Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 832 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

The medical term embolus arises from the Greek [έμβολο] (pronounced émvolo) meaning "a plug", or "a plunger". This Greek term was later adopted in Latin [embolus] and is used in this unchanged form today. The plural for embolus is [emboli].

In medicine, the term embolus usually refers to a free blood clot that travels down the bloodstream. When in the veins, emboli will travel easily to and through the heart. This is because veins increase in diameter towards the heart. The opposite happens in arteries. Free blood clots (emboli) that passed through the heart with no problem now enter the pulmonary arteries whose branches get smaller and smaller until the emboli plug the arterioles, and now the patient has a pulmonary embolism.

When thrombi are generated in the heart, they are usually generated in the left atrial appendage in cases of arrhythmia or atrial fibrillation. If these thrombi embolize, that is, they become free, these now emboli will continue downstream in the arteries and progressively smaller arterioles until they are bigger that the vessel and plug it, cutting off blood supply. This condition can cause an infarction, also known as a stroke.

The term embolus can also refer to liquids. fat, or gases that enter the blood stream and are not diluted.

The first use of this term in modern medicine was by Virchow in 1846 in his paper "On the Occlusion of the Pulmonary Arteries"

The root term for this word is [-embol-]. Examples of its use are:

• Embolism: The suffix [-ism] means "behavior" or "pathology".

• Thromboembolism: A combination of root terms; the root term [-thromb-] means "fixed clot" and [-embol] means "a free clot". A condition or presence of both trombi and emboli.

Sources:

1. "The Origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, HA 1970 Hafner Publishing Co.

2. "Medical Meanings - A Glossary of Word Origins" Haubrich, WD. ACP Philadelphia

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

- Hits: 8308

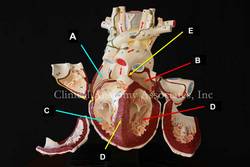

[UPDATED] The term [atrium] is Latin, its plural form is [atria]. The atrium was the center hall of a Roman home, around which the rest of the rooms opened. Since the atrium was the first area of the house that was entered once passing through the front door, the term [atrium] has been used to describe the "entrance hall', such as the atrium of a hotel. The atria are the two superior chambers of the heart. (see image, items "A=right atrium" and "B=left atrium")

[UPDATED] The term [atrium] is Latin, its plural form is [atria]. The atrium was the center hall of a Roman home, around which the rest of the rooms opened. Since the atrium was the first area of the house that was entered once passing through the front door, the term [atrium] has been used to describe the "entrance hall', such as the atrium of a hotel. The atria are the two superior chambers of the heart. (see image, items "A=right atrium" and "B=left atrium")

An interesting question is why are the atria called so, since they are part of the heart, and not just the entrance?. The reason is that early anatomists considered the heart to be composed only by the ventricles. The atria were then chambers where blood would wait before entering the "heart proper", ergo [atria].

Each atrium has a smooth wall (sinus venarum) and a muscular extension akin to a closed-end bag. These are the atrial appendages or auricles. Anatomically they are quite different. The right atrial appendage communication or opening to the right atrium is wide and allows blood to easily flow from and to the atrium. On the contrary, the left atrial appendage has a very small opening (ostium) and its morphology is convoluted with lobulations and a complicated mesh of atrial muscle wall.

The very structure of the left atrial appendage is quite conducive to the formation of clots in atrial fibrillation (AFib). These anchored clots (thrombus/thrombi) can detach and become free clots (embulus/emboli) that will enter the blood stream, pass into the left ventricle, then though the aortic valve, and then pass into the ascending aorta and main circulation. Unfortunately, two of the first arteries that arise from the aorta are the common carotid arteries that take blood to the brain and these thrombi can cause a brain stroke.

Personal note: On November 7, 2023 Dr. Randall K. Wolf invited me to a seminar where we reviewed the anatomy of the left atrial appendage, the problems it can cause in atrial fibrillation as a cause for stroke, and the reasons for its exclusion in AFib surgery.

Image property of:CAA.Inc.. Photographer:D.M. Klein

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

[UPDATED] What is atrial fibrillation?

Atrial fibrillation (AFib) is one of the most common heart conditions, affecting 4% of the adult population. Characterized by a rapid, irregular heartbeat, AFib is largely due to abnormal electrical impulses that cause the atria of the heart to quiver when it should be beating steadily.The atria are the two upper chambers of the heart.

Because of this quivering action, blood flow is reduced and is not completely pumped out of the atria. This negatively impacts cardiac performance and also allows the blood to pool and potentially clot. These clots, if freed, can enter the systemic circulation and cause a stroke.

At rest, a normal heart rate is approximately 60 – 100 beats per minute. In a person with AFib, that heart rate can increase to 180 bpm or even higher. Thorough testing by your health care provider can spot abnormalities in the heart's rhythm before any obvious symptoms are noticed.

What are the symptoms?

Whether it is caused by stress, exercise, or too much caffeine, most people experience rapid heart from time to time. Most cases are harmless, but AFib is a serious medical condition that may often be long lasting. Some people with AFib experience no symptoms at all. But for others, AFib may cause:

- Exercise intolerance

- Fatigue

- Severe shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Palpitations

- Light-headiness

What causes atrial fibrillation?

Your heart is divided into four chambers: the two upper chambers called atria, and two lower chambers called ventricles. In order for blood to be pumped through your body, a group of specialized cardiac cells, the conduction system of the heart, sends electrical impulses to the atria that tells your heart to contract. Contractions of the heart send approximately five quarts of blood through your body every minute. In people with AFib, however, the impulses are sent chaotically. The atria quiver instead of beat; the blood isn't completely pumped out and may pool and potentially clot. AFib is a leading cause of stroke because of the anatomy of the left ventricle. For more information, read this article.

Are you at risk?

Your chances of developing AFib increase with age. AFib occurs more commonly in women than in men. According to the Framingham Heart Study, AFib is associated with a higher risk of death for women than for men. You are also at greater risk of developing AFib if you suffer from an overactive thyroid, high blood pressure, a prior heart attack, congestive heart failure, valve disease, or congenital disorders.

Diagnosis

AFib can sometimes be diagnosed with a stethoscope during an exam by a doctor or other health care provider and is confirmed or diagnosed with an electrocardiogram (EKG). There are several types of EKG’s. They are:

- Resting EKG – Electrical activity in the heart is monitored when a person is at rest.

- Exercise EKG – Activity is monitored when a person jogs on a treadmill or exercises on a stationary bike.

- 24-hour EKG (Holter Monitor) – A person wears a small, portable monitor that detects activity over the course of a day.

- Transtelephonic event monitoring – A person wears a monitor for a period of a few days to several weeks. When AF is felt, the person telephones a monitoring station or activates the monitor's memory function. This type of EKG is particularly useful in detecting AF that occurs only once every few days or weeks. Unfortunately this type of monitor does not record heart events while you are sleeping.

The image on this article is a typical EKG AFib recording showing the flutter of the atria followed by the ventricular contraction. In the larger image (click on the image of the article) you can see how this fluttering of the atria causes an abnormal spacing of the ventricular contractions which some patients feel in their chest.

PERSONAL NOTE: For more information on AFib and its surgical treatment, click here.

Thanks to Dr. Randall K. Wolf for the image and links

- Details

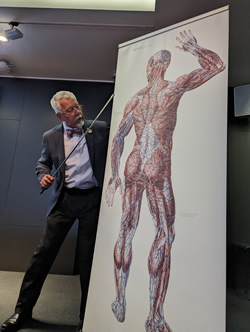

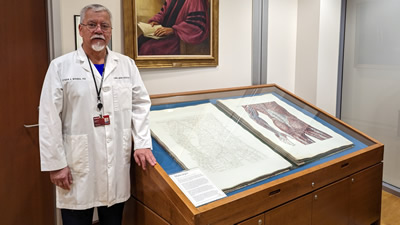

Dr. Miranda speaking at the

2023 Vesalius Triennial

I had the honor of being invited by the University of Antwerp in Belgium to speak at the 2023 Vesalius Triennial Meeting in the city of Antwerp. This scientific meeting was presented in conjunction with the 29th Congress of the Association Européenne des Illustrateurs Médicaux et Scientifiques - AEIMS (European Association of Medical and Scientific Illustrators). A three-day program that, alongside the scientific program, included poetry, art, music, sculpture, and painting. All of this celebrating the life and inspiration brought to arts and medical science by Andreas Vesalius Bruxellensis (1514-1564).

The scientific program included lectures by well-known Vesalius scholars, including Vivian Nutton, Robrecht Van Hee, Francis Van Glabbeek, Philip Van Kerrebroeck, Omer Steeno, Maurits Beisbrouck, Theodor Godeeris, Peter Bols, and many others. Personally, it was incredible to be invited to this event and share with these individuals.

One of the events of this meeting was an afternoon concert entitled “Vesalian landscapes in music, poetry, and photographs” by pianist Elke Robersscheuten, and my friend Theo Dirix, who read the poetry. This was accompanied by slides of Vesalian works, and images of the city of Brussels and the island of Zakynthos, Greece. One of the pieces performed by Elke Robersscheuten was “André Vésale”. Ths rare piece of piano sheet music is the topic for a separate article in this blog: An anatomical surprise from a French composer.

My presentation was entitled “Vesalius and Anatomical Megadrawings – A Personal Journey”. This is a topic that touched on my experience with larger (and very small) books and the sentence written by Andreas Vesalius in the two-page letter to Johannes Oporinus printed in the first part of Vesalius’ opus magnum “De Humani Corporis Fabrica, Libri Septem”. Referring to anatomical images, Vesalius states “quod tabulas quæe nunquam satis magna studiosis proponi poterunt”. Daniel H. Garrison in the latest publication of the Fabrica translates this as “illustrations which could never be large enough for students”.

The need for better resolution and the limitation of the printing technology (hand-carved woodblocks) at the time as well as the quality of the paper available forced the need for larger images. The Fabrica is a folio-size book and the images for the first time are labeled with letters, symbols, and characters with a detailed key as to their meaning.

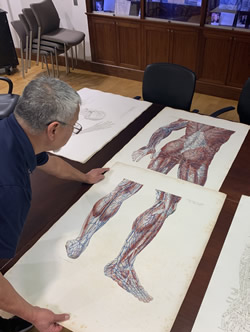

The research for this presentation took me to the largest anatomy book ever printed, the “Anatomiæ Universæ Icones” by Giovanni Paolo Mascagni (1755 – 1815), a double elephant folio size book measuring 40 by 30 inches with two sets of 44 plates. This book was printed in black and white and hand-colored by Antonio Serantoni (1780 – 1837), an Italian engraver and painter. The printing and coloring of this book took ten years between 1823 and 1832. An incredible book of which there are 16 known copies in the world, one of them at the University of Cincinnati.

Anatomiæ Universæ Icones by Paolo Mascagni at the University of Cincinnati

One of the most interesting aspects of this book, besides the large size of each image, is the fact that a 5.9 feet tall human can be constructed if three pages are cut and placed together. Of course, this cannot be done with these incredibly rare and expensive books; but digital technology allows us to scan and lightly correct the background to eliminate imperfections and damage caused by 200 years of use.

With the help of the University of Cincinnati authorities, Gino Pasi (archivist and curator of the Henry R. Winkler Center for the History of the Health Professions at UC), and Samantha Scheck (graphic designer) we were able to access the Mascagni book, measure the images, scan them, and them digitally process them. The result were two large images that I took to Antwerp, receiving incredible feedback from the attendees.

There is so much more to the life of Paolo Mascagni, before and after his death that include prison, family problems, greed, plagiarism, and a separate individual that is now known for his “dubious character”. I will write separate articles on these topics.

My presentation also touched on the large poster-like drawings (not books) that were used for anatomical teaching before the advent of the 35 mm slide projector and later PowerPoint with halogen light bulb projectors and today large LED monitors.

The anatomy amphitheater at the University of Chile Medical School

The anatomy amphitheater at the University of Chile Medical School

My alma mater, the University of Chile Medical School,has a museum and an old wooden amphitheater where I studied anatomy many years ago. As seen in the accompanying image, this auditorium has two incredibly large hand-drawn images that measure 13 feet in height and 5 feet in width.They are copies of the "Traité complet de l’anatomie de l’homme"

by J.M. Bourgery (1831-1854) made by the Chilean painter Juan Frutos M.

The anatomy amphitheater has been deemed National Heritage by the government of Chile and it will be preserved as is. Below the seating area there was a room closed for decades. In it there were found 500 large scrolls that are worthy of research and preservation. These were hand-painted by 47 different authors, some medical students and artists. From the artistic point of view, research needs to be done on the media used as well as the method of painting.

In the time I was a student, these scroll megadrawings were not in use as an old electric arc projector with glass slides were used in its place.

The information on these drawings can be found in the book “Instituto de Anatomía: Un Recorrido Visual” by Prof. Julio Cárdenas V. My personal thanks to Dr. Cárdenas for facilitating digital images of his book for my presentation.

The meeting included an artistic midday soiree entitled “Vesalian Landscapes in music, poetry and photographs” by pianist Elke Robersscheuten and Vesalius expert and taphophile Theo Dirix.

This afternoon concert was followed by scientific poster presentations, an exhibit of anatomical art, and presentation of art and medical books, including “The King’s Anatomist” by my friend Ron Blumenfeld.

As the closure of the meeting, the attendees were invited to a guided tour of the Plantin-Moretus Museum, an institution that preserves the rich history of printing in the 16th century. This tour also deserves a separate article with pictures.

Francis Van Glabbeek, an orthopedic surgeon at the University of Antwerp invited my good friend Dr. Randall Wolf and me to visit his personal rare book collection, which includes not only a 1543 and a 1555 Fabrica, but rarities like books by Bidloo, Cowper, Hyeronimus Fabricio de Aquapendente, and a copy of the “Epistola rationem modumque propinandi radicis Chynae decocti” which was one of the books mentioned in my presentation. A meeting that only collectors of rare books could understand! Later in the day Dr. Van Glabbeek took us to Verrebroek, the city where another famous Flemish anatomist was born: Philippo Verheyen.

I cannot end this article without reiterating my thanks for the invitation to the organizing committee of this fantastic meeting:

Ann Van de Velde

President AEIMS, University of Antwerp

Pascale Pollier-Green

Past-president AEIMS, University of Antwerp

Francis Van Glabbeek

President BIOMAB, University of Antwerp

Bob Van Hee

Emeritus Professor of Surgery and Medical History

Director of the Lambotte Museum for the History of Health Care, University of Antwerp

Marc de Roeck

University of Antwerp

PERSONAL NOTE: I was invited to deliver a variation of this presentation in November 2023, at the LVIII Chilean Anatomical Society Meeting in Santiago, Chile.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

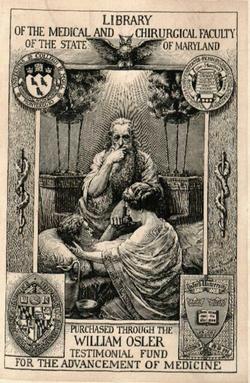

For centuries, book owners and collectors have used bookplates to identify their books and their collections, a tradition that seems to be falling in disuse. Not me, I have one that you can see here.

Bookplates (also known as Ex-Libris) can be a tantalizing study, and finding an interesting one is part of what makes an old book a journey of discovery. Every detail in an old book is important. Who owned it? What is their story? Did they leave personal notes within the pages of the books? I have found prescriptions, personal notes, medical shopping lists, and in some cases corrections to the book itself! One of the most interesting cases of this is Vesalius' Annotated Fabrica!

Bookplates are very personal. In many cases, they depict the coat of arms of the owner’s family, sometimes a motto that drove the book’s owner, the book owner's hobbies, and in some cases a humorous jab at something.

While researching my series of articles on Dr. Ephraim McDowell, I ordered the book “EPHRAIM MCDOWELL, FATHER OF OVARIOTOMY AND FOUNDER OF ABDOMINAL SURGERY. With an Appendix on JANE TODD CRAWFORD”. By AUGUST SCHACHNER, M.D. Cloth, 8vo.A p. 33I. Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott CO., I921. A great book, I finished reading it overnight!. Dr. McDowell has also been featured in this blog in the series "A Moment in History"

What interested me was the bookplate on the book frontis, a picture of which I placed in this article. It is from the Library of the Medical and Chirurgical faculty of the State of Maryland, and has a legend that states "Purchased through the William Osler Testimonial fund for the advancement of Medicine”. It depicts a physician (probably Hippocrates) taking the pulse of a patient.

Further research indicated that this bookplate was created to honor Sir William Osler by the Maryland State Medical Society and that Dr. Osler’s books never had personal bookplates. MedChi (Maryland State Medical Society) commissioned this plate that depicts the four seals of the universities with which Osler was affiliated: McGill in Montreal, University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Johns Hopkins in Baltimore and Oxford in England. The images are flanked by two rods of Asclepius.This Ex-Libris was designed and drawn by Max Brödel (1870 – 1941) a famous medical illustrator who worked at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore and illustrated for Harvey Cushing, William Halsted, Howard Kelly, and other notable clinicians. Brödel was a personal friend of Osler. The bookplate was such a hit that doctors from all over the country requested copies of it, which the librarian at the time Ms. Marcia Crocker Noyes, sent but with the request of receiving the requestor’s own bookplate. You can see all of them in the attached links in the "Sources" section. Interestingly, Ms. Marcia Crocker Noyes has been suspected of still haunting the library where she worked!!

An old book is important not only because of its content, but also because of its provenance. You know where you are going to start reading it, but you never know where are you going to end in researching it. Should you want to have your own bookplate, you can order them from BookPlateInk. On a personal note, develop your own bookplate. It's your legacy. If you want to see my Ex-Libris, it is in my library catalog page. Dr. Miranda.

Sources:

1. Ex Libris: The Bookplate Collection, Part I MedChi

2. Happy Birthday, Sir William! MedChi

3. The bookplate that never was McGill University (PDF)

4. The Osler Library of the History of Medicine: McGill's Medical Memory. Lyons C Mcgill J Med. 2011 Jun; 13(1): 90.

5. The MedChi Collection of Bookplates

6. Max Brödel & MedChi

- Details

UPDATED: This article was originally titled "[friggatriskaidekaphobia], a word that means "fear of Friday the thirteenth".

It is based on the term [triskaidekaphobia] which means "fear of the number thirteen". Although in modern Greek the number thirteen is pronounced [dekatria] (δεκατρία), the term triskaideka means "three and ten" in older Greek. Add the Greek suffix [φοβία] [phobia] meaning "fear" and you have the word triskaidekaphobia. An alternate spelling is triskadekaphobia

The term [Frigga] refers to a Norse goddess after whom the name for the day Friday originates. Frigga is the wife of Odin and the mother (or stepmother, depending on who interprets old traditions) of Thor.

Reading the book "Complications: Notes from the Life of a Young Surgeon" by Atul Awande. MD (one of the books in my library) I came across a synonym for this concept, the word "paraskevidekatriaphobia" also written as "paraskevideikatriaphobia". The author does not explain the origin or etymology of the term. What he does say is that in the United States, on Friday the 13th, people "perform rituals before leaving the house, call in sick to work, or postpone flights or major purchases, causing businesses to lose $750 million annually". Keep in mind that this book was written in 2002. A simple calculation at https://www.inflationtool.com/ shows that by 2022, this corresponds to 1.2 billion dollars!

The origin of the superstition that Friday the 13th is a bad day started on Friday the 13th, 1307. On this date all the Knights Templar were rounded, arrested, accused, tortured, and executed. It is indeed a bad day, but only if you are a member of the Knights Templar!