Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 847 guests online

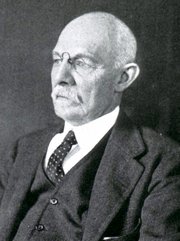

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

Clicking on this image will download a

PDF file with the book information

This is a new, as yet unpublished, book authored by several of my good friends who with me follow Vesaliana all over the world. There are too many of my friends to count, but I highly recommend this book. Dr. Miranda

In this richly illustrated book, a multitude of academic scholars present new findings concerning Andreas Vesalius Bruxellensis and his contemporaries. One of those discoveries includes a preparatory sketch by Jan Steven van Calcar for a drawing in Vesalius’ famous ‘Fabrica’, called ‘The Philosopher’.

Included are authentic letters, written by Vesalius to his friends Benedetto Varchi and Octavo Landi, are presented and translated for the first time and are thoroughly discussed, shedding new light on crucial periods of Vesalius’ life like his leave from academic Padua, exchanged for imperial service to Charles V, or his contribution in the treatment of Philips II’s son, crown prince Carlos in Spain.

Anatomical novelties, discovered by Vesalius’ friends and contemporaries, are equally broadly exposed, like Canani’s input in human arm musculature or Valverde’s ‘corrections’ of Vesalius’ Epitome. Valverde’s publication became one of the greatest ‘bestsellers’ in anatomy during the 16th and 17th century, thereby spreading the ‘Vesalian Revolution’ all over Europe. But also, the relationship between Vesalius and his Paduan room mate John Kay or Caius is explicated, as are a number of family descendants of Vesalius.

That Vesalius influenced artists in anatomical models and drawings is newly acknowledged in this book, as well as his influence on veterinary medicine.

In short, an inspiring new account of Vesalius’ extraordinary long-term influence on anatomy, science and art in general. One interesting point is that until now, many of the series of articles that composes the book where only available in Greek!

Jacqueline Vons (Emer. Professor of Latin and Medical History, University of Tours, France) comments "Centered around the figure of Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), this book ‘In the Shadow of Vesalius’ offers a vast panorama of the anatomical knowledge in Europe during early Modern times.

Some new documents and private letters have been discovered and are finely analyzed, as are anatomical books written by contemporaries and successors of Vesalius. The studies gathered here show how the text and iconography’s diffusion of De Humani Corporis Fabrica and Epitome made Vesalius the first modern medical authority (auctoritas): his work was quoted, copied, discussed by all those who were interested in the anatomy of the human body."

Click here to download a PDF file with a description of the book, the Table of Contents, and the information to pre-order this book which will be launched on November 14, 2020. To order a book at a pre-launch discounted price, you can go directly to the publisher's website (http://garant.be/shadow-of-vesalius/).

Pascale recently wrote an article looking back at how this book came to be. Here is the story of "The Long Road to the book "In the Shadow of Vesalius"

- Details

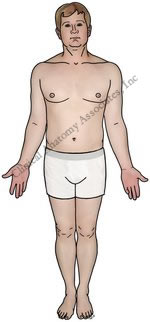

Anatomical position

UPDATED:The term [proximal], from the Latin [proximus] meaning "next" and its counterpart [distal], from the Latin [distans] meaning "distant", have been poorly defined and this causes misunderstanding in the proper use of these terms. This is particularly true in the medical industry.

The classical definition of [proximal] are "nearest, closer to the origin, closer to the point of reference" and also "closer to the beginning", or "opposite of distal". [Distal] is, of course, the opposite. All of these definitions are lacking a consensus between the participants in a conversation. This lack of proper definition could potentially lead to problems in an interventional situation and a patient could be injured.

In our lectures and training materials we use a working definition1 as follows:

“Proximal has two meanings:

1- Closer to the point of attachment, where one end of the attached structure is free, and

2- Closer to the point of origin of flow of a fluid”

Distal is of course, opposite to proximal.

In the first acception of the word, a clear example is the attachment of the upper and lower extremities. Moving away from the shoulder or the hip joint is a distal movement. “The wrist joint is distal to the elbow joint”. The same is true for the Fallopian (uterine) tube, where the proximal attachment of the tube is to the uterus and the free distal end of the tube is its fimbriated end.

In the second acception of the word, in any anatomical structure, organ, or system where there is flow of a fluid (food, urine, bile, blood, etc.) it is accepted that normal flow (antegrade flow) goes from proximal to distal and that abnormal flow (retrograde flow) goes from distal to proximal.

1. Use of this definition is permitted, as long as CAA, Inc. is credited, or a link to this article is posted with it.

Image property of: CAA.Inc. Artist: Victoria G. Ratcliffe

- Details

If you arrived to this website looking for information on Atrial Fibrillation, you will find some here and in this article.

Prevention of Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation;

Elimination of the Left Atrial Appendage.

An online educational video.

Randall, K. Wolf MD, FACS, FACC

This video educational program is hosted by the Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart and Vascular Center Education Center

Atrial fibrillation (AFib) is estimated to affect up to 4% of the population. Characterized by a rapid, irregular heartbeat, AFib is largely due to abnormal electrical impulses that cause the atria of the heart to quiver instead of beating steadily. Blood flow is reduced and is not completely pumped out of the two small upper chambers of the heart, the atria. This negatively impacts cardiac performance and also allows the blood to pool and potentially clot, especially in an extension of the left atrium, the left atrial appendage (LAA). At rest, a normal heart rate is approximately 60 – 100 beats per minute. In a person with AFib, that heart rate can increase to 180 bpm or even higher.

The main concern with AFib and stagnant blood flow in the LAA is the potential for clot formation (thrombus). While this can happen in either atria (right or left) the anatomy of the right atrium and right atrial appendage are less conducive to clot formation. The LAA is exactly the opposite and the clots, should they float into the bloodstream, tend to enter the larger arteries that go towards the head and brain, increasing the chances for a stroke.

In this educational video Dr. Wolf discusses the above, as well as the benefits of the elimination of the LAA, decreasing blood pressure, decreasing the chances of a stroke, and helping return the heart to normal rhythm.

Dr. Wolf is a surgical innovator who since the year 2000 has been a pioneer in the minimally invasive surgical treatment of AFib. He has performed over 2000 Wolf MiniMaze procedures since the first one in 2003 and has demonstrated the procedure to over 800 heart surgeons worldwide. He has been visiting professor in 18 countries, including Oxford University, University of Tokyo and Peking University. Dr. Wolf has delivered hundreds of invited lectures at hospitals, academic meetings and seminars in the United States and abroad.

Dr. Wolf is currently a member of the DeBakey Heart and Vascular Center at Houston Methodist Hospital in the Texas Medical Center. He serves as the arrhythmia specialist of the group. In 2018 Dr. Wolf operated on AF patients from 32 US states. He was also the keynote speaker at the annual Japanese Society for Tobacco Control in Takamatsu, Japan and the annual Chinese Society of Cardiothoracic Surgeons in Shenyang, China.

NOTE: Dr. Randall Wolf is a contributor to Clinical Anatomy Associates. My personal thanks to him and to the DeBakey Heart and Vascular Center for their invitation to participate in this and other educational videos. Dr. Miranda.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

William S. Halsted

mouseover for

Samuel J. Crowe

In my many years working with medical industry, surgeons, and surgery, I have heard many times that such and such surgical technique follows “Halsted’s Rules of Surgery”. The problem is that only two of these “rules” were mentioned and never did I receive an answer while working with Ethicon and Ethicon Endosurgery, and never did I receive an answer as to where could I find the reference regarding the other rules, if they even existed.

I recently read a great 1957 book by Samuel James Crowe, MD (1883-1952), titled “Halsted of John Hopkins; the man and his men”. Dr. Crowe lived for one year with Dr. William Stewart Halsted (1852-1922) and his wife as a medical student at John Hopkins. He was also an intern for Dr. Harvey Cushing, and although he wanted to follow Cushing into neurosurgery, Dr. Halsted placed him in charge of the newly created department of otolaryngology at John Hopkins, a position he did not want. Dr. Crowe went on to become a world-wide renown otolaryngologist.

Here are Halsted’s “Rules of Surgery” as explained by Dr. Crowe, based on Halsted’s research, experiments, and observations (with my own notes and comments):

1. Wounds are resistant to infection when no bits of tissue have been:

a. torn with clamps

b. torn by the rough handling of retractors

c. devitalized by hastily and carelessly applied ligatures

Note: this follows the ancient rule of “Primum Non Nocere”: first and foremost, do not harm

2. Wounds or parts rich in blood vessels usually heal without any visible granulation, even when no antiseptic precautions have been taken.

3. Incisions should be closed carefully and gently, layer by layer

4. The approximating sutures should never put the tissues under tension, since tension interferes with the blood supply and may cause necrosis

Note: Tension-avoidance surgical techniques follow this, one of the prime rules of surgery.

5. The end of the forceps used to pick up bleeding points should be small, to avoid crushing and destroying the vitality of surrounding tissues

Note: This observation led to the creation of fine, multiple toothed thumb forceps used today in cardiovascular surgery , such as the Cooley, DeBakey, Castaneda, etc. type forceps.

6. A drain is essential when there is necrotic tissue and infection

7. Silk should never be used in the presence of infection

Note: This makes sense. Since silk is an organic material, infected tissues will react to the presence of this extraneous material causing more inflammation, and the phagocytic cells in the tissues will destroy the silk and its capacity to hold the tissues together

8. The silk (suture) employed should never be coarser (larger gauge) than necessary and it is well to employ a suture a thread that is not stronger that the tissue it holds

9. A greater number of fine stitches is better than a few coarse ones

Note: This also makes sense. Halsted was known to be extremely meticulous and he could place a hundred stitches of fine silk thread where other surgeons would place a lesser number of coarser stitches. Using a larger number of fine stitches distributes the approximating tension of the sutures over a larger area, thus reducing the chance for suture dehiscence.

10. Avoid when possible the combined use of silk and catgut in a wound

11. For sewing up an abdominal wound, when it is necessary to take heavy deep stitches perforating skin and muscles, silver wire serves admirably

Note: Remember the times when these guiding principles where laid. Nylon, polypropylene, and other synthetic absorbable and non-absorbable sutures had yet to be discovered. Today the same dictum would probably say “For sewing up an abdominal wound, when it is necessary to take heavy deep stitches perforating skin and muscles, a synthetic non-absorbable suture material serves admirably”

It must be noted that Halsted never called the above the “rules of surgery”, rather they are observations that have become guiding principles. These have influenced the world of surgery to this day.

SIDE NOTE: It has been said many times that Dr. Halsted was the first to use rubber gloves. This is not true, Dr. Crowe says that “it was an evolution rather than a happy thought” and it involved his wife Caroline Hampton. This will be the subject of another article.

- Details

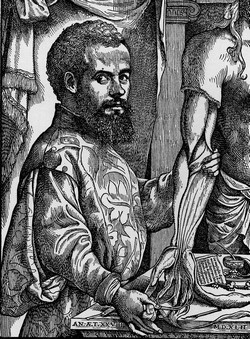

Figure 1: Vesalius Fabrica Portrait

Recently I acquired the 1925 book “The Iconography of Andreas Vesalius” by Marion Harry Spielmann (1858-1948). M.H. Spielmann was a well-published Victorian art scholar and critic. At the end of this article you can find the bibliographical information on this book.

The book is a serious detailed research of the known paintings, lithographies, sculptures, and medals that show the likeness of Andreas Vesalius, the date of publication and the author’s commentary on each one.

Andreas Vesalius is known as the “Father of Modern Anatomy”. He pushed for a description of the structure of the human body as seen in a dissection, going against the trend at the time where the anatomy was that described by Galen of Pergamon in his books. Galen’s anatomy was based on animal dissection and not a lot of human dissection. Furthermore, the lecturer would read from the book and the demonstrator pointing at the structures ignoring the discrepancies between the book and the body. For additional information and images click here.

Vesalius opus magnum (great work) was the publication in May 1543 of one of the most famous books in medical history. The title of the book is “De Humani Corporis Fabrica, Libri Septem” (Seven Books on the Structure of the Human Body). The book is now known as the “Fabrica”. This has led numerous artists to paint his likeness, many times based on past images or sometimes from pure imagination. The latest modern edition of the Fabrica was published in 2014.

We do know of only one portrait that depicts Vesalius’ likeness at the time of printing (1542) and that is the second image in the Fabrica of 1543 (figure 1) This image was carved in a pear wood block later used for printing. The woodblock indicates the date of carving (1542) and the age of the great anatomist that year (28). The sketch from which the block of wood was carved is most surely made by Jan Stephan Van Calcar (1449-1546). There is only supposition as to who was the artist that carved the woodblock, and there are several research papers on the subject. The best suggestion is that the woodcarvers were Francesco Marcolini (1505-1560) and Domenico Campagnola (1500-1564), both mentioned in a paper by Jaffe and Buchanan (2016). Campagnola is actually thought to be the woodcarver for the title page of the 1543 Fabrica.

The Iconography book goes into great detail on this image of the great anatomist, and dedicates a detailed description of the title page of the 1543 and the 1555 editions of the Fabrica, descriptions that I can only encourage to be read by researchers interested in the life and works of Andreas Vesalius. The book can be read online the Internet Archive here. The book is written mostly in English, but has an introduction in French.

Figure 2: 1555 Fabrica Title Page

“The Iconography of Andreas Vesalius” is a rare book, it is not easy to find, and probably the most important characteristic of the book is not mentioned in the many descriptions of the book found on the Internet, medical libraries, and antiquarian booksellers websites: The book originally included a separate, folded-in-four, high-quality linen paper print of the title page of the 1555 Fabrica. Most of the books found today have lost this print. Figure 2 shows a scan of the print found in the book I acquired. A 4.5 Mb watermarked actual size of this print can be seen here. If you want to download it, you can right click on the image and then click on "Save As".

This reprint of the Fabrica’s title page was done using the 1555 original woodblock, which makes it priceless. As shown in the accompanying image, the page leaves blank the two places where the title of the book and the dedication to the king and printer markings where placed. These would have been prepared in separate type and rearranged for a different use after printing. The print measures 16 7/8 by 12 1/4 inches (31.1 by 42.9 cms) The woodblock of the title page of the 1555 Fabrica was last used in 1934 when it was used to print the 1934 edition of the Icones Anatomicae, and then returned to the Louvain University in Belgium where it was destroyed by the German army in 1940. The Icones Anatomicae was the last print using the original woodblocks.

The rest of the original woodblocks was burned during a WWII bomb raid on July 16, 1944.

The following information is from the Stanford Library and it is one of the few that indicate the existence of the reprint of the 1555 Fabrica title page in an envelope pasted on the book cover reverse.

Author/Creator: Spielmann, M. H. (Marion Harry), 1858-1948.

Subject: Vesalius, Andreas, 1514-1564. History of Medicine. Physicians. 1500s

Genre: Biographical Information. Historical Works. Portraits

Bibliographic information:

Date: 1925

Series: Research studies in medical history ; no. 3, 1925

Note: Includes index. Title-page of De humani corporis fabrica libri septum by Andreas Vesalius, Second edition, 1555 printed direct from the original wood block in the pocket on verso of cover.

Personal Note: I am working on updating my library catalog to reflect the latest book acquisitions and gifts received. Dr. Miranda.

Sources:

1. “The Iconography of Andreas Vesalius” M.H. Spielmann. The Wellcome Historical Medical Museum London. John Bale, Sons & Danielson Ltd.

2. “The Andreas Vesalius Woodblocks: A Four Hundred Year Journey from Creation to Destruction” Acta Med Hist Adriat 2016; 14(2);347-372

3. "The identity of the artists involved in Vesalius Fabrica 1543” Guerra, F. (1969) Medical History, 13(1), 37.

- Details

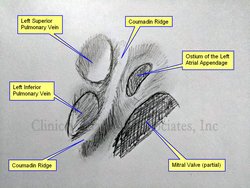

Coumadin ridge

Click on the image for a larger version

UPDATED: The [Coumadin ridge], also known as the [Warfarin ridge], or a [left atrial pseudotumor]. is an excessive elevation or protrusion of a normal ridge found between the left superior pulmonary vein and the internal ostium of the left atrial appendage. Usually this ridge will extend inferiorly towards and anterior to the ostium of the left inferior pulmonary vein. The Coumadin ridge is considered an anatomical variation of the otherwise small ridge, known as the left lateral ridge.

Because of its location and morphology, some cardiologists and radiologists have mistaken this elevation or fold of the internal anatomy of the left atrium for a thrombus and prescribed anticoagulant therapy (Coumadin or Warfarin) when none was needed, hence its name.

To understand the generation of the Coumadin ridge we must understand the embryology of this area of the heart. The left atrial appendage is the original left atrium in the embryo, which is displaced anteriorly and superolaterally when the veins that enter the atrium start to dilate at their distal end creating the left sinus venarum. After the left atrium proper has formed, the left atrial appendage is left as nothing more than an embryological remnant that can cause problems if the patient has atrial fibrillation (AFib). The ridge forms at the point where the left atrial appendage and the sinus venarum meet.

The Coumadin ridge can vary in morphology, from presenting as an elevated ridge, to a bulbous, pedunculated mass that seems to float within the left atrial appendage and undulate, following the cardiac motion, forcing the cardiologist into believing they are in the presence of a thrombus or a tumor within the heart.

This fold of tissue may contain the ligament of Marshall, autonomic nerves, and a small artery. In rare cases there may be an actual tumor arising from the location of the Coumadin ridge, but this is just a coincidence.

Now that the Coumadin ridge is a better known anatomical variation, cardiologist sometimes refer to their finding as a pseudotumor, a description that may scare the patient, but is only but a fold of tissue inside the heart.

Finding a Coumadin ridge in a patient with atrial fibrillation can be an interesting situation requiring differential diagnosis, as a patient with AFib can present with thrombi in the left atrial appendage. What to do? Is it or is it not a thrombus? Also, a differential diagnosis is needed in the case where the image is actually that of a left atrial tumor or an atrial myxoma.

The accompanying image is own work based on Sra (2004) and McKay (2008), and is a graphite on paper sketch. The image shown an internal view of the left atrium showing the left superior and inferior pulmonary vein, the ostium of the left atrial appendage and a segment of the area of the mitral valve.

We would like to thank Dr. Randall K Wolf, a contributor to Medical Terminology Daily for suggesting this article.

Sources:

1. “Coumadin ridge: An incidental finding of a left atrial pseudotumor on transthoracic echocardiography” Lohdi,AM, et al. World J Clin Cases. 2015 Sep 16; 3(9): 831–834

2. “Coumadin ridge” Tasco, V. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/coumadin-ridge

3. “Papillary fibroelastoma arising from the coumadin ridge” Malik, M, Shilo, K, Kilic,A. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2017;9(2):118-120.

4. “‘Coumadin ridge’ in the left atrium demonstrated on three dimensional transthoracic echocardiography” McKay,T., Thomas, L. Europ J Echocard (2008) 9, 298–300

5. “Endocardial imaging of the left atrium in patients with atrial fibrillation” Sra J; Krum D; Okerlund D; Thompson H. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2004 Feb; Vol. 15 (2), pp. 247