Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 622 guests online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

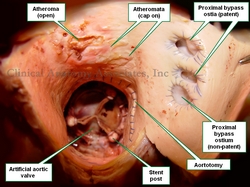

The medical word [atheroma], has the root term [-ather-] arising from the Greek [ath?ra] meaning "gruel", "porridge", or "groats". This refers to the consistency of the content of a soft atheromatous plaque. The suffix [-oma] means "mass", "growth" or "tumor". A mass of soft gruel-like substance. The plural form for atheroma is [atheromata].

An atheroma is abnormal edema and accumulation of cholesterol and fatty acids with varying amount s of macrophages, fibroblasts and connective tissue in the tunica intima of an artery. It is usually covered by a “cap” of thicker, drier, yellowish fibrous material. An atheroma is a cavity filled with a fatty gruel-like material covered by a cap. Atheromatous disease is characterized by a large number of these masses in the walls of the arteries of a patient.

Atheromata are found in smaller caliber arteries can reduce the lumen of the artery leading to ischemia and in the case of the coronary arteries, myocardial infarction.

The cap in an atheroma can be dislodged by the arterial blood flow in which case the content of the atheroma is emptied into the bloodstream becoming a fatty embolus. Since arteries become arterioles and then capillaries, this fatty embolus will flow distally to the point where it will lodge, blocking blood flow.

WARNING: The image of the pathology in this article is quite descriptive

The accompanying image is a clear depiction of this situation. This is a superior view of the ascending aorta. The patient in this case had an artificial aortic valve implanted and the aortotomy performed for the procedure is also indicated. The patient also had three coronary bypass grafts, one of which was clogged or non-patent. There are at least two atheromata with the cap still on. The image also shows at least one atheroma empty. This indicates that the content of the atheroma became a fatty embolus. Click on the image for a larger depiction.

Image property of: Photographer: David M. Klein

- Details

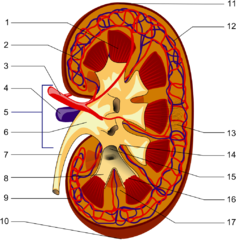

The word [calyx] is Latin, meaning "an outer covering", although it's origin is most probably Greek, from [kylix], meaning "a cup". This is the meaning we use today in medical terminology. The plural form for [calyx] is either [calyces] or [calyxes].

In human anatomy the term is used to denote small, cup-like extensions of the renal pelvis that help collect urine.

Each one of the minor calyces (8-20) surrounds extensions of the renal parenchyma called renal papillae. These papillae are found at the apex of the renal pyramids. This allows the urine to drip into the minor calyx as though into a cup. The minor calyces will then converge into larger calyces, each one known as a major calyx. There are between 2 to 4 major calyces in each kidney.

The major calyces then join together to form the renal pelvis, which continues with the ipsilateral ureter to the urinary bladder.

Sources

1. "Gray's Anatomy"38th British Ed. Churchill Livingstone 1995

3. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

Images in the public domain, courtesy of Wikipedia

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

J. Marion Sims

J. Marion Sims (1813 – 1883). American surgeon and gynecologist. James Marion Sims is considered the “Father of Gynecology". He was born in Hanging Rock, South Carolina. At age 12 he moved to Lancaster, South Carolina. Sims studied at the SC College and later moved to Philadelphia, PA where he studied Medicine at the Jefferson Medical College, graduating in 1835. He returned to Lancaster to practice, but shortly after moved to Montgomery, Alabama.

In 1845 Sims started his studies to close vesicovaginal fistulas, operating in the same patient many times. He was finally able to do this using a lateral recumbent position (later called Sims’ position) and a specially designed, U-shaped, vaginal retractor (later called Sims’ speculum). For this procedure he used silver wire as suture material. His findings were published in 1852 in his paper entitled “On the Treatment of Vesico-Vaginal Fistula”

After moving to New York J. Marion Sims helped in the founding and establishing the Woman's Hospital in the State of New York in 1855. Sims moved to Europe during the American Civil War. In Europe he became well-known and in 1866 published his book “Clinical Notes on Uterine Surgery”. While in Paris Sims performed the first cholecystostomy to relieve a blocked gallbladder.

He continued his contribution to gynecology advancing uterine prolapse surgery, advocating hysterectomy for bleeding fibroids, and suggested total hysterectomy as the only means of curing uterine cancer. One of his last contributions (not well accepted initially) was the indication for immediate exploratory laparotomy in abdominal gunshot wounds, burst ectopic pregnancy and any other sharp abdominopelvic trauma.

Sims died in New York on November 13, 1883

Sims’s life was and still is the cause of controversy. His use of slave patients, his professional jealousy and egotism, and his more than once reported disdain for patient privacy would not be accepted by today’s standards. Today in Lancaster his name helps the community thorough the “J. Marion Sims Foundation” dedicated to “support prevention and educational programs that help the citizens of Lancaster and the communities of Great Falls and Fort Lawn”

Sources:

1. “The Influence of J. Marion Sims on Gynecology” Heaton CE Bull N Y Acad Med 1956 32 (9): 685–688

2. “J. Marion Sims, the Father of Gynecology: Hero or Villain?” Sartin, JS South Med J 2004;97(5):500-505

3. “J. Marion Sims: A Defense of the Father of Gynecology” O’Leary JP South Med J 2004;97(5):427-429

4. “Carl Langenbuch and the First Cholecystectomy” Traverso LW Am J Surg 1976; 132; 81-82

- Details

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

The Latin word [caput] means "head" and the word [medusae] is also Latin and means "Medusa's". [Caput medusae] means "Medusa's head". Medusa is a Greek mythological figure, ruler of the Gorgons; in her mortal form she had a head covered with snakes and looking into her eyes would cause an observer to turn into a stone statue. She was killed by Perseus who used a shield to see her reflection without turning to stone and was thus able to cut her head off.

The term [caput medusae] is used in medical terminology to denote a medical sign, a crown of engorged veins that radiate from the umbilicus. These engorged veins are caused by increased hepatic portal pressure (portal hypoertension) which causes retrograde flow in the veins from the abdominal cavity to the superficial cutaneous veins, engorging them.

The caput medusae sign is usually seen in patients with advanced hepatic cirrhosis.

WARNING: The following explicit images show different stages of this sign. Each of the following links will open images in separate screens and web sites: Image 1; Image 2; Image 3; Image 4.

Medusa's head image in the public domain courtesy of Wikipedia. All other images are the property of each website. We only provide the links to them.

- Details

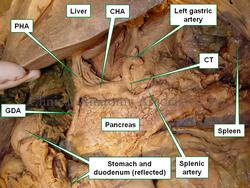

The [splenic artery], also known as the [lienal artery] is one of the branches of the celiac trunk, the first unpaired branch of the abdominal aorta. Through its branches the splenic artery provides arterial blood supply to the stomach, pancreas, and spleen.

From its origin at the celiac trunk, the splenic artery goes to the left and then curves posteriorly around the spinal column. It has a very tortuous shape. In 1571 Julius Arantius (1530 -1589) described it as "tortuous, in the manner of a snake". A study by Sylvester et al (1998) measured the uncoiled (straight) lenght of the splenic artery (5.8 - 11.3 cm) as well as the variation in coiling (tortuosity) of the artery.

The splenic artery has several branches:

- Pancreatic arteries: Several small perforating branches. The largest of them, usually the first perforator is called either the "middle pancreatic artery", the "great pancreatic artery", or the "arteria pancratica magna"

- Left gastroepiploic artery: The largest of the splenic artery branches, this artery forms part of the greater curvature vascular arcade and provides blood supply to the left side of the stomach and part of the greater omentum

- Short gastric arteries: These are several short branches that course within the gastrosplenic ligament the connects the spleen to the greater curvature and fundus of the stomach. Take down of these branches is critical in certain procedures for esophageal hiatus hernia

- Splenic branches: The terminal branches of the splenic artery supply the spleen. It usually divides into a superior and an inferior branch, each one giving up to four branches that enter through the hilum of the spleen

Although rare, the splenic artery can be the site for an aneurysm. It is the third most common abdominal aneurysm, after abdominal aorta and iliac artery aneurysms. They are being diagnosed more frequently now as incidental findings in cross-sectional imaging.

Sources:

1. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

2. "Tortuosity of the Human Splenic Artery" Sylvester, PA, Stewart R, Ellis, H. Clin Anat (1996):8:214-218

3. "Splenic artery aneurysms"Trastek VF, et al. Surgery (1982) 91:694-699

9. "Splenic Artery Aneurysms and Pseudoaneurysms: Clinical Distinctions and CT Appearances" Agrawal, GA. Johnson, PT. Fishman EK. Am J Roentg (2007) 188: 4; 992-999

- Details

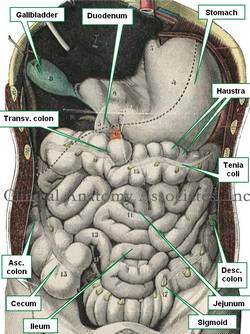

The term [tenia coli] is Latin and refers to three longitudinal whitish bands of tissue seen on the surface of the colon. An alternate spelling for this term is [taenia coli].

The word [tenia] is Latin are means "ribbon" or "tape". It is a term used to describe tapeworms. [Coli] is also Latin and means "pertaining to the colon". See accompanying image. Click the image for a larger depiction.

The tenia coli are formed by the gathering or grouping of the longitudinal (external) muscle layer found in the components of the digestive system. While in most of the organs the longitudinal layer is spread out around the organ, in the colon the grouping of the fibers form these three longitudinal bands. The contant tonic contraction of these bands of muscle cause the colonic wall to bunch forming sacculations known as "haustra".

The tenia coli of the cecum converge at the base of the vermiform appendix. This is one anatomical constant used by surgeons to localize and identify the vermiform appendix.

There are three tenia coli best seen in the transverse colon. Because of their relationship with the omentum and the transverse mesocolon, two of them are known as the [tenia omentalis] and the [tenia mesocolica] respectively. The third one is free, and is the easiest one to observe; it is called the "free tenia" or [tenia libera].

The tenia are well formed until the distal portion of the sigmoid colon. When it forms part of the rectosigmoid region all three tenia start to dissipate and spread out until they form the longitudinal layer of the rectum.

Since the small intestine is not necessarily always small in relation to the colon (because of food content, intestinal gases, or pathology), the location of the organ and the presence of haustra, as well as the presence of tenia coli and appendices epiploica, is used to recognize the organ as colon.

Sources:

1. "Dorlands's Illustrated Medical Dictionary" 26th Ed. W.B. Saunders 1994

2. "The origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, AH, 1970

3. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

Image modified from the original from Testut and Latajet, 1931