Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 1527 guests online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Pioneers of Surgical Stapling

If you look at a desktop stapler, you will see that it is formed by very simple components: a staple, a pushing element, and an anvil that helps form the staple. This simple device has revolutionized surgery allowing surgeons to perform complex anastomoses and resections that otherwise could take a long time using sutures.

The story of surgical stapling starts with surgeons that established the parameters for a safe and leak-proof anastomosis as well as the tenets of antisepsis.

Christian Albert Theodor Billroth (1829 – 1894) set the parameters for gastrointestinal anastomoses when he developed the “Billroth I” and “Billroth II” procedures.

William S. Halsted (1852 – 1922), who started modern American medical education, set the “rules” for a good anastomosis and tissue management. Halsted preached for the use of small-gage sutures and needles, good surgical technique, and reduction of tissue trauma. Halsted proved empirically that a single-layered anastomotic suture worked as well as a double-layered suture line. Surgical staplers apply a single layer of staples.

In 1910 Halsted developed a non-suture anastomotic device, but it never went beyond the prototype stage.

The search for a safe end-to-end anastomosis led to the development of the “Murphy button” by Dr. John Benjamin Murphy (1857 – 1916) a “sutureless compression anastomotic device” in 1982, the precursor of some modern compression anastomotic devices, such as those developed by Novo GI (ex NiTi Surgical).

Continued....

The history of surgical stapling [1] ; [2]; [3]; [Video]

Sources

1. "Surgical stapling" Mallina, R F 1962 Scientific American 207, 48

2. “Science of Stapling: Urban Legend and Fact” Pfiedler & Ethicon EndoSurgery

3. “Cholecystointestinal, gastrointestinal, enterintestinal anastomosis, and approximation without sutures” Murphy JB. Med Rec (1892) 42: 665

4. “Study of Tissue Compression Processes in Suturing Devices” Astafiev, G. (1967 (USSR Ministry of Health, Ed.)

5. “Rese?as Hist?ricas: John Benjamin Murphy” Parquet, R.A. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam 2010;40:97.

6. “The Science of Stapling and Leaks” Baker, R. S., & et al. (2004) Obesity Surgery, 14, 1290-1298.

7. “John Benjamin Murphy – Pioneer of gastrointestinal anastomosis”Bhattacharya, K., & Bhattacharya, N. (2008). Indian J. Surg., 70, 330-333.

8. “The Story of Surgery” Graham, H. (1939) New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co.. Inc.

9. “Compression Anastomosis: History and Clinical Considerations”Kaidar-Person, O, et al, e. (2008) Am J Surg, 818-826.

10. “Current Practice of Surgical Stapling”Ravitch, M. M., Steichen, F. M., & Welter, R. (1991) Philadelphia: Lea& Febiger.

11. “Aladar Petz (1888-1956) and his world-renowned invention: The gastric stapler” Olah, A. Dig Surg 2002: 19; 393-3

- Details

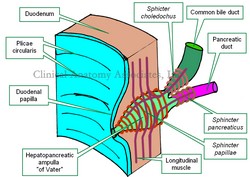

The [hepatopancreatic ampulla] or "ampulla of Vater" is a dilation found at the conjunction and common end of the common bile duct (ductus choledocus) and pancreatic duct (ductus pancreaticus). The presence of the hepatopancreatic ampulla creates a nipple-like elevation of the duodenal mucosa called the "duodenal papilla

The term [ampulla] is Latin and refers to a rounded and globular-shaped flask, which perfectly describes this structure. The hepatopancreatic ampulla was first described by Abraham Vater (1684 - 1751).

The hepatopancreatic ampulla is surrounded by a complex sphincteric mechanism, the "Sphincter of Oddi".

The ampulla of Vater is situated in the "choledochal window" an area of the duodenum devoid of musculature through which the hepatopancreatic ampulla / sphincter of Oddi complex passes. It is also complex in its interior. It usually presents an incomplete septum in its interior that separates the flow of pancreatic juice and bile at least for part of its trajectory.

In one of the known anatomical variations, this septum can be complete, having in fact a double-barreled ampulla that empties bile and pancreatic juice separately into the lumen of the second portion of the duodenum.

Image property of CAA. Inc. Artist: Dr. E. Miranda

- Details

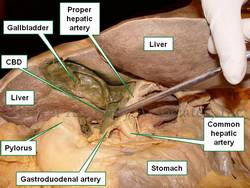

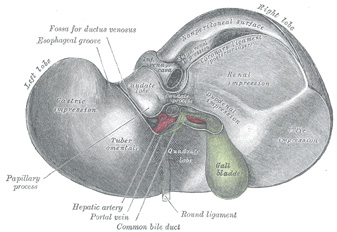

UPDATED: The [common bile duct] also known as the [ductus choledocus]. is part of the hepatobiliary tree, taking bile from the gallbladder and liver to the second portion of the duodenum. The common bile duct begins at the junction of the common hepatic duct with the cystic duct, it continues inferiorly, usually to the right of the proper hepatic artery and anterior to the portal vein. It then passes posterior to the first portion of the duodenum, is surrounded by pancreatic tissue and ends at the hepatopancreatic ampulla of (Vater).

The junction of the common bile duct with the hepatopancreatic ampulla of (Vater) is the narrowest portion of the hepatobiliary tree, The lodging of a gallstone at this junction can be the cause for choledocholitiasis and jaundice.

In the accompanying image the common bile duct is elevated with a probe. The lesser omentum has been removed to show the common bile duct and vascular structures that are found between the two peritoneal layers that form the lesser omentum.

- Details

The [gallbladder] is a bile transient storage organ, part of the hepatobiliary tree, situated in the anteroinferior aspect of the liver. The gallbladder is found in a depression on the inferior aspect of the right lobe of the liver, the gallbladder fossa or fossa vesicae felleae.

In the gallbladder we describe its dome-shaped fundus, the body of the organ, and the neck which is the area that opens into the cystic duct. Close to the neck, the gallbladder has a small pouch (Hartmann's pouch) which is important for surgeons during a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, as this is where they will lock one of the instruments that allows them to manipulate the gallbladder for dissection of the organ from the gallbladder fossa (the gallbladder bed). The other surgical grasper is placed at the gallbladder fundus.

The gallbladder is composed by three layers. From deep to superficial they are:

• Mucosa: Characterized by a columnar epithelium. Towards the neck of the gallbladder the mucosa creates spiral ridges that continue in to the cystic duct.

• Fibromuscular layer: This layer is composed by connective tissue and smooth muscle, mostly longitudinal

• Serosa: This is an incomplete layer and is formed by visceral peritoneum covering the area of the gallbladder not in contact with the liver. In an unusual anatomical variation, the serosa layer can be almost complete, forming a pseudomesentery that may contains some veins.

The gallbladder receives its blood supply by way of the cystic artery, a branch of the right hepatic artery. The venous return is by way of multiple small veins that empty into the liver venous system. In some cases, these veins may form large sinuses between the liver and the gallbladder causing potential troublesome bleeding during a cholecystectomy. For those who like medical history, Dr. Eric Muhe performed the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy on September 12, 1985! We are but a few days from the 30th anniversary!

For more information on terminology on "gall-", "bile", "chol", and "chole", click here.

Sources:

1 "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

2. "Anatomy of the Human Body" Henry Gray 1918. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger

Image modified by CAA, Inc. Original image courtesy of bartleby.com

- Details

Last Friday April 17, I prepared and delivered a lecture on "Surgical Sutures, Needles, and Knots" which included a hands-on workshop on knots and wound closure on simulated tissue.

This was presented at the invitation of the Pre-Health club of the Mount Saint Joseph University in Cincinnati, OH. I am always glad to be invited to do these presentations as they allow me to maintain contact with the future generation of Health Care Professionals.

Of course this is a very short presentation compared to the longer course that Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. delivers for medical companies, but it shows these future professionals the complexity of the world of wound closure, healing, surgical sutures, needles, and knots.

We ended the lab with the challenge to do a two-layer closure of a simulated wound. Most of the attendees did a pretty good job. Congratulations!

My personal thanks to Dr. Eric Johnson who coordinated the meeting, and to the Pre-Health Club for their invitation. For more pictures of the meeting, see the Facebook album page of "Medical Terminology Daily"

- Details

The cystic duct is a tubular structure that connects the neck of the gallbladder to the extrahepatic ductal system. It is 2-4 cm. in length and its lumen is about 2.6 +/- 0.7 mmm. The shape of the cystic duct varies, as it can be straight, angled, or acutely curved.

The mucosa of the cystic duct presents with 2-10 crescent-shaped folds that create a spiral-shaped inner structure referred to as the "Valve of Heister", first described by Lorenz Heister in 1732. These folds become smaller and scarcer towards the distal portion of the duct.

The cystic duct can present with several anatomical variations, from total absence where the neck of the gallbladder empties directly in to the common bile duct, to duplication, and even rare occasions where the cystic duct empties separately into the duodenal lumen.

The cystic duct is an important surgical landmark as it is one of the boundaries of the cystohepatic triangle or "Triangle of Calot", described by Jean-Francois Calot (1861 - 1944), which determines the location of the cystic artery, a critical structure that needs to be ligated and transected during a cholecystectomy.

Sources:

1 "Cystic Duct and Heister’s “Valves” Dasgupta,C, Stringer, MD, Clin Anat (2005) 18:81–87

2. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

3. "Anatomy of the Human Body" Henry Gray 1918. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger

Image modified by CAA, Inc. Original image courtesy of bartleby.com