Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 1403 guests online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

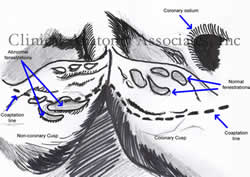

UPDATED: The root term for this word comes from the Latin [fenestram] meaning "window". [Fenestration] is "the presence or the act of creating a window". As an example, the term is used to describe a small, round opening found in the medial wall of the tympanic cavity (middle ear), the [fenestra cochleae] or [fenestra rotunda] meaning "round window" (see image 1).

Fenestrations can be found as natural occurrences in the body, as a result of an infection or destructive process or pathology, or they can be surgical procedures attempting to create a window, opening, or foramen. The cusps of all the heart valves can present normal fenestrations in the distal aspect of the cusp, beyond the coaptation or closure line. These become abnormal fenestrations when they occur below the coaptation line which may need to be repaired. Image 2 shows normal and abnormal fenestrations in the cusps of an aortic valve. Fenestrations in a valve cusp can be caused by endocarditis, among other causes.

Some surgical fenestrations that can be described are:

1. Fenestration of a tooth, allowing for drainage.

2. Pericardial fenestration, also known as a "pericardial window" to allow for drainage of excessive pericardial fluid (pericardial effusion).

3. Fenestration in a Fontan procedure, where a small opening or "window" is created to relieve excessive pressure in the venous circulation.

Word suggested by: J.Estrada

Original image #1courtesy of bartleby.com. Image#2 property of CAA, Inc.Artist: Dr. Miranda

- Details

This medical term [hypoacusia] is composed of the prefix [ hyp-], a derivate from the Greek [υπό] (ip? which means "under", "deficient" or "below". The root term [-acus-] is also a derivate from the Greek [ακούω] (ako?o?) meaning “listen”, or “hear”. The adjectival suffix [-ia] has a double meaning of “pertaining to” and “condition”. The term hypoacusia means then “a condition of deficient hearing”. It can also be used as [hypoacusis] with the same meaning.

A common mistake is to use this term for total deafness. This is not correct, in [hypoacusia] the patient has varying degrees of hearing loss, but there is some hearing function left.

There are many causes of hypoacusia: genetic, viral, bacterial, traumatic, etc. There are two types of hypoacusia. The first one is transmission hypoacusia, where the mechanical system that transmits vibration from the external ear and tympanic membrane (eardrum) to the inner ear can be damaged. The second type is neurosensory hypoacusia, where the components of the inner ear as well as the nerve structures of the vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII cranial nerve) up to and including brain areas related to the hearing process may be damaged.

Different degrees of hypoacusia have been demonstrated to affect proper communication functions and learning. Lower levels of hypoacusia (less than 25%) can be undiagnosed in small children; in fact, there are several studies that prove that the presence of low level hypoacusia in small children is a good predictor of language alteration and learning problems if not diagnosed properly and timely.

My personal thanks to Maria E. Gallegos, Chair of the Speech Pathology School, Iberoamerican University, Santiago Chile, for her help in this article. Dr. Miranda

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

The development of the series of articles on The history of surgical stapling [1] ; [2]; [3] was started because of personal communications with the family of the late Drs. Mark and Michael Ravitch.

This lead me to research on the biographies of the pioneers of surgery, anesthesia, and asepsis, as well as the life of those who invented, developed, and lead the way in the use of these now-widely-used surgical devices.

The most common question I received from the general public was "What are these surgical staplers and how are they used?". The following video answers these questions as well as the history of the development of surgical staplers. I sincerely hope that this video is well received by the Medical Industry and the public in general.

My personal thanks to the family of the late Drs. Mark and Michael Ravitch for their support, to the Museum of Surgical Staplers for images and links, and to the Covidien Surgical Products Division (today Medtronic Stapling) for providing the surgical staplers shown in this video. Dr. Miranda

This video was initially published in 2014, and directed by David M. Klein, Creative Director of Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc.

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Surgical staplers through history

In the mid 1900’s the Soviet Ministry of Health established in Moscow the Scientific Research Institute for Experimental Surgical Apparatus and Instruments. This was forced by the need to train surgeons to perform complex operations at long distances from the capital cities. The Institute developed an incredible array of instruments including single line, linear cutter, and circular staplers which had applications such as gastrointestinal stapling, bone staplers, skin staplers, cornea and vascular staplers. etc. One of the problems of these instruments was that since they were hand-made, the parts from different staplers were not necessarily interchangeable.

The Moscow Thoracic Surgical Institute had very good results with the bronchial stapler, and it was here that in 1958, almost by chance, Dr. Mark M. Ravitch (1910 – 1989) and three other American physicians had the opportunity to evaluate patients that had been operated with this instrument, as well as seeing it in use.

Again, totally by chance, Dr. Ravitch happened to find a store that carried this instrument and as he tells “…quite unnecessarily I am sure, I identified myself plainly as an American. The only instrument they had in stock that day was the bronchial stapler…” He brought the instrument to the Thoracic Institute where the personnel calibrated it. This instrument came back to the USA with him to start a revolution in surgery.

Back in the USA, Dr. Ravitch started research with this and other instruments he procured in later trips. He recruited Dr. Felicien Steichen (1926 – 2011) to work with him, starting a friendship and collaboration that would last until his death. Both Drs. Ravitch and Steichen helped perfect and develop the modern instruments we use today: The linear stapler, the linear cutter, and the circular stapler.

Once these instruments were introduced, the development and advancement of the technology was pioneered by medical industry in the USA. First with Mr. Leon Hirsch, founder of the U.S. Surgical Corporation (today Covidien Surgical Devices), and later by Johnson and Johnson’s Ethicon Endo-Surgery (today Ethicon). These companies developed first the reloadable reusable surgical staplers and later the disposable reloadable surgical staplers.

Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) was common with gynecologist, but not used by general surgeons. Dr. Erich Muhe (1938 – 2005) was the first to perform a laparoscopic cholecystectomy in 1985, followed by many others. With the advent of MIS, these companies launched the development of laparoscopic surgical staplers, quite common today.

What about the future? First is the development of newer stapling technologies that take into account the viscoelastic behavior of tissues under rapid compression, multiple height staple lines, microstaplers, etc. Then, the advent of NOTES (Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery) needs the development of smaller and smaller surgical staplers that can be used through a natural orifice and delivered through a flexible endoscope. That is, for now, the new frontier of surgical stapling.

The history of surgical stapling [1] ; [2]; [3]; [Video]

Sources

1. "Surgical stapling" Mallina, R F 1962 Scientific American 207, 48

2. “Science of Stapling: Urban Legend and Fact” Pfiedler & Ethicon EndoSurgery

3. “Cholecystointestinal, gastrointestinal, enterintestinal anastomosis, and approximation without sutures” Murphy JB. Med Rec (1892) 42: 665

4. “Study of Tissue Compression Processes in Suturing Devices” Astafiev, G. (1967 (USSR Ministry of Health, Ed.)

5. “Rese?as Hist?ricas: John Benjamin Murphy” Parquet, R.A. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam 2010;40:97br />6. “The Science of Stapling and Leaks” Baker, R. S., & et al. (2004) Obesity Surgery, 14, 1290-1298.

7. “John Benjamin Murphy – Pioneer of gastrointestinal anastomosis”Bhattacharya, K., & Bhattacharya, N. (2008). Indian J. Surg., 70, 330-333.

8. “The Story of Surgery” Graham, H. (1939) New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co.. Inc.

9. “Compression Anastomosis: History and Clinical Considerations”Kaidar-Person, O, et al, e. (2008) Am J Surg, 818-826.

10. “Current Practice of Surgical Stapling”Ravitch, M. M., Steichen, F. M., & Welter, R. (1991) Philadelphia: Lea& Febiger.

11. “Aladar Petz (1888-1956) and his world-renowned invention: The gastric stapler” Olah, A. Dig Surg 2002: 19; 393-399

NOTE: The copyright notice for the images in this article can be found in the series "The History of Surgical Stapling" in this website

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Pioneers of Surgical Stapling

Before the invention of the first surgical staplers some inroads where towards the development of automated suture devices and clamps that allowed surgeons to manipulate the tissues to obtain proper suture placement. These devices, some of them based on the first sewing machines did not survive the test of time.

The first true and successful surgical stapler was developed in 1908 by Dr. Hümer Hültl (1868 – 1940) in Hungary. Although heavy and cumbersome, this stapler had some of the concepts that are found today in modern surgical staplers: “B" shaped staples, staggered rows of staples, and attention to the avoidance of leakage through the staple line. Hültl’s stapler placed four staggered rows of wire staples. Today’s surgical staplers usually place two or three staggered rows of surgical titanium staples. History tells us that Dr. Hültl sold only 50 of his instruments because of high price, difficulty in reloading, and most importantly, the reticence of surgeons to adapt to this new technology.

In 1920 the Hültl stapler was improved by Dr. Aladar Petz (1888 – 1956), also Hungarian. The “Von Petz stapler” was lighter, easier to use, used silver staples, more affordable in price, and sold all over the world, allowing for surgeons to see this new technology in use.

Unfortunately, the Von Petz stapler could only be used once in surgery, as it needed to be cleaned, reloaded, and sterilized before reusing it. 1934 Dr. H Friedrich of Ulm Germany invented the replaceable cartridge, so that a surgical stapler could be reused multiple times in one surgery. This opened the way for a “triangular” type end-to-end anastomosis that until this time could not be performed. Also, Dr. Friedrich’s stapler had adjustable tissue compression.

Personal note: In 1987 I had the opportunity to scrub in one of the last uses of a Von Petz stapler in surgery (Chile, South America). This instrument was used to perform an “in toto” stapling and transection of the pulmonary hilum for a pneumonectomy. The instrument, after almost 40 years of its development, performed flawlessly. Dr. Miranda

Continued...

The history of surgical stapling [1] ; [2]; [3]; [Video]

Sources

1. "Surgical stapling" Mallina, R F 1962 Scientific American 207, 48

2. “Science of Stapling: Urban Legend and Fact” Pfiedler & Ethicon EndoSurgery

3. “Cholecystointestinal, gastrointestinal, enterintestinal anastomosis, and approximation without sutures” Murphy JB. Med Rec (1892) 42: 665

4. “Study of Tissue Compression Processes in Suturing Devices” Astafiev, G. (1967 (USSR Ministry of Health, Ed.)

5. “Rese?as Hist?ricas: John Benjamin Murphy” Parquet, R.A. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam 2010;40:97

6. “The Science of Stapling and Leaks” Baker, R. S., & et al. (2004) Obesity Surgery, 14, 1290-1298.

7. “John Benjamin Murphy – Pioneer of gastrointestinal anastomosis”Bhattacharya, K., & Bhattacharya, N. (2008). Indian J. Surg., 70, 330-333.

8. “The Story of Surgery” Graham, H. (1939) New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co.. Inc.

9. “Compression Anastomosis: History and Clinical Considerations”Kaidar-Person, O, et al, e. (2008) Am J Surg, 818-826.

10. “Current Practice of Surgical Stapling”Ravitch, M. M., Steichen, F. M., & Welter, R. (1991) Philadelphia: Lea& Febiger.

11. “Aladar Petz (1888-1956) and his world-renowned invention: The gastric stapler” Olah, A. Dig Surg 2002: 19; 393-399

I

I I

I