Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 764 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

The prefix [retro-] has a Latin origin and means "posterior", "backwards", or "behind". The main use of this prefix in human anatomy and surgery is "posterior".

Applications of this prefix include:

- retroesternal: posterior to the sternum, such as the heart or the internal thoracic vessels

- retropharyngeal: posterior to the pharynx, as in the "retropharyngeal space", a potential space found posterior to the pharynx

- retroperitoneal: posterior to the peritoneum, referring to abdominal organs found outside and posterior to the peritoneal sac, such as the aorta and kidneys

- retrogastric: posterior to the stomach, as in the "retrogastric space", an area also known as the "lesser bursa"

- retroversion: a posterior rotation or turn. Usually refers to the posterior rotation of the uterus or a joint

- Details

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

François Poupart (1661-1709). Physician, zoologist, entomologist, and anatomist, Francois Poupart was born in Le Mans, France. His origins were very humble and he studied Medicine in Paris as a very poor student. He had great interest in entomology, studying the anatomy of insects. Poupart obtained his MD a the University of Reims and was a surgeon at the H?tel (hospital) Dieu. A naturalist, Poupart is known for having written a monograph on the anatomy of the leech.

His life is mostly unknown. Poupart died at the age of 48. His name is eponymically associated with the inguinal ligament, which he described in detail in 1705. Although this structure was originally described by Gabrielle Fallopius, it was Poupart who stated the function of the inguinal ligament as an attachment for the three lateral muscles of the abdominal wall.

*: There is no known image of Francois Poupart that we could find. If you have any source, please let us know through our "Contact Us" form.

Sources:

1. "Two eponymous surgeons: Cowper and Poupart" Ellis, H. Brit J Hosp Med 2009 701:4 225

2. "The Anatomical History of the Leech" Poupart, F. Phil Transact 1697 19:722-726

- Details

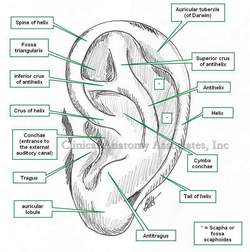

The word [pinna] is Latin and means "feather". It also means "wing". The variation [penna] as in the case of [pennate], means "winged". It refer to the external ear, or auricle. It appears that the use of the term [pinna] for ear arises from the ear-like or winged extensions of Viking and medieval helmets.

The ear has three components, the internal, middle, and external ear. The external ear is composed of the external acoustic canal and the pinna. The pinna is composed of fibrocartilage covered with skin, and has several ligaments and small muscles related to it. These muscles are extrinsic (between the pinna and the skull) and intrinsic (within the pinna) All these muscles have limited capabilities in the human.

The pinna receives blood supply from the anterior and posterior auricular arteries, and a small branch of the occipital artery. The nerve supply is by way of the great auricular nerve, the auricular branch of the vagus nerve, the auriculotemporal branch of the mandibular nerve, and the lesser occipital nerve.

The external (lateral) anatomy of the pinna is complicated and very detailed, with potential anatomical variations. Click on the image for a higher detail. The medial aspect of the pinna presents elevations which correspond to the depressions (fossae) on its lateral surface and they are named, eminentia conchae, eminentia triangularis, eminentia scaphoides, etc.

Image property of: CAA, Inc. Artist: Dr. Miranda

- Details

The prefix [circum-] is Latin and means "around" or "about". It is used in medical terms such as:

- Circumcision: the root term [-cis-] meaning to "cut". To cut around

- Circumflex: the root term [flex] for [flexion] meaning to "bend". Bends around, as in "circumflex artery"

- Circumambulation: a patient that walks in circles

Also in everyday terms such as:

- Circumlocution: to talk around a subject

- Circumnavigation: To sail or navigate around

- Circumscribe: to write in circles or around a subject

- Details

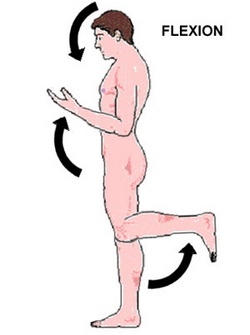

The word [flexion] comes from the Latin [flexere] meaning "to bend". In anatomy, flexion is the reduction in the angle between two bodily components that are communicated by a type of joint.

By contrast, [extension] refers to the opposite action, that is, the increase in the angle between two bodily components that are communicated by a type of joint.

The image shows flexion of the head, the upper extremity, and the lower extremity. Hover over the image to see extension of the same structures.

Excessive flexion (hyperflexion) or extension (hyperextension) of a joint can lead to potential pathology as would be the case of hyperextension of the neck as a result of a car crash (whiplash injury)

Note that in a human in the anatomical position, flexion of the upper extremity is an anterior movement, while flexion of the lower extremity is a posterior movement. You could make a case that in these image the upper extremity is performing an anteflexion (anterior flexion) while the lower extremity is performing a retroflexion (posterior flexion).

In the upper and lower extremities there are whole groups of muscles that, because of their action, are called flexors or extensors.

- Details

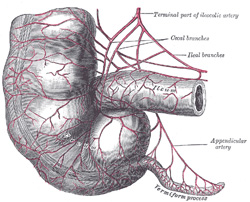

Terminal ileum, cecum,

and vermiform appendix

The word [vermis] is Latin and means "worm". The term [vermiform appendix] means "the worm-shaped appendage", and refers to a worm-like appendage that is related to the cecum, a segment of the right colon.

This structure was first described by Jacobo Berengario da Carpi in 1524, and it was Andreas Vesalius who first described it as an appendix, and suggested it looked like a worm. It has been called the [vermix] and the [cecal appendix]

The vermiform appendix* has the same four layers found in most of the abdominal digestive tract and is attached to the cecum at the point where the three tenia coli (libera, mesenterica, and omentalis) meet. The length of the vermiform appendix is variable. On average about 2.5 to 3 inches, it can be as long as 10 inches in length, with one recorded case of a 13 inch appendix!**

The location of the vermiform appendix is also subject to anatomical variation, being found in a retrocecal position in 65% of the cases. For more information on this organ's anatomical variations, click here.

The vermiform appendix is an intraperitoneal structure, as it has a peritoneal extension called the mesoappendix. Within the mesoappendix are the appendiceal arteries and veins. The appendiceal artery is usually a branch of the ileocolic artery.

Sources:

1. "The Origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, HA 1970 Hafner Publishing Co.

2. "Medical Meanings - A Glossary of Word Origins" Haubrich, WD. ACP Philadelphia

3 "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

4. "Anatomy of the Human Body" Henry Gray 1918. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger Image modified by CAA, Inc. Original image by Henry Vandyke Carter, MD., courtesy of bartleby.com

*. It is not proper to call this structure the "appendix", as there are many appendices in the human body.

**. Personal note: The longest vermiform appendix I have personally seen was 8 inches (20.3 cm) in length, retrocolic, and the tip of the organ was actually retrohepatic!. Dr. Miranda.