Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 875 guests online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

The King's Anatomist - Book Cover

Click on the image for a larger version

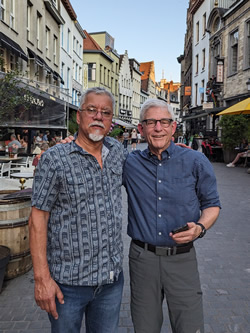

[UPDATED 11/30/2023] “In 1565 Brussels, the reclusive mathematician Jan van den Bossche receives shattering news that his lifelong friend, the renowned and controversial anatomist Andreas Vesalius, has died on the Greek island of Zante (today’s Zakynthos) returning from a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Jan decides to journey to his friend’s grave to offer his last goodbye…” Thus begins the saga and the book the “King’s Anatomist”.

In June 2022 during the annual American Association of Clinical Anatomists (AACA) meeting in Fort Worth, TX, I was lucky to bid and win this, one of the latest books on Andreas Vesalius. This book, written by Ron Blumenfeld, MD. proved to be not only a great read, but also an quite historically accurate story. Let me explain this statement.

The book belongs to the genre of Historical Fiction, where the author does detailed research on a topic and then writes on accurate background but adds fictional characters and situations. Sometimes, as in this book, it follows a mystery that slowly unravels leading to shocking situations. To be fair, the author does explain what is not necessarily quite historically accurate, so as to leave no doubt about what is real or not.

The book is enthralling, the plot well developed, and the description of the academic environment, the details of the scenery for the travelers, the pettiness of war, etc., is not only interesting, but also portrays the times during the life of Andreas Vesalius in such a way that I felt transported there. It was very difficult to put the book down until I finished it.

The author does a great job getting us a little bit closer to who was Andreas Vesalius, the child at school, the youngster, the anatomist, the friend, the father, and the husband.

I should probably stop here and let you decide on the book for yourself without giving too much away. I strongly recommend this book and hope that you will enjoy it as much as I did. You can visit Ron’s website here to buy his book.

Ron and I both attended the 2014 “Vesalius Continuum” meeting in the Greek island of Zakynthos. This meeting celebrated the 500th anniversary of the birth of Andreas Vesalius. Part of the book he wrote is based on the discussions and presentations at this meeting.

Following are some excerpts of Ron’s bio and website in his own words:

“I’m a native New Yorker, pediatrician and health care executive who reunited with his inner writer in retirement. I surrendered the pleasure of writing columns on various topics for my local newspaper in Connecticut to focus on my debut novel, The King’s Anatomist”

“There always was a writer cooped up inside me, but he got loose only after I retired. I had permitted him to show up only in school classes, health and business writing, and newspaper columns, but I realize now that I kept him on a short leash because I was afraid of him – afraid of his disruptive potential and afraid of what he would look like to the world. But at this point in my life, I got past those excuses and let him out to see what he could do.

"The King’s Anatomist, it turned out, was an ideal writing project, anchored in facts, but with ample room for creativity. Thank you, Andreas Vesalius, for being such an interesting guy.”

UPDATE: I was glad to see Ron Blumenfeld again when he attended the 2023 Vesalius Triennial Meeting in the city of Antwerp, Belgium where I had been invited to participate. We had a great time in the conference, walking around the city, and at local restaurants! Also, thank you, Ron, for signing and dedicating my personal copy of your book. It has a nice place in my library. Dr. Miranda.

Should you want to look for more information on Andreas Vesalius in this website click here.

- Details

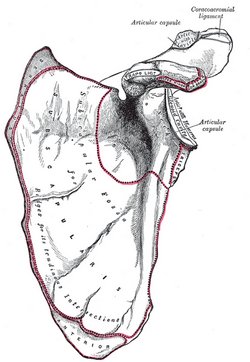

Anterior view of the left scapula

UPDATED: The scapula, known vernacularly as the "shoulder blade", is a flat, triangular bone that forms the posterior portion of the shoulder girdle. It is described with two surfaces, three borders, and three angles. The scapula attaches to the clavicle by way of the acromioclavicular joint and ligaments. Seventeen muscles attach to the scapula and are discussed in a different article.

This bone actually has two names depending on the language used. In English we use the word [scapula] which has a Latin origin, while in some Latin-based languages the word [omóplato] (Spanish, in this case) has a Greek origin!

[Scapula] originates from the Latin [scapula] (scapula), meaning “shoulder”, also “the back”. The later derivation into “shoulder blade” in English has no known history, except perhaps for the primitive use of animal scapulae as a blade or a spatula in daily chores.

In Greek the term [ωμοπλάτη] (omopláti) was used to name the scapula. The origin of the word was the combination of the terms [ώμος] (ómos) meaning “shoulder”, and the word [πλάτη] (pláti) meaning “back”. One of the seventeen muscles that attach to the [scapula] is the [omohyoid], where the root term [-omo-] indicates its relation to the scapula.

It was Andreas Vesalius who popularized the name [scapula] selecting it from the many names this bone had at the time (1543), and is today the the accepted “Nomina Anatomica” term.

There is still discrepancy on the name of the bone in other languages.

• English: scapula

• Spanish: omóplato, also escápula

• Italian: scapula

• French: omoplate

• Romanian: omoplat

• Portuguese: escápula

In German, they used the word [schulterblatt] which means "shoulder blade".

The anatomical description of this bone continues in this article

Sources:

1. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

2. "Gray's Anatomy" 38th British Ed. Churchill Livingstone 1995

3. “The Origin of Medical Terms” Skinner HA 1970 Hafner Publishing Co.

4. "Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology (FCAT)" Thieme, 1998

Image in Public Domain, by Henry Vandyke Carter - Gray's Anatomy

Note: The links to Google Translate include an icon that will allow you to hear the Greek or Latin pronunciation of the word.

- Details

The Anatomical Basis of Medical Practice - Book Cover

Click on the image for a larger version

The title of this article paraphrases the title of a paper authored by Edward Halperin, MD, MA., and published in “Academic Medicine,” the Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges in February 2009. More information in the "Sources" section of this article. I have also used other sources to complete this "strange tale."

"The Anatomical Basis of Medical Practice" was published in 1971 by Williams & Wilkins. A large and heavy book, it is one of the many anatomy books written for medical students. This one however, stirred a controversy because of the "tongue-in-cheek" writing style of the authors and mostly because of the photographs of female nude models in seductive poses pretending to depict surface anatomy. The pictures were taken by a famous photographer, Peter Gowland.

Initial reviews were positive, as stated in the British Journal of Surgery, where the book is praised saying: "one only wishes that such a book was available when one was a student in the dissecting room."

Other reviews were more negative, as Dr. Edward A. Edwards in 1972 states: "...I feel compelled to say that the numerous photographs of comely young women, while enticing, no not well demonstrate the muscles and bony points the legends suggest as their purpose." He also says: "The book is marred by a waggishness expressed in facetiousness and in long digressions...."

Soon negative reactions to the book took place, many of them from anatomy professors who saw the illustrations as "out of place" and "not needed". Interestingly only a small percentage of the total images were of the "Playboy" style, while the rest of the images, photographs and sketches are of high educational quality.

Estelle R. Ramey, Emeritus Professor of Physiology and Biophysics at the Georgetown University School of Medicine, in a letter to the Association of Women in Science stated “In effect, the entire book is a calculated insult to women and men alike. It demeans the whole profession of medicine and is openly contemptuous of middle-aged women whose breasts are not so round and may even be rotting with cancer.” The AWIS as a whole threatened to boycott Williams and Wilkins Publishing, and as a result, the book was pulled off the market.

The story gets more interesting. Because of public pressure, angry letters to the publisher, and boycotts, the publisher agreed to stop all promotion, marketing, and sales of the book. Many assumed that they pulled the book off the market when, apparently because of low sales, they just let the initial run sell out by December 1972 and never republished it.

I do agree that the book transgresses the lines of decorum and respect for women that exist today. At the time of its publication the feminine movement was starting, and I think the authors tried (and failed) to have a humorous approach to what is at best, a difficult subject.

The book itself is a great book on anatomy and superficial anatomy, notwithstanding the images and comments. Since it was published and because of its scarcity, it has become a rare book, and as Dr. Halperin states “a minor collector’s item.” When published, this book sold for US$23.00. In 2009, at the time Dr. Halperin published his paper, the book was valued between US$ 89.00 and US$ 300.00; today (2025,) the book is valued between US$ 575.00 and US$1,000.00 in Abebooks.com.

"The Anatomical Basis of Medical Practice" by Becker, R; Frederick; Wilson, James W; and Gehweiler, John, A. is one of the many books in my library and it has become known as “the green book” among my colleagues because of its bright green cloth hardcover. The image in this article is from the book in my library.

Sources:

1. “The Pornographic Anatomy Book? The Curious Tale of The Anatomical Basis of Medical Practice" Halperin, E. Academic Medicine: February 2009 - Volume 84 - Issue 2 - p 278-283

2. "The anatomical basis of medical practice." By R. Frederick Becker, Ph.D., James W. Wilson, Ph.D., M.D., and John A. Gehweiler, M.D. 11 × 8¼ in. Pp. 907 + xv. Illustrated. 1971. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

3: "Five centuries of gender bias in anatomy" Elisabeth Brander — December 9, 2021

4. " The Anatomical Basis of Medical Practice (NSFW)" September 10th, 2012

5. "The Anatomical Basis of Medical Practice" by Becker, R; Frederick; Wilson, James W; and Gehweiler, John, A. 1971. The Williams & Wilkins Company

6. "The Anatomical Basis of Medical Practice" Book Review by Edwards, E. Ach. Surg. 1972

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Celsus and Title Page De Medicina Libri Octo”

Click on the image for a larger version

Aulus Cornelius Celsus (25 BC - 45 AD) was Roman, probably born in the south of France. A controversial character, many dispute that he was even a physician or that he actually did what is mentioned in his opus magnum “De Medicina Libri Octo.” According to some, he was what today would be considered a compiler and editor of larger books where each chapter is written by a different author. Others present Celsus as a learned scholar of noble origin, a famous physician, either way, he influenced Medicine and Surgery for centuries. Some of his canons and medical terms he coined are in use today. such as omentum, cancer, vertebra, scalpel, etc.

He is the first to describe the four pillars of inflammation: dolor (pain), rubor (redness), calor (fever), and tumor (swelling) , and in passing criticizes Erasistratus on being wrong about inflammation. In his book he states “Notæ vero inflammationis sunt quatuor, rubor, et tumor, cum calore et dolore. Quo magis erravit Erasistratus, qui febre nullam sine hac esse dixir.” Translates as: “Note that there are four signs of inflammation: redness and swelling, with heat and pain. So much was Erasistratus mistaken, when he declared there was no fever without it.” Celsus popularized the use of the term “cancer”. although it was first used by Galen of Pergamon.

Not much is known about his life or work. Quintilian mentions a work of Celsus on rhetoric, but that work is lost. Quintilian, who apparently was not a fan of Celsus, writes: “…when even Cornelius Celsus, a man of a moderate share of genius, has not only composed treatises on all these arts, but has also left precepts of the military art, agriculture, and medicine.” His quote is what leads Alexander of Padua to state that his book “De Medicina, Libri Octo” is but a small part of a larger treatise that was called “The Arts.” Celsus is known by his book “De Medicina, Libri Octo,” (On Medicine, eight books). This book is sometimes presented as “De Re Medicina, Libri Octo.” Apparently, this book was part of a larger work by Celsus that has disappeared from History. This medical book was handwritten and was lost to history until one copy was discovered in the Vatican Library and released for copying as manuscripts. Of interest is the fact that the book found was titled "Aulii Cornelii Celsi liber sextus. idemque medicinæ primus," making it understood that these were six books, not eight! This was one of the first medical books to be printed upon the invention of the printing press by Gutenberg.

The first book begins with the principles for the preservation of health; the second is dedicated to the symptoms of diseases; the third is describes treatment of diseases which affect the whole organism and the fourth is focused on the diseases where the cause is found only in certain parts of the body, such as in head, lungs etc. The fifth book is dedicated to pharmacology. The sixth, seventh, and the eighth book deal with surgery, wounds, and fractures.

His book describes the importance of cleanliness of a wound and the use of topical treatment that today would be considered antiseptics. His contributions to surgery are many including anatomy of the eye, the description of ophthalmic diseases, methods of preventive treatment and surgery including eyelid surgery. He is probably the first to describe cataract surgery.

The eighth book, almost entirely dedicated to dislocations and fractures, provides an extensive description of head injuries such as extradural hematomas, lesions distant from the impact point, and intracranial damage in cases with no overlying fractures. He also provided the first description of brain swelling exceeding the level of the skull, described several surgical indications and craniotomy techniques, recommended treatment for depressed fractures (which had been previously considered untreatable), and detailed the surgical instruments employed.

De Medicina was among the first medical books to be printed (Florence, 1478), and more than 50 editions have appeared; it was required reading in most medical schools to the present century. It is the principal historical authority for the doctrinal medical teachings of Roman antiquity. The surgical section, which even Joseph Lister studied in the 19th century, is perhaps the best part of the treatise.

W. G. Spencer, the most recent translator of his works, supports an older, minority view that the details of medical procedure, the experienced judgment shown in the selection of treatment, and the frequent use of the first person reveal an author with an intimate acquaintance of clinical medicine who must have been himself a practitioner of the medical arts.

Because of this book and the clarity of the disease descriptions and treatments both pharmacological and surgical. Celsus has been lauded as one of the Fathers of Medicine and Surgery. His influence has stood the test of time and was read well into the 1800’s.

Personal note: This article was motivated by the recent acquisition of a 1713 copy of De Medicina, that is now part of my library. The book belonged to Dr. Harry Kaufmann Hines, a renown radiologist who lived and worked in Cincinnati, OH. The book was a gift to him from his sister-in-law Erma Wright Tateman neé Sharkey in August 1961. Dr. Miranda

Sources:

1. “The Contribution of Aulus Cornelius Celsus (25 B.C.–50 A.D.) to Eyelid Surgery” Davide Lazzeri, Tommaso Agostini, Michele Figus, Marco Nardi, Giuseppe Spinelli, Marcello Pantaloni & Stefano Lazzeri (2012), Orbit, 31:3, 162-167

2. “Aulus Cornelius Celsus and the Head Injuries” GiuseppeTalamonti Giuseppe D'Aliberti, MarcoCenzato World Neurosurgery Volume 133, January 2020, Pages 127-134

3. “A. Cornelius Celsus of medicine. In eight books.” Translated, with notes critical and explanatory, by James Greive, M.D. 1756

For anyone interested in reading an online copy of this book, you can find it here. For the translation by Greive click here.

- Details

UPDATED: After a long hiatus, I am happy to report that this website has been updated to a newer version of Joomla!, and still hosted by GoDaddy. The "look" of the website has not changed, but the software is faster and with a higher level of security. This work was done by my good friend from Greece, Christopher Mavros, who is an expert at designing web templates, web sites, and Joomla! extensions. This also meant that my library catalog was left unfinished for a long time and this required lots of additional work.

First, the library needed new and updated bookplates, which were printed by BookplateInk, a USA based company that I strongly recommend. In case anyone wonders, the famous anatomists that are depicted in the bookplate are Harvey, Vesalius, Spigelius, and Albinus. Second, I needed software that could create the code to publish the titles of the library online. This work was done by my daughter Evelyn, to whom I am deeply grateful.

Recataloging the library is an ongoing effort. This will also require repairing and rebinding some of the older and damaged books. Due to this, during the next weeks and months this listing will change, but for a bibliophile this is not work, but pleasure.

As many of you know I am a collector of old and antique medical and anatomy books and I also have several copies of some of these books in different languages.

The oldest book in the library dates from 1696 and is "Opera Chirurgica Anotomica Conformata al Moto Circolare Del Sangue, & Altre Inuenziono De'piu Moderni. Aggivuntovi Un Trattato Della Peste" by Paolo Barbette. I recently acquired the 1713 book by Aulus Cornelius Celsus "De Medicina, Libri Octo".

Another book I am very proud of is not old, but still a rare book. It is "The Fabric of the Human Body, An Annotated Translation of the 1543 and 1555 Editions of “De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem", by Drs. Garrison and Hast This monumental translation work took twenty years and only 948 copies of this book were published in 2014. Completely sold out, it is today a rare book!

There are many other books that are important to me, either by its rarity (for those who know.... "The Green Book") or its controversy, as are the books by Pernkopf and Stefano Mancini.

You are welcome to peruse my library catalog, but be forewarned; I am not selling any of my books. Should you want to find a copy, you can use Abebooks.com as a great source for old and new books.

- Details

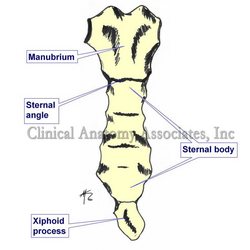

Click on the image for a larger version.

UPDATED: The term [xiphoid] is Greek in origin [ξίφος] and points to the similarity [-oid] of the sternum to a short straight sword used by the Greek. The term xiphoid refers to the lower cartilaginous inferior tip of the sternum. It presents with anatomical variations that include a central opening, or large processes that look like a disc, or even a bifid xiphoid process.

It has been named the xiphisternum, the metasternum, and the ensiform process. It is the last cartilage to ossify in the human, and it is used as a landmark for laparoscopic surgery. i.e. a subxiphoid port is a location for a laparoscopic port in the abdomen.

As a side note, another term used for [sternum] is the Latin word [gladius], referring to the short Roman straight sword of the gladiators. This term is no longer in use, but if it were, the xiphoid appendix would be the tip of the sword.

Think about this: why is a certain plant called a "gladiolus"?

Image property of:CAA.Inc.. Artist:David M. Klein