the importance of ganglionated plexuses in maintaining heart health and responding to physiological demands. Dysfunction in these plexuses can lead to various cardiac issues, including arrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation (AFib), and heart failure.

J. Andrew Armour

Cardiac GPs are found in the cardiac wall, although most of them are found intramural and superficial (epicardially) (Tan, 2006), and also embedded in epicardial fat, in the areas devoid of pericardium (formed by the pericardial reflections) around the pulmonary veins, superior vena cava and around the ligament of Marshall. Although GPs are found in the atria and ventricles, there are 5 times more atrial than ventricular GPs (Armour, 1997).

In the study of the GPs, J. Andrew Armour MD, PhD, has been a foundational figure in neurocardiology, and his work has shaped our modern understanding of the intrinsic cardiac nervous system (ICNS), and the GPs. He proposed that the ICNS is not just a passive relay for ANS signals, but a complex integrative network of efferent (motor) neurons, afferent (sensory) neurons, and local circuit neurons that form the GPs. Through his work, Armour argued that the heart’s neuronal network is sufficiently rich to process information, participate in local reflexes, and modulate cardiac function independent of central nervous system input. This can be proven by the heart working normally in heart transplants, completely separated from the recipient's nervous system.

In conclusion, there are two points to consider:

1. The 2-neuron organization of the ANS must be expanded to consider all organs that have rhythmicity and have GPs forming an intramural neural network, following this schema.

2. Our understanding of the rhythmicity of the heart has been one-sided, focusing only on the cardiomyocyte-based conduction system of the heart. This leads to surgical and minimally invasive treatments that do not consider the ICNS and GPs, as well as the location of most of the GPs on the external layers of the heart. A unified approach to these structures will certainly help those patients with cardiac arrhythmias and their surgical treatment.

Sources:

1. Stavrakis S, Po SS. “Ganglionated Plexi Ablation: Physiology and Clinical Concepts.” Heart Rhythm 2017. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 6(4):186–190

2. “The Intrinsic Cardiac Nervous System and Its Role in Cardiac Function” Fedele L, et al. 2020. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 7(4):54.

3. "A brain within the heart: A review on the intracardiac nervous system" Campos, I.D.; Pinto, V.J Mol and Cell Cardiol. 2018 119:1-9

4. "Anatomical Distribution of Ectopy-Triggering Plexuses in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation" Kim, MY et al Circulation" Arrythmia and Electrophysiol 2020. 13:9

5. “Morphology, Distribution, and Variability of the Epicardiac Neural Ganglionated Subplexuses in the Human Heart” Pauza, D., Skripka, V et al The Anatomical Record 259:353–382 (2000)

6. “Gross and Microscopic Anatomy of the Human Intrinsic Cardiac Nervous System” Armour JA et al, (1997) The Anatomical Record 247:289-298

7. “The Junction Between the Left Atrium and the Pulmonary Veins, An Anatomic Study of Human Hearts” Nathan, H; Eliakim, M. Circulation (1966) 34: 412-422

8. “Autonomic innervation and segmental muscular disconnections at the human pulmonary vein-atrial junction: implications for catheter ablation of atrial-pulmonary vein junction” Tan AY, Li H, Wachsmann-Hogiu S, Chen LS, et al J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:132–143

9. “Topography of cardiac ganglia in the adult human heart” Singh S, Johnson PI, Lee RE, Orfei E, Lonchyna VA, Sullivan HJ, et al. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996; 112:943-53

10. Woollard, H. H. “The Innervation of the Heart.” Journal of anatomy (1926) 60 Pt 4: 345-73. 4

11 “Tabulæ Neurologicæ ad illustrandam historiam anatomicam cardiacorum nervorum, noni nervorum cerebri, glossopharyngæi, et pharyngæi ex octavo cerebri. ” Scarpa, A. 1794 Balthasarem Comini Pub.

12.“The Involuntary Nervous System” Gaskell, W. H.2nd Ed. Longman, Green & Co. 1920

13. “Cardiac anatomy pertinent to the catheter and surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation”. Cox. JL et al J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2020 Aug;31(8):2118-2127. doi: 10.1111/jce.14440.

14. "Minimally Invasive Surgical Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation: A New Look at an Old Problem" Randall K. Wolf, Efrain A. Miranda, Operative Techniques in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 2024,

15. “Correlative Anatomy for the Electrophysiologist: Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation. Part I: Pulmonary Vein Ostia, Superior Vena Cava, Vein of Marshall” Macedo PG, Kapa S, Mears JA, Fratianni A, Asirvatham SJ. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010 Jun 1;21(6):721-30.

16. “Treatment of lone atrial fibrillation: minimally invasive pulmonary vein isolation, partial cardiac denervation and excision of the left atrial appendage” Wolf, R.K. Ann Cardiothoracic Surg. 2014; 3:98-104

17. “Neurocardiology: Anatomical and Functional Principles” Armour, J.A. Institute of HeartMath, Boulder Creek, CA, 2003

18. “The enteric nervous system: a little brain in the gut" Annahazi, A. ∙ Schemann, M. Neuroforum. 2020; 26:31-42

19. “The Little Brain Inside the Heart” Dr. José Manuel Revuelta Soba Professor of Surgery. Professor Emeritus, University of Cantabria, Spain

Images

Image of the CNS - Public Domain. Source: WikipediaCreative CommonsAttribution 4.0 International license.

Autonomic and Somatic Image. Public Domain by Christine Miller. Source: WikipediaCreative CommonsAttribution 4.0 International license.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

- Hits: 1301

During the last year the number of artificial intelligence (AI) anatomical and surgical images found in websites and social media (Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, etc.) has grown exponentially. The same has happened with posts and articles from so-called experts targeting the public, medical students, and health professionals. Unfortunately, many of these have glaring anatomical errors (1). The reason for this trend is an unscrupulous race to obtain an increased number of followers which leads to monetization of a website, posts, individuals, or groups.

The authors using AI prompts that create these images publish them as fast as they are produced without a thought as to the correctness of what’s being created by AI. Their followers, also without a thought or question of the content or image, like, share, copy and distribute these on the Internet. An example is the publication (now retracted) of rat stem cells using AI imagery. The image generated is of such bad taste, yet it was peer-reviewed and published. The image shows a rat with large genitalia. I cannot in good conscience publish the image here. For more information see “Sources” 2, 3 (a newspaper article on the problem), and the publisher's retraction.

Another glaring example is this video that shows the heart valves in action. It is not accurate. The movement and synchrony of the valves is wrong, they do not open, the pulmonary valve, which normally has three leaflets, shows four. The coronary arteries are in the wrong location and there an extra coronary on the right side. No one could live with that aortic valve. Yet, this image has 10.K likes and 2.5K shares! Ignorance is being shared. Just because it looks sexy, it does not mean that it is correct! (1).

The problem is that these websites and images are being used by health care professionals, students, and medical industry training groups without questioning the accuracy of the information being copied and redistributed externally and internally in training documents. This is not an uninformed statement. I have seen it personally, not in one, but in several companies.

The pressure that training groups in the medical arena and in other industries have is to reduce costs and training time. For those of you who know me and whom I have trained, you may recall how two decades ago training for a surgical devices representative could take six, ten weeks, and sometimes longer. I do know of one company that required a six-month internship before considering someone ready! Many of those who underwent this training are today in high-level corporate positions or by now have retired very well.

Today, the race is on to reduce face-to-face training time because it is perceived to be expensive, but the cost of poor and inaccurate training for a company is much, much more expensive! Other trends are the use of computer-based training (reduces cost), and reducing the amount of information passed on to the trainee (reduces time). The interesting situation here is that there are forces within these companies that are uninterested in learning more, just training enough to do a basic job.

Another alarming trend is that knowledge acquired in training is geared toward acing the internal tests (checking the boxes) and not necessarily geared toward working use of that knowledge when interacting with a medical professional.

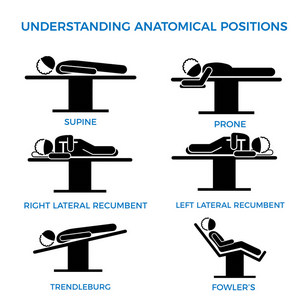

The need to generate training material forces many to copy and paste images and concepts from the Internet. Just because a concept is available on the Internet does not make it correct. In fact, there are many reputable websites and books that have erroneous information. Here is an example from a medical devices company that shows “anatomical positions” (there is only one anatomical position) when the image should be labeled “surgical positions”. If you click on the image you will see a larger image with corrections.

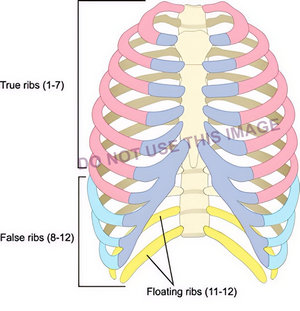

The next image by a reputable medical illustrator shows the groups of ribs, but there is a mistake: False ribs are only 8 – 10, not 8-12! Yet this image is being used for training. I do not know if this image was incorrectly labeled by a third party.

I have seen many companies give a sales representative, manager, engineer, or other employee the responsibility to develop presentations and computer-based training, and what do they do? Go on the Internet for information. Here is where that computer acronym becomes a painful reality: GIGO “garbage in, garbage out”. For me, this is unacceptable, as this could affect a patient!

The only way to ensure the information is correct is to use an expert (but of course that’s not free). This leads to another problem: The Dunning-Kruger effect. This is a phenomenon where some people believe that they are much more competent, knowledgeable, or capable than they really are. Furthermore, they convince their peers and their company of it. David Dunning and Justin Kruger In their 1999 article coined the term “unskilled and unaware of it”, which is sadly becoming commonplace today.

Another example of these AI generated images is this view of the spine, spinal cord and spinal nerves and branches. The zygapophysial joints look fused (they are not), the dural (thecal) sac fills the vertebral canal (it does not), the spinal nerve and its branches are wrong. Interestingly, I did comment on the mistakes in the image to the author. The answer I received was: ”the more easy the illustration, the more the students will get into it. A complicated high info video may scare undergraduate freshers. That's why I post things in simple”. So, is it correct to teach something wrong? Call me old-fashioned, but I do not think so.

I could go on and on with these examples. Case in point: Image 1 is an AI generated image of the vagus nerve. It is wrong on so many levels! Contrast that with image 2, which is a public domain image from the 1794 “Tabulae Neurologicae” by Antonio Scarpa. The arrow shows the right vagus nerve.

Text available online should not be copied without ensuring that it is correct. An example: “The lungs are enclosed by the pleural sacs, which are attached to the mediastinum”. The first part is correct, each lung is contained in a separate pleural sac (only 86% of the time, the rest of us may have a communication between both pleural sacs). But the pleural sacs are not attached to the mediastinum! The mediastinum is a concept, the region between the pleural sacs, not a real structure.

Lastly, there are copyright issues where it has become so simple to highlight, copy, and paste that many do not think twice about using proprietary text and images without considering the consequences of this activity. One of the most used and abused books is Frank Netter’s Atlas of Human Anatomy. You can see it all over the Internet in posts that appear daily. This is a technique to increase traffic and clicks. Just because it was published in one of these social media posts, does not mean that we can freely use it in training materials. This abuse is rampant in social media where so-called experts copy and paste images from books and other websites.

Additionally, these deepfake "experts" are generating click-bait videos that use audio tracks (probably also AI generated from text) scaring and fooling people on social media.

The Internet is an extremely powerful tool, yet it is important to remember that not everything on the Internet is true, accurate, and readily available for copy and paste functions. Not all information should be believed at face value. I sincerely hope that this trend changes.

Why do I think this is so important? In the medical devices industry our first responsibility is to the patient and to be able to provide the best care. A healthy distrust of every bit of information we use, and investing time and resources to attain accuracy will help us toward this objective.

Following are some additional examples, some so fake as to be hilarious, but someone is watching them and believing what they are seeing and hearing.

The first video shows structures inferior to the transverse colon that do not exist, besides that, peristaltic movements are not like that... it looks more like heart contractions! The second video shows a moving thyroid gland and the vascular and nerve structures are all wrong! The third one is ridiculously wrong!! These videos hare captioned in Spanish, but you can find the same in any other language.

Personal note: I have purposely tried to avoid identifying individuals, websites, companies, etc. while writing this article. I have also decided to add this AI generated image to my list of pet peeves.

"The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, and wiser people so full of doubts.”

Bertrand Russel

Sources:

1. “It looks sexy, but it is wrong. Tensions in creativity and accuracy using genAi for biomedical visualization” Zimman, R; Saharan, S; McGill, G; Garrison, L. 2025 https://arxiv.org/pdf/2507.14494

2. “RETRACTED “Cellular functions of spermatogonial stem cells in relation to JAK/STAT signaling pathway” Guo,X; Dong, L; Hao, D. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2024 PDF Link here

3. “AI-generated nonsense about rat with giant penis published by leading scientific journal” The Telegraph, 2024.

4. “Emotionally unskilled, unaware, and uninterested in learning more: Reactions to feedback about deficits in emotional intelligence” Sheldon, O. J., Dunning, D., & Ames, D. R. (2014). Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(1), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034138

5. “Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments” Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

6. “Chapter 5- The Dunning–Kruger Effect: On Being Ignorant of One's Own Ignorance” Olson, HM; Zanna, MP. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (2011) – 44: 247-296 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385522-0.00005-6 (these are snippets, not the whole chapter)

7. "How people are being tricked by deepfake doctor videos on social media" New York Post July 17, 2024

8. "Positioning in Anesthesia and Surgery" Martin, JT; Warner, MA 3rd Ed. 1997 USA W.B. Saunders

9. https://elearningdoc.com/the-hidden-costs-of-inadequate-training/

- Details

In the many years I have lectured for the medical industry, the one word that representatives, managers, engineers, etc. usually do not master is “morbidity”.

In most cases when I ask for a definition of “morbidity” most in the audience try to guess and in the medical arena and medical devices industry guessing is not acceptable. So, I would like to ask those who follow my articles and posts to repost this information so that it is available for as many people as possible. By the way, the most common answer I receive is that "morbidity" means death...not so!!

The term “morbidity” arises from the Latin word morbus which means Ill, sick, or sickly. It has been in use in English for centuries and what today we call “pathology” used to be known as “morbid anatomy”. There are many terms in medical history that included the term “morbid” such as “morbus indecens” (venereal diseases); morbus gallicus (syphilis), “morbus sacer” (epilepsy, the sacred disease), etc.

To be simple, today we use the term “morbidity “to mean “complications”, As an example, when we use the term “postoperative morbidity” what we’re trying to say is simply “postoperative complications”. When you ask what is the morbidity associated with a certain treatment (a new medication, as an example) what we’re trying to say is what are the complications associated with that medication or treatment.

Now, the associated term “comorbidity” causes the same problems. Many think they know its meaning, but they are actually guessing, and it can lead to embarrassing conversations between a medical device representative and a surgeon or physician.

The term comorbidity is a portmanteau (French) word, that is, a word formed by the mixing of parts of two words. In this case, the components are COncommitant (meaning associated) and MORBIDITY, (meaning complications). Simple stated, comorbidity means “associated complications”. As a side note, do not add a hyphen, as in co-morbidity: this is wrong.

There are many portmanteau words in English, such as “brainiac”; “bromance”, “Brexit”, “fog”, etc. For additional portmanteau non-medical words follow this link.

Sources.

1. "The origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, AH 1970

2. "Medical Meanings - A glossary of Word Origins" Haubrich, WS. 1997