Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 835 guests online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Andreas Vesalius Bruxellensis (1514- 1564). A Flemish anatomist and surgeon, Andreas Vesalius was born on December 31, 1514 in Brussels, Belgium. He is considered to be the father of the science of Anatomy. Up until his studies and publications human anatomy studies consisted only on the confirmation of the old doctrines of Galen of Pergamon (129AD - 200AD). Anatomy professors would read to the students from Galen's work and a demonstrator would point in a body to the area being described, if a body was used at all. The reasoning was that there was no need to dissect since all that was needed to know was already written in Galen's books. Vesalius, Fallopius, and others started the change by describing what they actually saw in a dissection as opposed to what was supposed to be there.

Vesalius had a notorious career, both as an anatomist and as a surgeon. His revolutionary book "De Humani Corporis Fabrica: Libri Septem" was published in May 26, 1543. One of the most famous anatomical images is his plate 22 of the book, called sometimes "The Hamlet". You can see this image if you hover over Vesalius' only known portrait which accompanies this article. Sir William Osler said of this book "... it is the greatest book ever printed, from which modern medicine dates"

After the original 1543 printing, the Fabrica was reprinted in 1555. It was re-reprinted and translated in many languages, although many of these printings were low-quality copies with no respect for copyright or authorship.

The story of the wood blocks with the carved images used for the original printing extends into the 20th century. In 1934 these original wood blocks were used to print 617 copies of the book "Iconaes Anatomica". This book is rare and no more can be printed because, sadly, during a 1943 WWII bombing raid over Munich all the wood blocks were burnt.

One interesting aspect of the book was the landscape panorama in some of his most famous woodcuts which was only "discovered" until 1903.

Vesalius was controversial in life and he still is in death. We know that he died on his way back from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, but how he died, and exactly where he died is lost in controversy. We do know he was alive when he set foot on the port of Zakynthos in the island of the same name in Greece. He is said to have suddenly collapsed and die at the gates of the city, presumably as a consequence of scurvy. Records show that he was interred in the cemetery of the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie, but the city and the church were destroyed by an earthquake and Vesalius' grave lost to history. Modern researchers are looking into finding the lost grave and have identified the location of the cemetery. This story has not ended yet.

For a detailed biography of Andreas Vesalius CLICK HERE.

Personal note: To commemorate Andrea Vesalius' 500th birthday in 2014, there were many scientific meetings throughout the world, one of them was the "Vesalius Continuum" anatomical meeting on the island of Zakynthos, Greece on September 4-8, 2014. This is the island where Vesalius died in 1564. I had the opportunity to attend and there are several articles in this website on the presence of Andreas Vesalius on Zakynthos island. During 2015 I also attended a symposium on "Vesalius and the Invention of the Modern Body" at the St. Louis University. At this symposium I had the honor of meeting of Drs. Garrison and Hast, authors of the "New Fabrica". For other articles on Andreas Vesalius, click here. Dr. Miranda

- Details

- Hits: 85306

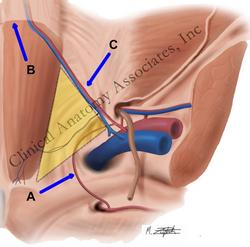

UPDATED: The "triangle of doom" is a name given to a roughly triangular area in the posterior aspect of the anterior wall of the lower abdominopelvic region. It is used by surgeons repairing an inguinofemoral hernia with a mesh and they want to avoid large vascular structures, namely the external iliac artery and vein. The "triangle of doom" will be highlighted when you hover your cursor over the image.

The so-called "triangle of doom" is a misnomer perpetuated by the first laparoscopic surgeons who observed the anatomy of the inguinofemoral region from the posterior aspect. It is neither a triangle (as it only has two boundaries), nor is it an eponym (no such person existed - that is why uppercase should not be used). It does indicate an area where it is extremely dangerous to place staples or sutures during laparoscopic hernia surgery.

The "triangle of doom" is an inverted "V" shaped area with its apex at the internal (deep) inguinal ring. The "triangle of doom" is bound laterally by the gonadal vessels, and medially by the vas deferens in the male, or the round ligament of the uterus in the female. Within the boundaries of this area you can find the external iliac artery and vein.

It should be pointed out that although the "triangle of doom" landmark does protect the surgeon from damaging the external iliac vessels, a portion of these vessels lie outside of this area. In fact, there are several other areas of concern for neurovascular damage when performing a laparoscopic herniorrhaphy.

Hover over the image in this article, and the triangle of doom will appear. Clicking on the image will show a larger image of the posteroinferior abdominal region. The image also depicts other structures of anatomical importance for laparoscopic herniorrhaphy:

• Arcuate line (b)

• Hesselbach's triangle (in yellow)

• Aberrant obturator artery (Corona Mortis) (a)

• Inferior (deep) epigastric artery (c)

Image property of: CAA.Inc. . Artist: M. Zuptich.

Clinical anatomy of the inguinofemoral hernias, as well as abdominal and perineal hernias are some of the lecture topics developed and delivered to the medical devices industry by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. For more information Contact Us.

- Details

- Written by: Pascale Pollier-Green

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

If you arrived directly to this article, the first article in this three-page series can be read HERE

Bryan Green reading his poem in Theo Dirix's

book “ In Search of Andreas Vesalius”

Click on the image for a larger version

I would like to shine a light on my husband poet /sculptor Bryan Green , who wrote a poem on Vesalius that is published in Theo’s book; “In Search of Andreas Vesalius: The Quest for the Lost Grave” and gave a performance at the Fabrica Vitae exhibition opening.. Bryan has constantly worked behind the scenes editing many letters, articles, books, and leaflets, I couldn’t have done it all without his help and advice. He also made the long lorry journey to Zakynthos from Belgium with me and our friend James Gatehouse to deliver the monument.

Vesalius Continuum also marked the start of our touring exhibition “Fabrica Vitae” curated by Eleanor Crook, my sister Chantal Pollier, and myself. The exhibition toured all over Europe and the US with the help and support of Theo Dirix and Belgian Embassies world wide .

The conference and accompanying events could not have happened without financial funds and I hereby would like to thank all our sponsors: Professor Peter Abrahams with his infectious energy and professor Robert Jordan; St Georges University of Grenada, Ruth Richardson and Brian Hurwitz and Mark Gardiner for getting funding from the Wellcome trust, Marie Dauenheimer and the Vesalius Trust, BIOMAB, Ann van the Velde and The University of Antwerp, The AEIMS and MAA, William Nagels, warmly thank the local authorities and the mayor of Zakynthos, ARSIC, Theo Dirix, and Stephen Joffe, and a special thank you also Stephen for writing a beautiful foreword for our book In the Shadow of Vesalius.

You can imagine after such an exciting and wonderful adventure, which took quite a few years to organize, and a quite a few years to reminisce over, we decided we wanted to keep the momentum going and thus the Vesalius triennial was born.

In 2017 BIOMAB, in collaboration with Vesaliana, organized the first triennial in Zakynthos ‘Uniting Medicine with Poetry, History and Culture’

It seems like another world in which we made our plans for the 2nd edition of the Vesalius Triennial Congress, 4 months before the COVID-19 pandemic lock down. From the vain belief that COVID-19 would not hit most countries, to hopes that everything would have blown over by 13th November 2020 (the day when the next Vesalius Triennial Congress would take place in Antwerp) to realizing that we were going to have to take action, the scientific committee has transformed from one in which everyone knew their time-tried and perfected role, to one requiring invention in uncharted territory.

Professors Vivian Nutton and Omer Steeno

looking at a first edition of the Fabrica

Canceling the 2nd Vesalius Triennial was not a welcome prospect , since facilitating human communication is the corner stone of a scientific community. So we set sail for the vast virtual-reality realm. To discover just how far we could delve into virtual communication with a dedicated but small organising committee, was an eventful, insightful voyage. Sadly after long and careful consideration and several online meetings we finally decided to postpone all international congress keynote lectures and educational sessions until 2023.

However we would like to invite all the friends of Vesalius for a virtual book launch on Nov 13th we will soon post the event details on how to register for this event on social media, and on Vesalius continuum website

The book "In the shadow of Vesalius" can be ordered here: http://garant.be/shadow-of-vesalius/

Finally I would like to thank everyone who has been part of this adventure, special thank you to Professor Dr. Efrain Miranda ( Clinical Anatomy) for his continuous support, EBSA, Prof. Stefanos Geroulos, Vasia Hatzi (MEDinART), Pavlos Plessas, Nicos Varvianis, Maria Sidirokastriti-Kontoni & Fr. Panagiotis Kapodistrias, the many wonderful speakers, the local organisers, our Keynote speaker Professor Martin Kemp for his wonderful contribution, Eleni Andrianaki; ibis el greco , the wonderful delegates, the artists of the Fabrica Vitae exhibition, the museum and universities where we took our exhibition, a special thank you to Juris Salaks and Ieva Lebiete for hosting our exhibition at the Stradins museum and for all the help and support, Apostolis Sarris, Nikos Papadopoulos, Sylviane Déderix, Jan Driessen, Theo Dirix, Chr. Merkouri.and to the all the friends of Vesalius who like to keep his spirit alive.

Pascale Pollier-Green

Oct 2020

Personal note: I would like to thank Pascale Pollier-Green for authoring this series of articles and wish Professor Robrecht Van Hee the best success publishing this new book on the history and influence of Andreas Vesalius on anatomy, medicine, science, and the Arts. Dr. Miranda.

- Details

- Written by: Pascale Pollier-Green

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

If you arrived directly to this article, the first article in this three-page series can be read HERE

Sculpting the monument in Richard Neave’s studio

One of the most important conferences that BIOMAB initiated and co-organized was without doubt “Vesalius Continuum” which took place in 2014 on the island of Zakynthos . This joint AEIMS conference was organized in collaboration with Dr Mark Gardiner and the then Consul at the Belgian Embassy in Greece - Theo Dirix, and brought together many prominent scholars and Vesalius experts who presented papers on the life, work and death of Vesalius, and the influence of the Fabrica on modern anatomy, and on medical art and contemporary art (pdf file).

Without the organizing skills and drive and energy of Dr. Mark Gardiner and the countless meetings and emails with Theo Dirix, the conference Vesalius Continuum would not have been the huge world class event it became.

In 2013 Dr. Mark Gardiner and I first introduced ourselves to Professor Vivian Nutton who was giving a lecture at Warwick University about the incredible find of a hand written (by Vesalius himself !) edited version of the Fabrica’s second edition, which would have become the third edition, …had Vesalius not met his untimely death. Mark and I were blown away by this wonderfully exciting lecture and we asked Professor Nutton to be a speaker at our conference in 2014, which he accepted gladly. He was invited again in 2017 for the triennial and has now especially for this publication written an exciting account of Vesalius in England, 1544 to 1547.

Vesalius’s 500 th anniversary celebrations did not end with the organization of the conference, but became a collection of several events.

My colleague and dear friend forensic medical artist Richard Neave and I sculpted a bronze monument to commemorate Vesalius’s death on the Island of Zakynthos on 15th Oct 1564. This monument might never have been erected if it were not for the wonderful idea of Antwerp GP and president of Vesaliana Dr Marc de Roeck together with William Nagels, who devised a way of self-funding this large undertaking. We had countless meetings discussing the monument and agreed with Dr. de Roeck that by making a bronze facial reconstruction portrait (made by Richard Neave and myself) and selling 12 copies we would gather enough money together to make the monument, pay to have it cast in Bronze and drive the sculpture from Belgium to Zakynthos ready to have its grand inauguration at the start of the conference. This was all achieved successfully and the sculpture now stands on the Island of Zakynthos’s Vesalius square, facing the Ionian sea.

Dr. Marc De Roeck and Pascale Pollier

sailing to Zakynthos

In 2009 I had completed a facial reconstruction course at the academy of fine arts in Maastricht , the Netherlands, and as Vesalius had always been my big inspiration and the reason why I chose to become a medical artist, it was my dream to make a facial reconstruction of Vesalius. The dream soon turned into a passion, and the passion into an obsession to go in search of the grave of Vesalius and find his skull.

Ann suggested to Marc we sailed to Zakynthos with the MYC-Medical Yachting Club to start the quest for the grave. I will never forget the day that Marc gave me the ships wheel as we got closer to the island and I sailed into the harbor of Zakynthos! An amazing feeling!

After our first visit to “what we thought then was the grave site“ at Laganas, I wrote a letter to the Belgian embassy in Greece, asking for help with our quest, a year later when Theo Dirix took office as Consul he wrote back to me, my letter had ignited a flame in the heart of taphophile Theo Dirix.

Soon the quest became an official scientific research collaborative project between the Belgian School of Athens (Jan Driessen, Apostolis Sarris, Sylviane Déderix) and the Greek authorities, together with the invaluable research of Omer Steeno, Maurits Biesbrouk and Theodoor Godeeris, who all share their latest findings in this book. With this wonderful collaborative effort, even though we have not yet found the actual grave, we can truly claim that we have made some history.

Theo Dirix wrote 2 books on the quest of the grave and now will reveal some new insights with his article in the book “In the Shadow of Vesalius”.

This article continues HERE

- Details

- Written by: Pascale Pollier-Green

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

The following article was written by my good friend Pascale Pollier-Green and it recounts the long road that has taken her and other Vesaliana followers all over the world, and has resulted in the publication of the book "In the Shadow of Vesalius". Dr. Miranda

The concept behind the book “In the shadow of Vesalius” is probably best described by the opening address of the editor and one of the authors, Professor Robrecht Van Hee. Following here are a few excerpts from his transcript:

Pascale Pollier-Green, author of this article

“The quincentenary of Vesalius’s birthday in 2014 has been characterized by a flow of colloquia and publications on the Flemish anatomist, often presenting new insights concerning his life and death, as well as concerning his works and iconography.

This revival of interest has subsisted and induced new symposia and initiatives, resulting in new congress proceedings and publications, reflecting the search of an increasing number of scholars into the anatomical, social, and artistic influences of Vesalius and his opus magnum book "De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem" on 16th century and later scientific evolution.”

This book focuses on some of these anatomists, artists, publishers and other personalities, who in different ways remained in the shadow’ of Vesalius.

This is most pertinent in the case of Vesalius’s collaborator and artist Jan Steven van Calcar, whom Vesalius only mentioned as ‘his friend’, but was probably responsible for at least an important number of the plates and figures in the famous Fabrica and Epitome. This gradually gains momentum enhanced by a recently found drawing (figure 1) which is commented on in the book by Caiati and co-workers, and is believed to be a preliminary sketch by Jan Steven van Calcar of one of the most iconic drawings in the Fabrica, namely the so-called ‘Philosopher’. (see image)

It is in this light that I would like to take a few people out of the shadows and bring them into the spotlight, and by this, explaining how this book came about.

Click on the image for a larger version

I first was introduced to Bob Van Hee in 2006 by Ann Van de Velde. Professor Robrecht H. Van Hee who is a surgeon and medical historian, with over 160 publications to his name, has always had a special interest in Andreas Vesalius. In 2005 he promoted Vesalius for a television contest programme about “Who’s the most famous Belgian in history”.

In 2007 Ann and I were organizing the AEIMS conference “Confronting Mortality with Art and Science”. This conference brought together a group of artists, scientists and medical illustrators.

Bob van Hee and anatomist Francis Van Glabbeek both gave excellent lectures on Vesalius, Triverius and Philip Verheyen during a nocturnal visit to the Plantin Moretus museum in Antwerp.

It was also at this conference I invited Joanna Ebenstein to give a talk on her then new project” The morbid anatomy library blog” which has grown into the amazing art /science platform it is today.

The conference was such a success that we decided to set up BIOMAB, Biological and Medical Art in Belgium, with a teaching programme ARSIC ( art researches science international collaborations) .

BIOMAB would never have seen the light of day if it wasn’t for the energy, and drive and fearless enterprising spirit of hematologist and medical artist; Dr. Ann Van de Velde. Over the years we have organized many dissection drawing workshops, exhibitions, conferences, made films and books and have written many articles and given many lectures. Our article in the book “Anatomical Drawing From Cadavers – Limb by Limb Removed -- Brought Us Together” elucidates our collaborations and our intension and achievements.

Anatomist and surgeon Professor Francis Van Glabbeek, founding member and currently President of BIOMAB, and a passionate collector of antiquarian medical books, has been a driving force in continuing Vesalius’s legacy by bringing artists together with scientists, and, in the spirit of Vesalius, teaching anatomy from direct observation. I remember the first meeting with Francis with much fondness. He lovingly showed me a first edition of the Fabrica and spoke with so much passion and knowledge about the work and influence that Vesalius and the Fabrica still have on anatomy today.

This article continues HERE

- Details

Clicking on this image will download a

PDF file with the book information

This is a new, as yet unpublished, book authored by several of my good friends who with me follow Vesaliana all over the world. There are too many of my friends to count, but I highly recommend this book. Dr. Miranda

In this richly illustrated book, a multitude of academic scholars present new findings concerning Andreas Vesalius Bruxellensis and his contemporaries. One of those discoveries includes a preparatory sketch by Jan Steven van Calcar for a drawing in Vesalius’ famous ‘Fabrica’, called ‘The Philosopher’.

Included are authentic letters, written by Vesalius to his friends Benedetto Varchi and Octavo Landi, are presented and translated for the first time and are thoroughly discussed, shedding new light on crucial periods of Vesalius’ life like his leave from academic Padua, exchanged for imperial service to Charles V, or his contribution in the treatment of Philips II’s son, crown prince Carlos in Spain.

Anatomical novelties, discovered by Vesalius’ friends and contemporaries, are equally broadly exposed, like Canani’s input in human arm musculature or Valverde’s ‘corrections’ of Vesalius’ Epitome. Valverde’s publication became one of the greatest ‘bestsellers’ in anatomy during the 16th and 17th century, thereby spreading the ‘Vesalian Revolution’ all over Europe. But also, the relationship between Vesalius and his Paduan room mate John Kay or Caius is explicated, as are a number of family descendants of Vesalius.

That Vesalius influenced artists in anatomical models and drawings is newly acknowledged in this book, as well as his influence on veterinary medicine.

In short, an inspiring new account of Vesalius’ extraordinary long-term influence on anatomy, science and art in general. One interesting point is that until now, many of the series of articles that composes the book where only available in Greek!

Jacqueline Vons (Emer. Professor of Latin and Medical History, University of Tours, France) comments "Centered around the figure of Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), this book ‘In the Shadow of Vesalius’ offers a vast panorama of the anatomical knowledge in Europe during early Modern times.

Some new documents and private letters have been discovered and are finely analyzed, as are anatomical books written by contemporaries and successors of Vesalius. The studies gathered here show how the text and iconography’s diffusion of De Humani Corporis Fabrica and Epitome made Vesalius the first modern medical authority (auctoritas): his work was quoted, copied, discussed by all those who were interested in the anatomy of the human body."

Click here to download a PDF file with a description of the book, the Table of Contents, and the information to pre-order this book which will be launched on November 14, 2020. To order a book at a pre-launch discounted price, you can go directly to the publisher's website (http://garant.be/shadow-of-vesalius/).

Pascale recently wrote an article looking back at how this book came to be. Here is the story of "The Long Road to the book "In the Shadow of Vesalius"