Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 1426 guests online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

From the movie "Short Circuit" (1986):

Howard Marner: "Crosby, we're going to have to ask you to surrender the robot"

Newton Crosby: "Stat?"

Howard Marner: "Stat!"

Newton Crosby: "What does that mean, anyway?"

Howard Marner: "I don't know. But that's not the point"

The medical term [stat] arises from the Latin [statim] which means "immediately". By use and later abbreviation it has become [stat] with the same meaning. The term has somehow become overused in movie and television medical dramas with many people not knowing its meaning or etymology.

Note: The links to Google Translate include an icon that will allow you to hear the Greek or Latin pronunciation of the word.

- Details

UPDATED: This is a medical word that originates from Greek roots. The word [pathos] meaning "disease", and the word [γνωμο] (gnomos) or [gnomonikos] meaning "opinion", "judge" or "someone fit to judge". The word [pathognomonic] refers to a symptom, a sign, or a combination that, by its presence, defines or diagnoses a specific pathology or condition.

Most pathognomonic diagnoses are attained by a combination of symptoms and signs. Single pathognomonic events are not common. An example would be the presence of Koplik's spots in the buccal mucosa close to the exit of the parotid duct which are pathognomonic for measles. Koplik's spots (named after Dr. Henry Koplik) are small white spots with a reddish background. In addition to this location, Koplik's spots can be found occasionally on the conjunctiva, vaginal mucosa, or gastrointestinal mucosa1.

Sources:

1. Steichen, O., & Dautheville, S. (2009). Koplik spots in early measles. Can Med Assoc J 180 (5), 583

2. Koplik H. The diagnosis of the invasion of measles from a study of the exanthema as it appears on the buccal mucous membrane. Arch Pediatr 1896;13:918-22.

3. "Despedir al Sarampion" Article in Spanish by Dr. Luis Vasta.

- Details

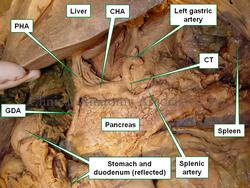

The [proper hepatic artery], also known as the [hepatic artery proper] is the continuation of the common hepatic artery after the branching of the gastroduodenal artery. The proper hepatic artery is between 1.5 to 2.3 cm in length and close to 5mm in diameter.

It ascends superiorly, anterior to the portal vein and to the left of the common bile duct and hepatic duct. These three structures, arterial, venous, and bliliary, form the portal triad. The portal triad is found between the two layers of the lesser omentum.

The proper hepatic artery ends when it bifurcates giving origin to the left and right hepatic arteries.For more information on anatomical variations of the celiac trunk and the proper hepatic artery click here.

The image shows an anteroinferior view of the liver and stomach, the duodenum and stomach are reflected anteriorly. CT= Celiac trunk, CHA= Common hepatic artery, PHA= Proper hepatic artery, GDA= Gastroduodenal artery

Sources:

1. "Gray's Anatomy"38th British Ed. Churchill Livingstone 1995

2. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

3. "Variations of hepatic artery: anatomical study on cadavers" Sebben, GA et al Rev. Col. Bras. Cir. 40:3 May/June 2013

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

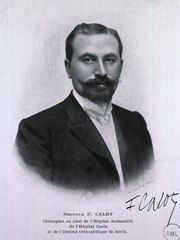

Jean-Francois Calot (1861 – 1944)

Jean-Francois Calot (1861 – 1944). French physician and anatomist, Jean-Francois Calot was born in Arrens-Marsous, a small farming community of the Hautes-Pyrénées. He received his bachelor degree in 1880 at Saint-Pe de Bigorre, and then continued to study Medicine at the University of Paris, where he worked as an anatomy prosector. His doctoral thesis “De La Cholecystectomie” (On Cholecystectomy) was published in 1890 and republished in 1891.

Although his main interest laid in orthopedics and tuberculosis, Calot’s name is eponymically tied to an anatomical landmark described in his thesis, the “Triangle of Calot”, a triangular area that includes the biliary ducts associated with the gallbladder and the vascular supply to the gallbladder. This is an important region because of the high number of anatomical variations found in the area.

There is a discrepancy between the original description of this triangular region by Calot and what is used today. For more information, click on this link to read more on the “Triangle of Calot”, also known as the “cystohepatic triangle”.

During his medical career Calot worked at several French hospitals including the Rothschild hospital where he became Chief of Surgery. He was also the Chief of Surgery for the Cazin-Perrochaud Hospital, and the Orthopedic Institute of Berck-sur-Mer

Dr. Jean-Francois Calot and

the treatment of Pott's disease

During his orthopedic career Calot published many books “Chirurgie et orthopédie de guerre”, “Les maladies qu'on soigne á Berck”, “Berck et ses traitements : les raisons de sa supériorit?”, but his opus magnus is the book “« L'orthopédie indispensable aux praticiens” (Indispensable orthopedics for practitioners).

Calot is also known for his treatment of tuberculotic abscesses, and a conservative approach to musculoskeletal tuberculosis. The surgical approach of the times was to surgically open and clean the tuberculotic bone. Calot is known to have said “Ouvrir la tuberculose, c'est ouvrir la porte d' la mort” (To open the tuberculosis is to open the door to death).

Continuing his studies and treatment of tuberculosis, on December 22nd, 1896 Calot presents the the French Academy of Medicine a study of the treatment of 37 patients with hyperkyphosis due to Pott’s disease, a tuberculotic spinal deformity, named after Sir Percival Pott. This method included traction and a brace. The second image shows this treatment. Dr. Calot is standing at the center, looking at the patient.

In 1900 Calot founded the “Orthopedic Institute of Berck” which today is known as “Calot’s Institute of Berck-sur-Mer”.

Sources:

1. “Calot's triangle” Abdalla S, Pierre S, Ellis H. Clin Anat. 2013 May;26 (4):493-501

2. “La Vie et l'OEuvre de Francois Calot, chirurgien orthopédiste de Berck” Loisel, P. (in French). Report presented at Société Francaise d'Histoire de la Médecine on 18 March 1987

Image 1: Original image courtesy of the National Library of Medicine

Image 2: Original image public domain courtesy of the Universite Paris-Descartes Histoire de la Santé

- Details

UPDATED: This is a word based on the Greek term[νευρών] (nev?r??n), which was used initially to denote or mean "sinew" or "tendon". The early descriptions of anatomy made no difference between a nerve and a tendon. The meaning of the word [aponeurosis], although not exactly literal, is that of a "flat tendon".

This is important in abdominal wall anatomy and to understand the anatomy of the inguinofemoral region as it relates to hernia. There are three aponeuroses (plural form), the external oblique aponeurosis, the internal oblique aponeurosis, and the transversus abdominis aponeurosis, all contributing to the rectus sheath and the linea alba.

There are other aponeuroses in the human body, such as the fascia lata and the superficial and deep gastrocnemius aponeuroses that end in the calcaneal (Achilles) tendon.

- Details

The [common hepatic artery] is one of the three branches that arise from the celiac trunk providing blood supply to the liver, duodenum, and pancreas. The common hepatic artery ends where the gastroduodenal artery arises, and then changes its name to proper hepatic artery

It is a relatively short artery, close to 3 cm. in length, with an average diameter of 7 mm.

It can present with simple to complex anatomical variations. In one of them the common hepatic artery arises from the superior mesenteric artery and not from the celiac trunk. For more information on anatomical variations of the celiac trunk and the common hepatic artery click here.

The image shows an anteroinferior view of the liver and stomach, the duodenum and stomach are reflected anteriorly. CT= Celiac trunk, CHA= Common hepatic artery, PHA= Proper hepatic artery, GDA= Gastroduodenal artery

Sources:

1. "Gray's Anatomy"38th British Ed. Churchill Livingstone 1995

2. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

3. "Variations of hepatic artery: anatomical study on cadavers" Sebben, GA et al Rev. Col. Bras. Cir. 40:3 May/June 2013

Image property of: CAA.Inc.Photographer: David M. Klein