Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 1135 guests online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

In the many years I have lectured for the medical industry, the one word that representatives, managers, engineers, etc. usually do not master is “morbidity”.

In most cases when I ask for a definition of “morbidity” most in the audience try to guess and in the medical arena and medical devices industry guessing is not acceptable. So, I would like to ask those who follow my articles and posts to repost this information so that it is available for as many people as possible. By the way, the most common answer I receive is that "morbidity" means death...not so!!

The term “morbidity” arises from the Latin word morbus which means Ill, sick, or sickly. It has been in use in English for centuries and what today we call “pathology” used to be known as “morbid anatomy”. There are many terms in medical history that included the term “morbid” such as “morbus indecens” (venereal diseases); morbus gallicus (syphilis), “morbus sacer” (epilepsy, the sacred disease), etc.

To be simple, today we use the term “morbidity “to mean “complications”, As an example, when we use the term “postoperative morbidity” what we’re trying to say is simply “postoperative complications”. When you ask what is the morbidity associated with a certain treatment (a new medication, as an example) what we’re trying to say is what are the complications associated with that medication or treatment.

Now, the associated term “comorbidity” causes the same problems. Many think they know its meaning, but they are actually guessing, and it can lead to embarrassing conversations between a medical device representative and a surgeon or physician.

The term comorbidity is a portmanteau (French) word, that is, a word formed by the mixing of parts of two words. In this case, the components are COncommitant (meaning associated) and MORBIDITY, (meaning complications). Simple stated, comorbidity means “associated complications”. As a side note, do not add a hyphen, as in co-morbidity: this is wrong.

There are many portmanteau words in English, such as “brainiac”; “bromance”, “Brexit”, “fog”, etc. For additional portmanteau non-medical words follow this link.

Sources.

1. "The origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, AH 1970

2. "Medical Meanings - A glossary of Word Origins" Haubrich, WS. 1997

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

- Hits: 6555

The persistent left superior vena cava (PLSVC) is the most common anatomical variation or anomaly in thoracic anatomy. It is present in 0 .3 to 0 .5% of the general population, but it can be present in 5% to 10% of patients who present some type of congenital cardiac malformation.

The most common presentation of this anomaly is where the PLSVC shares the venous drainage with a normal right superior vena cava. In other cases, the PLSVC is present, but there is total absence of the right superior vena cava. In these cases, the condition can be asymptomatic and can be discovered intra or preoperatively. The PLSVC is shown with a yellow arrow in the accompanying image.

In some cases, the PLSVC opens into the left atrium, causing a right to left cardiac shunt, a condition that is clearly symptomatic.

Embryologically, the development of the (right) superior vena cava begins with a similar counterpart on the left side of the embryo, the left anterior cardinal vein.

The left cardiac horn and left anterior cardinal vein eventually form the coronary sinus while its superior portion obliterates, becomes non- patent and forms the duct of Cuvier and the ligament of Marshall. A portion of the left anterior cardinal vein remains patent and forms the oblique vein of the left atrium (also known as the vein of Marshall). The vein of Marshall is found at the base of the left atrial appendage.

When present, the diameter of the PLSVC is usually quite larger than the average diameter of a normal coronary sinus, and because of the increased flow into the right atrium, the valves of Thebesius (valve at the ostium of the coronary sinus) and the valve of Vieussens (valve found at the end of the great cardiac vein and the start of the normal coronary sinus) are either absent or present with substantial reduction in size.

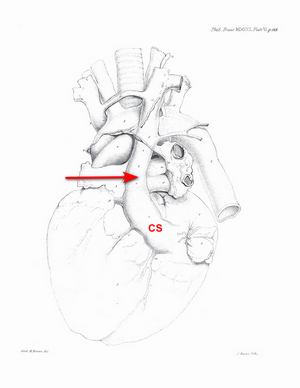

The history of the discovery and description of the PLSVC is not clear. There are many attributions, but what is undeniable is that the first complete and detailed description of this anatomical variation was done by John Marshall in 1850. The following image shows the original drawing (Plate VI) in his article “On the Development of the Great Anterior Veins Man and Mammalia; including an Account of certain remnants of Fœtal Structure found in the Adult, a Comparative View of these Great Veins the different and an Analysis of their occasional peculiarities in the Human Subject”.

While often clinically silent, PLSVC has important implications for central venous access, pacemaker lead placement, and cardiac surgery.

Personal note: My personal thanks to my good friend and contributor to "Medical Terminology Daily", Dr. Randall K. Wolf for the surgical image.

The following YouTube video by Medical Snippet with animations and drawings by Karthik Easvur provides a detailed description of the formation of the superior vena cava and the PLSVC.

Sources:

1. “Persistent left superior vena cava”. Tyrak KW, Holda J, Holda MK, Koziej M, Piatek K, Klimek-Piotrowska W. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2017 May 23;28(3):e1-e4. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2016-084. PMID: 28759082; PMCID: PMC5558145.

2. “Persistent left superior vena cava: review of the literature, clinical implications, and relevance of alterations in thoracic central venous anatomy as pertaining to the general principles of central venous access device placement and venography in cancer patients.” Povoski SP, Khabiri H. World J Surg Oncol. 2011 Dec 28;9:173. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-173. PMID: 22204758; PMCID: PMC3266648.

3. “Absent Right Superior Vena Cava and Persistent Left Superior Vena Cava: An Incidental Finding.” Joshi, Swati, and Ajmer Singh. Annals of Cardiac Anaesthesia, 2nd ed., vol. 26, no. 4, 2023, pp. 433–34, https://doi.org/10.4103/aca.aca_91_23.

4. "Absent right superior vena cava in visceroatrial situs solitus.” Bartram, U., Van Praagh, S., Levine, J. C., Hines, M., Bensky, A. S., & Van Praagh, R. 1983 Am J Card, 52(10), 1262–1268.

5. “Superior vena caval abnormalities: their occurrence rate, associated cardiac abnormalities and angiographic classification in 542 patients” Buirski, G., Jordan, S. C., Joffe, H. S., & Wilde, P. (1986). Cardiovasc Interv Rad, 9(6), 357–362.

6. "Persistent Left Superior Vena Cava with Absent Right Superior Vena Cava" Pate, Y; Gupta, R. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovasc J. 2018. 14:3. 2223-235. DOI: 10.14797/mdcj-14-3-232

7. “On the Development of the Great Anterior Veins Man and Mammalia; including an Account of certain remnants of Fœtal Structure found in the Adult, a Comparative View of these Great Veins the different and an Analysis of their occasional peculiarities in the Human Subject” 1850 Phil Trans R Soc 140:133 - 170. To download this article click here.

Video courtesy of Medical Snippet. The video, animations and drawings are the property of their owners. We encourage viewers to follow and subscribe to their respective YouTube channels.

Image of Marshall's Plate VI modified from the original. Public domain.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

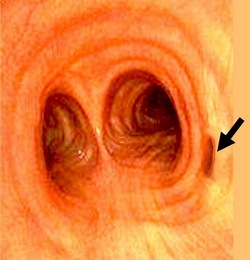

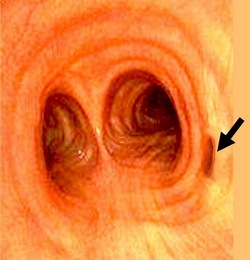

Tracheal bronchus (pig bronchus)

After writing an article on the tracheal bronchus, I was asked to describe the anatomy of the pig (Sus scrofa domesticus) lung and a comparison with the human lung. The function and general structure of the pig lung is similar to the human. Anatomy-wise... there are several differences.

It is important to understand that directional terminology used to describe the anatomy of the pig is different than that used for the human. We use the anatomical position for humans, but as the pig is a quadruped, there is no such position for the pig, and veterinary terminology is used.. For further information on this topic, click here.

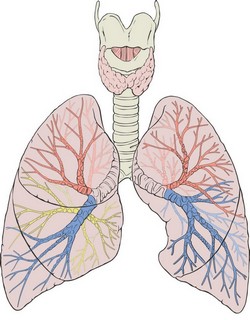

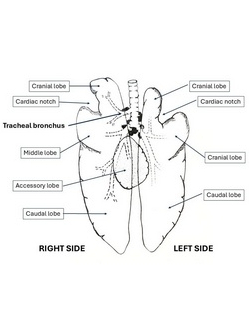

Following are two images. The first one is an anterior view of the human lungs and their tracheobronchial tree. The second image shows a ventral view of the pig tracheobronchial tree and both lungs.

The first difference with the human lung is that there are two cardiac notches, right and left (the left cardiac notch is larger) whereas the human has only one, on the left lung.

The structure of the tracheobronchial tree in both species is similar, with incomplete cartilaginous rings and a posterior (dorsal) membrane that closes both the trachea and bronchi. Similarly, as the bronchial tree is more distal, the cartilaginous rings break up.

The trachea in the human ranges between 10 to 12 centimeters, while in the pig the trachea is longer, between 25 to 30 centimeters. Both bifurcate at the carina into a right and left main stem bronchus. In both species there is a large number of lymphatic nodes at the tracheal bifurcation (carinal nodes) which drain the lungs.

In the pig, the bronchus for the right cranial lobe arises directly from the trachea, and is known as the "tracheal bronchus". This does not normally happen in the human, and when it does it is considered an anatomical variation called a "pig bronchus", "bronchus suis", or "tracheal bronchus", and it can cause serious problems during intubation in surgery.

In the human, there are normally three lobes on the right side (upper, middle, and lower), and two on the left side (upper and lower). Each lobe has its separate lobar bronchus.

The right lung in the pig has 4 lobes: Cranial, middle, caudal, and an accessory lobe that is ventral and is located in the midline. Each lobe has its own separate lobar bronchus.

The left lung in the pig has two lobes: Cranial and caudal. The left cardiac notch splits the cranial lobe in two segments, but since these segments arise from a common bronchus, they are considered one lobe.

Sources:

1. "Essentials of Pig Anatomy" Sack, W.O.; Horowitz, A. 1982 Veterninary Textbooks, Ithaca, New York..

2. “Bronchial tree, lobular division and blood vessels of the pig lung” Nakakuki, S. J Vet Med Sci. 1994 Aug;56(4):685-9.

3. “Bronchial anatomy and single-lung ventilation in the pig” Muton, WG. Can J Anesth 1999 46:7 p701-703

- Human tracheal bronchus endoscopic image modified from the original. Public domain.

- Anterior view of the human lungs and tracheobronchial tree image by . Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustrator, CC BY 2.5 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5>, via Wikimedia Commons.

- Ventral view of the Ventral view of the pig lungs and tracheobronchial tree image by Dr. Miranda, modified from the original. Public domain.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

Tracheal bronchus (pig bronchus)

The tracheal bronchus is a known anatomical variation first described in 1785 by Eduard Sandifort (1742 – 1814), a Dutch physician and anatomist. Sandifort was the first to describe in detail what we know today as the Tetralogy of Fallot, although Nicolaus Steno (1638-1686) mentions the components of this pathology, he did not investigate it in detail as Sandifort did.

It is mostly known as the “pig bronchus” because of its similarity with pig anatomy; it is also called “bronchus suis”. When present, the tracheal bronchus usually arises on the right side of the trachea, about 2 cm. superior to the tracheal bifurcation (carina). The location of the bronchial aperture can vary between the cricoid cartilage of the larynx superiorly, and the tracheal bifurcation inferiorly.

The tracheal bronchus is usually the only airway supplying the upper right lobe of the lung, although it can share the airway with a smaller right upper lobe bronchus. In this case the tracheal bronchus is called “accessory tracheal bronchus”.

In cases where the origin of the tracheal bronchus is higher on the trachea, the trachea may present with distal stenosis. In rare cases, the tracheal bronchus may be found on the left side supplying air to the superior portion of the left lung.

The incidence of a tracheal bronchus varies between 1 to 5%, where the prevalence on the right side is 0.1 to 2% and 0.3 to 1% on the left side. It is sometimes found associated with other congenital abnormalities.

It is usually asymptomatic, but it can be found related to recurrent pulmonary infections, bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis, and partial airway obstruction. It is most often discovered incidentally, usually during the intubation process for thoracic surgery.

Personal note: My thanks to Dr. Randall K. Wolf for suggesting this article.

Sources:

1. “Observationes anatomico-pathologicae” Sandifort, E. (1785). Lugduni Batavorum: Apud S. & J. Luchtmans.

2. “Congenital bronchial abnormalities revisited” Ghaye, B., Szapiro, D., Fanchamps, J. M., & Dondelinger, R. F. (2001). Radiographics, 21(1), 105–119.

3. “Tracheal bronchus: A rare cause of right upper lobe collapse” Ngernchuklin, P., Sumanac, K., & Behrsin, J. (2006).. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia, 53(12), 1227–1230

4. “Tracheal bronchus” radiopedia.org. Elfeky, M. 2023.

5: ”Bronchus suis – Case presentation” radiopedia.org. Ian Bickle.

Image modified from the original, public domain.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

- Hits: 1769

For those who follow this blog or my articles on LinkedIn you know that I have several pet peeves regarding the misuse of medical and anatomical terminology. You can read some of these articles in the following links:

- One of my pet peeves... pronouncing the word “dissection” wrong

- 11+ medical words that are used incorrectly

- Ramus intermedius, a cardiac anatomical variation

- Using vernacular terms as medical terms

- GIGO: The use of artificial intelligence in social media and education. “It looks good, so let’s use it (but it’s wrong)”

Recently, reading an article on Facebook, I realized that there are many people, some of them health care professionals, who use (and teach) anatomical directional terminology incorrectly. The post itself shows an image depicting directional terminology in humans.

The original image is shown here and if you hover your mouse on it you will see my concerns. If you click on it, you will see a larger depiction of these concerns.

1. Dorsal and Ventral and… 2. Caudal and Cranial

These four terms are used by many, referring to the human body in the anatomical position. The fact is that in the human anatomy, the proper terms to use are as follows:

1. Instead of ventral, the proper term to use is anterior.

2. Instead of dorsal, the proper term to use is posterior.

3. Instead of cranial, the proper term to use is superior.

4. Instead of caudal, the proper term to use is inferior.

Let’s look at the etymology behind the terms.

Ventral arises from the Latin [ventrum] and [venter] which means “abdomen” or “belly”. Some contend that the term means “towards the abdomen” and even say that the term is correct because the abdomen is the largest part of the anterior aspect of the body. In any case, never use the term “stomach” to mean abdomen (another pet peeve).

The term dorsal arises from the Latin [dorsum] which means “back”.

The term cranial arises from the Latin [cranium] meaning “skull”. Not mentioned in the image is the term “cephalad” which is Greek [κεφάλι] meaning “head”. The suffix [ad] means “toward”, so cephalad means “towards the head”.

Additional controversy is found with the term “caudal” or “caudad”. It originates from the Latin [cauda] which means “tail”. How can anyone say that the feet are “caudal” when the tail is the coccyx? Despite this, there are many who teach the term caudal and define it as “towards the feet”, even knowing the origin of the term.

The reason for these terms is that they are used in veterinary medicine and embryology. You see, in a quadruped, these four terms apply perfectly as you can see in this image.

The terms “cranial” and “caudal” are also used in embryology. Since the embryo is curved, we need terms that reflect this curvature, and since the upper and lower extremities have not yet developed, the tail is the “end” of the embryo! As for the terms “ventral” and “dorsal”, the image the follows is self-explanatory… the back of the embryo is almost all of it! See the following image:

Controversy also arises from the use of the term “dorsal” to refer to the superior aspect of the foot. It is just a consensus. The inferior aspect of the foot is referred a “plantar”, and “dorsal” was adopted to reflect this opposition.

In the comments to this Facebook article, C. Hartig mentioned “rostral”. The term [rostrum] is Latin and means “beak”. In Roman times the term was used to denote a speaker’s platform, as the dais was usually adorned with eagles that had a pointed beak. Through use, the term “rostrum” was used as “face” (some people have a very pointed nose).

In anatomy we use the term rostral as “face”. The term is used in neuroanatomy and refers to a plane that is transverse to the axis of the Central Nervous System. See the accompanying image. In the spinal cord, the terms “rostral” and “caudal” follows the transverse plane of the body. In the head, the axis of the brainstem changes and now an axial image of the brainstem is angled. In the cerebrum this changes again and now points anteriorly towards the face (or frontal lobe).

This leads to the misuse of the term “axial”. Yes, it can be used as “transverse plane, but only when referring to the body as a whole. This changes when we use the term “axial” referring to an organ or structure. An “axial” image of the heart is different from a “transverse image of the heart.

A word of caution. Because of the importance of embryology in neurogenesis of the nervous system, these embryological terms are used in adult neuroanatomy, Hence the terms "dorsal root ganglion", "ventral horn", ventral root", etc.

3. Sagittal Plane

The term “Axes of the CNS (Dr. Miranda, 1977)” arises from the Latin [sagitta], meaning “arrow”. An arrow would transfix someone from front to back. A sagittal plane is a vertical plane that divides the body into right and left portions. Since a plane has no width (geometrical definition) there are infinite sagittal planes. Only one divides the body into equal right and left portions. This is the midsagittal plane or median plane.

The image is correct in the sense that the median plane is one of many sagittal planes, but this representation forces many students to misuse the terms. If it is a median or midsagittal image, say so.

Disclaimer: I do not know the origin of the original image in the Facebook post, whether it is copyright-free or not. I used it because it has been posted publicly. All other images in this article are personal, copyright-free, or proper attribution have been posted as required by copyright law.

Sources:

1. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

2. “The Origin of Medical Terms” Skinner HA 1970 Hafner Publishing Co.

3. "Medical Meanings, A Glossary of Word Origins" Haubrich, W.S. 1997. American College of Physicians, Philadelphia, PA.

4. "Elementos de Neuroanatomía" Fernandez, J.; Miranda, EA.

5. "Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary" 28th Ed. W.B. Saunders. 1994

6. "Medical Terminology; Exercises in Etymology" Dunmore CW, Fleischer RM 2nd Ed. 1985

7. "Medical Meanings; A Glossary of Word Origins" Haubrich, WS. Am Coll Phys 1997

8. "Lexicon of Orthopædic Terminology" M. Diab. 1999. Amsterdam Hardwood Academic Publishers.

9. "Gray's Anatomy" 38th British Ed. Churchill Livingstone 1995

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

Peripheral nerve injuries can result from trauma, compression, thermal damage or systemic diseases, and their classification is essential for diagnosis, management, and prognosis. Three key terms are used to describe the severity and nature of these injuries: neurapraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis. They describe the structural and functional integrity of nerve fibers after injury. The etymology of these terms derives from the Greek language.

These terms were initially proposed by Sir Herbert John Seddon (1903 – 1977), an English anatomist and orthopedic surgeon who published his initial findings in 1943, followed by Sir Sydney Sunderland (1910 – 1993), an Australian orthopedic surgeon who published a revised classification in 1951. The terms coined by Seddon and Sunderland and their classification system into 5 Grades of Nerve Injury remain central to the treatment of nerve injuries today.

Neurapraxia:

Neurapraxia represents the mildest form of nerve injury. It is characterized by a temporary block of nerve conduction without axonal disruption. Recovery is typically complete and occurs within days to weeks.

• No structural damage to the axon or surrounding connective tissue.

• Localized demyelination may occur, leading to a conduction block.

• Commonly results from compression or mild blunt trauma (e.g., “Saturday night palsy” or a "transient ulnar nerve palsy").

The term is derived from the Greek [νεῦρον] meaning “nerve” and [πρᾶξις] (praxis) meaning “action”. In medical terminology “a” or “an” means “without” or “absence of”. Thus, the word is constructed as [neur]-[a]-[praxia] meaning “absence of nerve function”.

Axonotmesis

Axonotmesis is a more severe injury in which the axon is damaged, but the surrounding connective tissue structures (endoneurium, perineurium, and epineurium) remain intact. Wallerian degeneration occurs distal to the lesion, and axonal regeneration following the intact connective tissue channels can allow for not only nerve regeneration but regain of function of the damaged nerve. This is the mechanism of action of cryoneurolysis devices used in surgery.

• Axonal continuity is lost, but the scaffolding remains.

• Regeneration can occur at a rate of approximately 1–3 mm/day.

• Often seen in crush injuries or prolonged compression.

The term is derived from the Greek [ἄξων] meaning “axis” and [τμῆσις], meaning “division” or “cut”. Axonotmesis means “division (cutting) of the axon.”

Augustus Volney Waller (1816 – 1870)

Neurotmesis

Neurotmesis is the most severe form of nerve injury. It involves complete disruption of the axon and surrounding connective tissue, as would happen when a nerve is transected or avulsed. It results in permanent loss of function, since when the axons start to regrow, there are no connective tissue “tunnels” to guide the growing axon to their terminal connections. One of the problems that may happen is the formation of a neuroma or neurinoma at the site of nerve transection.

The only way to attempt to restore function is with surgical intervention bringing the cut ends of the nerves together, sometimes using microsurgery. The results of surgery are not always optimal

• Wallerian degeneration occurs distal to the injury.

• Regeneration is not possible without surgical repair.

• Typically is the result from lacerations, severe traction injuries, or penetrating trauma.

The term is derived from the Greek [νεῦρον] meaning “nerve” and [τμῆσις] meaning “division” or “cut”. Neurotmesis thus translates to “division of the nerve.”

Accurate classification of nerve injuries can help guide prognosis and treatment:

• Neurapraxia: Managed conservatively with physical therapy and observation.

• Axonotmesis: May require surgical exploration if function does not return within expected time frames.

• Neurotmesis: Early surgical intervention is usually necessary to restore any function.

Note: The term “Wallerian degeneration” is associated eponymically with Augustus Volney Waller (1816 – 1870), an English physiologists know for his work on nerve injury and regeneration.

Personal note: Most people talk about "peripheral nerves", as if "central nerves" existed. This is not so. Within the Central Nervous System (CNS) the bundles of axons have different names such as "fascicles" (fasciculus lenticularis), tracts" (spinothalamic tract), lemniscus (medial lemniscus), etc. These central bundles of axons form structures that themselves have separate names, such as the corpus callosum, internal capsule, external capsule, anterior commissure, etc. All of these structures lack a well formed connective tissue wrap, which is the reason why transection of these structures usually does not allow recovery, such as in the case of spinal cord transection.

Nerves, which are only found in the Peripheral Nervous System (PNS). do have a well-formed connective tissue wrap formed by the endoneurium, perineurium, and epineurium. The presence of these connective tissue structures is what allows for nerve regeneration and recuperation of functionality.

To be precise then, using the term "peripheral nerve" is redundant, as all nerves are peripheral! Dr. Miranda

Sources

1. Seddon H. Three Types of Nerve Injury. Brain. 1943;66(4):237-88. doi:10.1093/brain/66.4.237

2. Seddon H, Medawar P, Smith H. Rate of Regeneration of Peripheral Nerves in Man. J Physiol. 1943;102(2):191-215. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1943.sp004027

3. Sunderland S. A Classification of Peripheral Nerve Injuries Producing Loss of Function. Brain. 1951;74(4):491-516. doi:10.1093/brain/74.4.491

4. O'Brien, M. D., & Wade, D. T. (1992). Neurological rehabilitation. Chapman and Hall.

5. Liddell, H. G., & Scott, R. (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford University Press.

6. "The Origin of Medical Terms" Skinner 1970

7. "Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary" 28th Ed. W.B. Saunders. 1994

8. “Stedman’s medical eponyms” Farbis, P; Bartolucci, S. Williams & Wilkins 1998

9. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/sunderland-classification-of-nerve-injury

10. " Correlative Neuroanatomy and Functional Neurology" Chusid, Joseph. Lange Medical Publications

The image of H.J. Seddon is an AI composite of the few images and portraits available. Courtesy OpenAI.