Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 720 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Young surgeons today use surgical staplers without a thought as to the history of the development of these surgical devices. The same is true for many who work in the medical devices (surgical staplers) industry. I have worked as a consultant and a trainer for the stapler industry both with Ethicon Endosurgery (today Ethicon, stapling division) and the United States Surgical Corporation (today Medtronic, stapling division) and developed a special interest in the medical history related to the origin, research, and development of surgical staplers.

The history of surgical stapling is quite interesting and has many characters, starting with the early works of Humer Hutl. There are whole books dedicated to this topic.

It cannot be denied that one of the main drivers of surgical stapling in the United States was Dr. Mark M. Ravitch (1910-1989). History tells us that he saw these staplers in action being used by Dr. Nikolai Mikhailovich Amosov (1913–2002) during a visit to the Thoracic Surgical Institute in Kiev in September 1958. Kiev was then part of Russia (then called the USSR).

What I did not know is that Dr. Ravitch had his notes typewritten, and those loose leaf notes are now part of my library in a binder.

The notes in this binder are the carbon copies in onionskin paper of notes typewritten personally by Dr. Mark. M. Ravitch during his trip to the USSR in September 1958. According to his family, Dr, Ravitch had notoriously bad handwriting and he liked to maintain records of his work, so he was a very fast typewriter. He used his personal typewriter and he traveled everywhere with it even during his military service in WWII.

The original notes were bound in a book (also in my collection) and gifted by Dr. Ravitch to his parents. Unfortunately, the paper he used for the originals was not acid-free and the pages in this unique book are slowly crumbling and some of them are today unreadable. Thankfully, the carbon copies are acid-free, and the pages have been carefully scanned in TIF and PDF format by David M. Klein and then placed in separate plastic sleeves for preservation in a binder that is now in my library.

After Dr. Ravitch’s parents passing, both these notes were in the library of his son, Michael M. Ravitch, Ph.D. Michael lent these notes to Dr. Felicien Steichen (1926 – 2011) , who after a time returned the notes with a letter, also included in this binder. In this letter Dr. Steichen says that these notes should be preserved for future research, even mentioning Leon Hirsch (CEO of the United States Surgical Corporation) to support this endeavor.

Michael Ravitch’s widow, Myrnice Ravitch contacted me in 2017 because of my interest in medical history and the life and work of Dr. Ravitch. She donated some books that were in Dr. Ravitch’s library. In early 2024, and with the blessing of Dr. Ravitch’s daughter Binnie and the rest of the Ravitch family, they donated these notes that are now part of the history of surgical stapling and are today part of my library.

In a separate article I will present some of the actual notes regarding surgical stapling, although these notes also include invaluable observations on medicine and surgery in the USSR and Dr. Ravitch’s comments on the Russian culture and people at the time. Keep in mind that Dr. Ravitch’s parents where Russian immigrants and he was fluent in Russian.

In the future, and following Dr. Steichen’s suggestion, I will try to publish a book with these notes along with additional notes on Dr. Ravitch’s trip to China in 1983

Note: The photograph of Dr. Asomov was taken by Dr. Ravitch, but it has since degraded, so it was enhanced using Winxvideo AI.

Note: Dr. N.M. Amosov had an incredible surgical career and recognized with medals and honors. The Institute where Dr. Ravitch saw him operate with surgical staplers is today known as the Amosov National Institute of Cardiovascular Surgery in Kiev, Ukraine.

Sources:

1. "Current practice of surgical Stapling" Ravitch, MM; Steichen, FM; Welter,W. 1991 Lea & Ferbiger USA

2. "Stapling in Surgery" Ravitch, MM; Steichen, FM.1984 Year Book Medical Publishers USA.

3. "Surgical Rounds" Edition dedicated to Dr. M.M. Ravitch May 1990

4. "Notes by Dr. Mark Ravitch on Trip to Russia - September 1958" Personal notes, unpublished.

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

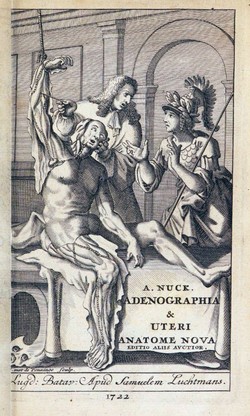

Anton Nuck (1650-1692), a Dutch surgeon and anatomist used several forms for his name such as Antonio Nuck, Anton Nuck, Antonii Nuck, and Antonius Nuck van Leyden. Born in Harderwijk, Netherlands, he moved to Leyden in South Holland, where he studied medicine at the University of Leyden. He received his doctorate in February 1677 with this thesis “De Diabete”.

In 1683 he became a reader (lecturer) of anatomy and surgery at the Collegium Anatomicum Chirurgicum, in Haag (The Hague, Netherlands). He returned to his alma mater in Leyden, where the was appointed to the chair of Medicine and Surgery.

Nuck is known today for the first description of the processus vaginalis, a peritoneal evagination thar runs lateral to the gubernaculum into the inguinal canal in the fetus, both male and female, terminating in the labioscrotal fold, an area that will become the scrotum in the male or the labium majus in the female. This canal is known eponimycally today as the "Canal of Nuck"

The processus vaginalis in the male runs lateral to the vas deferens into the scrotum. The processus vaginalis in normally closed, but if it stays patent, it becomes a passageway for abdominal contents into the scrotum, setting the stage for an indirect inguinal hernia.

In the female the processus vaginalis runs lateral to the round ligament of the uterus. Since the round ligament ends in the labium majus, a patent processus vaginalis sets the stage for an indirect inguinal hernia that bulges into the labium majus (see figure 4 in Source 1- WARNING the image depicts external female genitalia)

Before Nuck, it was argued that females could not have inguinal hernias. In 1691 Nuck published his book "Adenographia Curiosa & Uteri Foeminei Anatome Nova", where he showed that indeed some females could indeed have hernias. For additional information on the canal of Nuck and the text in the book, click here.

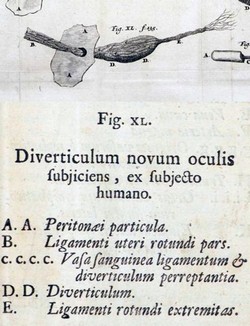

Chapter 10 of this book is entitled “De Peritoneai Diverticulis Novis” (On a New Peritoneal Diverticulum”. Not only Nuck described the processus vaginalis, but he described a pathology today known as “Nuck’s cyst” or “Nuck’s hydrocele”, a cyst within Nucks’ canal. The images above show the title page of his book "Adenographia Curiosa & uteri foeminei anatome nova" and a composite image of plate XL and text. This book was dedicated to the mainly to the topic of lymphatic vessels. The discovery of a patent processus vaginalis was not its intent, but when he found it, he added it to his book. The text on image XL reads "diverticulum novum oculis subjiciens, ex subjecto humano" that can be freely translated as "On a new opening, seen with our eyes in a human subject"

Because of laparoscopic and robotic surgery that requires a pneumoperitoneum, an undiagnosed patent canal of Nuck can lead to a pneumatocele or pneumolabium (See Sources 6)

Besides general surgery, Anton Nuck practiced dentistry and ophthalmic surgery, being the first one to perform a paracentesis for hydrophthalmia (glaucoma) to reduce the pressure inside the eye. He also performed the first recorded vitrectomy. He studied the salivary glands and called the process sialography.

Sources:

1. “Quiste del Conducto de Nuck: una Patología Vulvar Poco Frecuente” Nuñez, JT; Virla, Ln, Delgado del Fox, MD; Gonzalez, A. Rev Obstet Ginecol Venez v.66 n.1 Caracas mar. 2006

2. “Revisiting the clinico-radiological features of an unusual inguino-labial swelling in an adult female” Vinoth, T; Lalchandani, A; Bharadwaj, S; Pandya, B. 2022. International Journal of Surgery Case Reports, 98(Complete)

3. “Early Descriptions of Vitreous Surgery” Grzybowski, A. & Kanclerz, P. (2021) Retina, 41 (7), 1364-1372.

4. The Origin of Medical Terms" Skinner 1970

5. "The cyst of the canal of Nuck: a great mimicker of groin hernia in female" Ben Ismail, I., Sghaier, M., Rebii, S., Zeznaidi, H. and Zoghlami, A. (2024) ANZ Journal of Surgery

6. "Unilateral Vulvar Pneumatocele (Pneumolabium) Diagnosed during Robotic Hysterectomy" Zoorob, D; Spalsbury, M;Slutz, T; et al. (2019) Case Reports in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2019, 8106451

7. "A Family of Early English Oculists (1600-1751), With a Reappraisal of John Thomas Woolhouse"Leffler CT, Schwartz SG. (2017) Ophthalmol Eye Dis.

Anton Nuck's portrait in the public domain, courtesy of the Universiteit Leiden Digital Collections.

Images from "Adenographia Curiosa", public domain, courtesy of Archive.org.

- Details

UPDATED:The [musculi levator labii superioris alaeque nasi] is one of the superficial muscles of expression found in the face. It is a small bilateral muscle found at the angle of the nose and its function is to elevate the superior lip and the side ("wing") of the nose, slightly opening or "flaring" it. When both of these muscles are activated the facial expression attained is called a "snarl".

Its name is Latin and can be loosely translated as the "muscle that lifts the upper lip and the wing of the nose". The muscle attaches to the superior frontal process of the maxilla and inserts into the skin of the lateral part of the nostril and upper lip.

This muscle has two components, one superficial and the other deep. From the insertion point (see red arrow in accompanying image), the deep muscular fibers insert in the skin of the posterior aspect of the nasal wing. The external muscle fibers cross superficially over the orbicularis oris muscle and insert in the deep skin of the upper lip towards the lip anle.

My friend Dr. Elizabeth Murray calls it "a small muscle with the longest name in human anatomy". Fact is, I think she is right! It is worse in Spanish, where the name of the muscle is "músculo elevador común del ala de la nariz y del labio superior"!

Image modified from the original. Public Domain. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

I recently added a new book to my library. It is in Spanish and titled "La Forma Humana de la Línea", which can be loosely translated to "The Human Form of the Line", referring to the hand-drawn images of human skeletal anatomy in the book.

"La forma humana de la línea" Katherine Estrada Suazo. ISBN 9789564021898, 2020. América Impresores. Valdivia, Chile

This is an extraordinary book that depicts in 90 pages and 40 plates the human bony anatomy in beautiful detail using a technique described by Leonardo Da Vinci in his “Trattato della Pittura” (A Treatise on Painting), chapter CXXVI. The author, Katherine Estrada Suazo, draws in hyperrealist detail single bones, a full skeleton, fetal skeletons in a seldom seen detail.

The introduction, the words of the artist, the analysis of Leonardo Da Vinci's technique, and the closing comments are a rare form of high level prose with mastery of the Spanish language that reads almost like poetry.

The book itself is a printing marvel. An uncommon large size (9½ by 15¾ inches/24 by 40 cm.), in a high quality acid-free heavy paper, with beautiful typesetting. The book also includes one large insert measuring 29½ by 9 inches (75 by 23 cm).

This work was supported by Morphology Professor, Patricia Hernández Coliñir at the Anatomy Unit of the Medical School of the Universidad Austral de Chile in the city of Valdivia, where it was printed by the América Impresores printing press. The author also received support from the Chilean government through the Regional FONDART (Regional Ministerial Secretary of Culture, Arts and Heritage). As far as I understand, this book is not for sale, which makes it a rare book.

I became aware of this book at the XLIII Annual Chilean Meeting of Anatomy, where I was invited to present the conference I delivered initially in May 2023 at the University of Antwerp, Belgium. An anatomy professor of the Universidad Austral de Chile, Ana Barriga K., had a copy of the book that was gifted to Dr. Carlos Machado, a good friend and famous medical illustrator of Netter’s Anatomy Atlas.

The road to obtaining the copy of the book included contacting the author and with the help of Professor Barriga, and a friend from Chile, the book went from Valdivia (Chile) to Santiago (Chile), to Mexico, and the US. This copy is dedicated by the author as follows: “Dedicated to Dr. Efrain Miranda. Signed in Valdivia, June 2024”, followed by her signature.

In a recent conversation with the author, she stated that "restricting access to this publication was never my intention", and although having the signed book for me is very important, Ms. Estrada has authorized the open download of the digital edition of the book in PDF format, which you can download here. (19 Mb)

Personal remark: As a side note, the city of Valdivia in Chile, where this book was designed and printed, is the city where my mother was born. Dr. Miranda

Lámina1: Cráneo, vista súperolateral

Recientemente agregué un nuevo libro a mi biblioteca. Está en español y se titula "La Forma Humana de la Línea", en referencia a las imágenes dibujadas a mano de la anatomía esquelética humana que aparecen en el libro.

"La forma humana de la línea" Katherine Estrada Suazo. ISBN 9789564021898, 2020. América Impresores. Valdivia, Chile

Este es un libro extraordinario que describe en 90 páginas y 40 láminas la anatomía ósea humana con hermoso detalle utilizando una técnica descrita por Leonardo Da Vinci en su “Trattato della Pittura” (Tratado sobre la pintura), capítulo CXXVI. La autora, Katherine Estrada Suazo, dibuja con detalles hiperrealistas huesos individuales, un esqueleto completo y esqueletos fetales con un detalle pocas veces visto.

La introducción, las palabras del artista, el análisis de la técnica de Leonardo Da Vincy y los comentarios finales son una forma poco común de prosa de alto nivel con dominio del lenguaje español que se lee casi como poesía.

El libro en sí es una maravilla de impresión. Un tamaño grande poco común (9½ por 15¾ pulgadas/24 por 40 cm.), en un papel pesado libre de ácido de alta calidad, con una hermosa composición tipográfica. El libro también incluye un inserto grande que mide 29½ por 9 pulgadas (75 por 23 cm).

Este trabajo fue apoyado por la Profesora de Morfología, Patricia Hernández Coliñir en la Unidad de Anatomía de la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad Austral de Chile en la ciudad de Valdivia, donde también fue impreso por la imprenta América. El autor también recibió apoyo del gobierno de Chile a través del Fondart Regional (Secretaría Regional Ministerial de Cultura, las Artes y el Patrimonio). Según tengo entendido, este libro no está a la venta, lo que lo convierte en un libro raro.

Me enteré de este libro en la XLIII Reunión Anual Chilena de Anatomía, donde me invitaron a presentar la conferencia que di inicialmente en mayo de 2023 en la Universidad de Amberes, Bélgica. Una profesora de anatomía de la Universidad Austral de Chile, Ana Barriga K., tenía una copia del libro que fue obsequiada al Dr. Carlos Machado, un buen amigo y famoso ilustrador médico del Atlas de Anatomía de Netter.

El camino para obtener la copia del libro incluyó contactar al autor y con la ayuda de la profesora Barriga y un amigo de Chile, el libro viajó desde Valdivia (Chile) a Santiago (Chile), a México y a los Estados Unidos. Este ejemplar está dedicado por la autora de la siguiente manera: “Dedicado al Dr. Efraín Miranda. Firmado en Valdivia, junio de 2024”, seguido de su firma.

En una reciente conversación con la autora, ella afirmó que “nunca fue mi intención restringir el acceso a esta publicación”, y aunque tener el libro firmado para mí es muy importante, la autora ha autorizado la descarga abierta de la edición digital del libro en formato PDF, que pueden descargar aquí. (19 Mb)

Observación personal: Como nota al margen, la ciudad de Valdivia en Chile donde se diseñó e imprimió este libro, es la ciudad donde nació mi madre. Dr. Miranda.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

During one of many trips this year, I found myself with a free day in Boston, Massachusetts. Had a recommendation to try and visit the Ether Dome, which I did, and it was an interesting, although short, experience.

The Ether Dome is the name given by the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) to the first operating room of the MGH and it is located under the dome at the top of the Bullfinch Building, named after its architect Charles Bullfinch (who later became one of the architects for the USA Capitol). The reason for the location of the operating room is that there is a large skylight that provided the light for the operations.

The operating room was in service between 1821 and 1867 and over 8,000 operations were performed here. It was later used as a storage are, a nurse’s dormitory, a dining room, and today as a teaching auditorium. It still has the arrangement of a semicircular staired pavilion, as in the early days of the operating room. The Ether Dome was designated a National Historic Site in 1965.

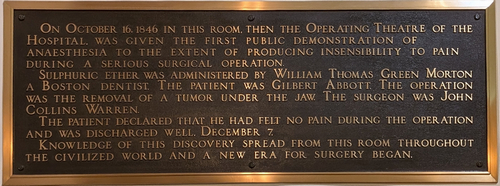

The reason for the name Ether Dome is that in this location, on October 16, 1846, anesthesia was used successfully for the first time. The surgeon was John C. Warren, one of the MGH’s founders. The anesthesiologist was William T. G. Morton, a dentist. The patient was Gilbert Abbott. The operation was the excision of a neck tumor. Upon waking up, the patient said that he had felt no pain.

This event was so revolutionary that painting and images have bee created all over to remember the occasion. One of most creative was the work done for a mural called “Ether Day, 1846” The artists were Warren and Lucia Prosperi, who in 2000-2001 took photographs of surgeons and administrators at MGH in period clothing in different poses to recreate the event of the first use of anesthesia. An oil painting of the mural can be seen at the Ether Dome. If you are interested in visiting the MGH, I recommend planning your visit with the Paul S. Russel Museum of Medical History and Innovation. The museum itself is worth visiting. If you want, the Russel Museum has a virtual tour of the Ether Dome and the Hospital, click here.

Since the Ether Dome is an active teaching auditorium, it is not always available for visitors, to it is good to call ahead, I did not, and was lucky to enter the auditorium prior to a welcome meeting for first year medical students. What an historical location to begin your medical career!

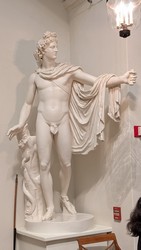

The Ether Dome houses a plaster cast of a Roman statue, the Apollo Belvedere, an Egyptian mummy, and an old human skeleton used for teaching.

A large plaque on the wall reads: ” On October 16, 1846 in this room, then the operating theatre of the Hospital, was given the first public demonstration of Anæsthesia to the extent of producing insensibility to pain during a serious surgical operation. Sulphuric ether was administered by William Thomas Green Morton, a Boston dentist. The patient was Gilbert Abbott. The operation was the removal of a tumor under the jaw. The surgeon was John Collins Warren.

The patient declared that he had felt no pain during the operation and was discharged well, December 7. Knowledge of this discovery spread from this room throughout the civilized world and a new era for surgery began.”

Here is a photograph of a later operation in 1847 where Morton and Warren can be seen.

I have written several articles about this topic, the event, and its protagonists. Here are some of the links:

- Anesthesia

- The first use of anesthesia in surgery

- William T.G. Morton

- Oliver W. Holmes Sr. (who coined the term “anesthesia”)

Note: Ether Dome Skylight image. Ravi Poorun [oddityinabox] CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain

- Details

John Marshall (1818 – 1891)

The ligament of Marshall (LOM) is the embryological remnant of the sinus venosus and left cardinal vein. It contains fat, fibrocellular tissues, blood vessels, muscle bundles (bundles of Marshall), autonomic nerve fibers, and some ganglia corresponding to the ganglionated plexuses (plexi) of the heart.

It was first described by John Marshall (1818-1891) in an 1850 paper titled “On the Development of the Great Anterior Veins Man and Mammalia; including an Account of certain remnants of Fœtal Structure found in the Adult, a Comparative View of these Great Veins the different and an Analysis of their occasional peculiarities in the Human Subject”. In this paper, Marshall makes a detailed embryological description of the structures that derive from the left cardinal vein in the human and adds comparative anatomy with other mammalian species.

The left cardinal vein, which originally enters the left side of the sinus venosus, regresses and modifies leaving the following structures in the adult: From superior to inferior they are the brachiocephalic vein, the obliterated duct of Cuvier, the oblique vein of the left ventricle, and the coronary sinus.

The embryological remnant of the left cardinal vein closes and forms a fibrous cord known as the “duct of Cuvier” (named a after French anatomist and naturalist, Baron de la Cuvier (1769 – 1832)). As this fibrous cord crosses the gap between the left pulmonary vein and the left superior pulmonary vein, the visceral pericardium creates a fold over it; that fold is the ligament of Marshall.

In his paper John Marshall calls it the “vestigial fold of the pericardium”. He describes in this fold “a duplicature of the serous layer of the pericardium, including cellular and fatty tissue, the vestigial fold contains some fibrous bands, small blood-vessels and nervous filaments” …” in the interval between the pulmonary artery and vein”.

The image shows the ligament of Marshall (yellow arrow), the left pulmonary artery (LPA), and the left superior pulmonary vein (LSPV). Click on the image for a larger depiction.

Marshall continues his description as the LOM descends toward the heart and states that there is a portion of the left cardinal vein that is total obliterated and sometimes “wanting”. This is the obliterated portion of the duct of Cuvier, which he does not specifically describes in the LOM. In some cases, Marshall says that the duct is absent and replaced by some whitish fibrous streaks crossing the base of the left pulmonary veins. Today we call this the “obliterated portion of the vein of Marshall”.

He then continues describing a small vein that continues towards and opens in the superior aspect of the coronary sinus. This is the patent portion of the duct of Cuvier, and he calls this structure the “small oblique auricular vein”. Today we call this the “oblique vein of the left atrium” or eponymically, the “vein of Marshall”. The coronary sinus is the end portion of the left cardinal vein.

Contemporary studies on the structure of the LOM have described autonomic nerve fibers and aggregations of neuronal bodies (ganglia) on and around the LOM. Also, cardiac musculature extending from the left atrium, and the coronary sinus over the root of the vein of Marshall have been described (bundles of Marshall).

In some cases, the left cardinal vein does not regress and presents in the adult as a “persistent left superior vena cava”. In this case there is no obliterated duct of Cuvier, the oblique vein of the left atrium and coronary sinus are enlarged, and the venous blood from the head and the left upper extremity drains through the coronary sinus into the right atrium. The following image shows a persistent left superior vena cava (yellow arrow), the left atrial appendage (LAA), the left pulmonary artery (LPA), and the left superior pulmonary vein (LSPV). Click on the image for a larger depiction.

Because of the autonomic nerve fibers and ganglia involved, the LOM (and coronary sinus) have been described as being one of the potential foci for atrial fibrillation (AFib) and has become a target for ablation in AFib surgical procedures.

Personal note: My personal thanks to my good friend and contributor to "Medical Terminology Daily", Dr. Randall K. Wolf for the surgical images.

Sources:

1. “On the Development of the Great Anterior Veins Man and Mammalia; including an Account of certain remnants of Fœtal Structure found Adult, a Comparative View of these Great Veins the different and an Analysis of their occasional peculiarities in the Human Subject” Marshall, J. 1850 Phil Trans R Soc 140:133 – 170

2. “The ligament of Marshall: a structural analysis in human hearts with implications for atrial arrhythmias” Kim, D, Lai, A, Hwang, C. et al. JACC. 2000 Oct, 36 (4) 1324–1327.

3. “Myocardium of the Superior Vena Cava, Coronary Sinus, Vein of Marshall, and the Pulmonary Vein Ostia: Gross Anatomic Studies in 620 Hearts” DeSimone CV, Noheria A, Lachman N, Edwards WD, et al. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012 Dec; 23(12)

4. “Correlative Anatomy for the Electrophysiologist: Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation. Part I: Pulmonary Vein Ostia, Superior Vena Cava, Vein of Marshall” Macedo PG, Kapa S, Mears JA, Fratianni A, Asirvatham SJ. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010 Jun 1;21(6):721-30.

5. “"Human Embryology" WLJ Larsen 1993 Churchill Livingstone

6. “Langman's Medical Embryology" Sadler, T.W. 7ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1995.

7. "Vascular Surgery: A Comprehensive Review" Moore, Wesley S. USA: W.B. Saunders, 1998.

8. Portrait of J. Marshall by Alphonse Legros, Courtesy of Wikipedia. Public Domain.